To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Tissot’s Illustrations for Renée Mauperin (1884).” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2020/05/15/tissots-illustrations-for-renee-mauperin-1884/. <Date viewed>.

Renée Mauperin, a novel by brothers Jules and Edmond de Goncourt, initially was published in 1864, then in several other editions, before surviving brother Edmond discussed illustrations for a new edition with James Tissot in late May 1882, in Paris. At the time, Tissot was living in London with young Kathleen Newton, who had moved into his St. John’s Wood home around 1876.

Kathleen, declining from tuberculosis, would model for the novel’s tragic heroine, who in the last third of the story suffered from debilitating heart disease. Some of Tissot’s illustrations were based on photographs of Kathleen, and he posed for some of the male figures. Her son Cecil Newton appears in one of the etchings, along with girls who may have been his sister, Violet, and Kathleen’s sister’s daughters, Belle and Lilian.

Edmond de Goncourt (c. 1877), by Nadar. (Wiki)

Kathleen Newton died of tuberculosis on November 9, 1882, at age 28, with her sister, Polly Hervey, at her side (according to the death register). Tissot draped the coffin in purple velvet and prayed beside it for hours. Immediately after the funeral on November 14, at the Church of Our Lady in Lisson Grove, St. John’s Wood, Tissot returned to Paris. On the morning of November 15, he called on Edmond de Goncourt, who noted in his journal that the artist was “very affected by the death of the English Mauperin.”

Renée Mauperin, illustrated with ten etchings by James Tissot, was published in 1884 in Paris by Charpentier.

In 1888, the English edition, published by Vizetelly, contained a prefatory note by Émile Zola:

“For many people…this is Messieurs de Goncourt’s masterpiece. The authors’ object has been to depict a phase of contemporary middle-class life. Their heroine, Renée, the most prominent personage of the story, is a strange girl, half a boy, who has been brought up in the chaste ignorance of virgins..Spoilt by her father, she has grown upon the dunghill of advanced civilization with an artistic soul and a nervous, refined temperament. She is the most adorable little thing imaginable, she talks slang, she paints and acts, her mind is awake to every form of curiosity, and she is possessed of masculine pride, straightforwardness, and honesty.”

However, due to an action she takes, her brother, Henri, is killed in a duel, and “Renée, horrified by what she has done, slowly dies of heart disease, her distressing agony lasting through nearly one-third of the volume.”

Below, excerpts from the novel accompany each etching, providing the story in brief. I have used The Project Gutenberg eBook, Renée Mauperin, by Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, et al., Translated by Alys Hallard (1902).

RENÉE MAUPERIN: RENÉE AND REVERCHON SWIMMING IN THE SEINE (FRONTISPIECE), by James Tissot. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Open Access.

I

“You would soon find out what a bore it is to be always proper. We are allowed to dance, but do you imagine that we can talk to our partner? We may say ‘Yes,’ ‘No,’ ‘No,’ ‘Yes,’ and that’s all! We must always keep to monosyllables, as that is considered proper. You see how delightful our existence is. And for everything it is just the same. If we want to be very proper we have to act like simpletons; and for my part I cannot do it. Then we are supposed to stop and prattle to persons of our own sex. And if we go off and leave them and are seen talking to men instead – oh, well, I’ve had lectures enough from mamma about that!”

This was said in an arm of the Seine just between Briche and the Île Saint Denis. The girl and the young man who were conversing were in the water. They had been swimming until they were tired, and now, carried along by the current, they had caught hold of a rope which was fastened to one of the large boats stationed along the banks of the island.

“Ah, now this, for instance,” she continued, “cannot be at all proper – to be swimming here with you.”

Renee Mauperin: Renee Hugging her Father as She Comes in to Breakfast (Beraldi 54)

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 14.1 x 10 cm (5 9/16 x 3 15/16 in.) sheet: 19.1 x 16 cm. (7 1/2 x 6 5/16 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-250 a. Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

IX

“Well!” exclaimed Renée, entering the dining-room at eleven o’clock, breathless like a child who had been running, “I thought every one would be down. Where is mamma?”

“Gone to Paris – shopping,” answered M. Mauperin.

“Good-morning, papa!” And instead of taking her seat Renée went across to her father and putting her arms round his neck began to kiss him.

“There, there, that’s enough – you silly child!” said M. Mauperin, smiling as he endeavoured to free himself.

And Renée, standing up after kissing him once more, moved back from her father, still holding his head between her hands. They gazed at each other lovingly and earnestly, looking into one another’s eyes. The French window was open and the light, the scents and the various noises from the garden penetrated into the room.

RENÉE MAUPERIN: DENOISEL READING IN THE GARDEN, RENÉE APPROACHING, by James Tissot. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Open Access.

IX

Denoisel, left to himself, lighted a cigar, picked up a book and went out to one of the garden seats to read. He had been there about two hours when he saw Renée coming towards him. She had her hat on and her animated face shone with joy and a sort of serene excitement.

“Well, have you been out? Where have you come from?”

“Where have I come from?” repeated Renée, unfastening her hat. “Well, I’ll tell you, as you are my friend,” and she took her hat off and threw her head back with that pretty gesture women have for shaking their hair into place. “I’ve come from church, and if you want to know what I’ve been doing there, why, I’ve been asking God to let me die before papa.”

Renee Mauperin: Renee Sitting at the Piano, Crying

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 14.3 x 9.8 cm. (5 5/8 x 3 7/8 in.) sheet: 28.7 x 22.3 cm. (11 5/16 x 8 3/4 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-252 a

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

XXVII

Denoisel had left Renée at her piano, and had gone out into the garden. As he came back towards the house he was surprised to hear her playing something that was not the piece she was learning; then all at once the music broke off and all was silent. He went to the drawing-room, pushed the door open, and discovered Renée seated on the music-stool, her face buried in her hands, weeping bitterly.

“Renée, good heavens! What in the world is the matter?”

Two or three sobs prevented Renée’s answering at first, and then, wiping her eyes with the backs of her hands, as children do, she said in a voice choked with tears:

“It’s – it’s – too stupid. It’s this thing of Chopin’s, for his funeral, you know – his funeral mass, that he composed. Papa always tells me not to play it. As there was no one in the house to-day – I thought you were at the bottom of the garden – oh, I knew very well what would happen, but I wanted to make myself cry with it, and you see it has answered to my heart’s content. Isn’t it silly of me – and for me, too, when I’m naturally so fond of fun!”

Renee Mauperin: Denoisel and Henri Mauperin in the Latter’s Rooms (Beraldi 57)

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching; early state. Plate: 10.1 x 14 cm (4 x 5 1/2 in.) sheet: 21.5 x 28.8 cm (8 7/16 x 11 5/16 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-253 a

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

XXXIV

Denoisel was at Henri Mauperin’s. They were sitting by the fire talking and smoking. Suddenly they heard a noise and a discussion in the hall, and, almost at the same time, the room door was opened violently and a man entered abruptly, pushing aside the domestic who was trying to keep him back.

“M. Mauperin de Villacourt?” he demanded.

“That is my name, monsieur,” said Henri, rising.

“Well, my name is Boisjorand de Villacourt,” and with the back of his hand he gave Henri a blow which made his face bleed. Henri turned as white as the silk scarf he was wearing as a necktie and, with the blood trickling down his face, he bent forward to return the blow, and then, just as suddenly, drew himself up and stretched his hand out towards Denoisel, who stepped forward, folded his arms, and spoke in his calmest tone:

“I think I understand what you mean, sir,” he said; “you consider that there is a Villacourt too many. I think so too.”

The visitor was visibly embarrassed before the calmness of this man of the world. He took off his hat, which he had kept on his head hitherto, and began to stammer out a few words.

“Will you kindly leave your address with my servant?” said Henri, interrupting him; “I will send round to you to-morrow.”

RENÉE MAUPERIN: HENRI MAUPERIN WOUNDED AFTER THE DUEL WITH BOISJORAND DE VILLACOURT, by James Tissot. Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Open Access.

XXXVIII

M. de Villacourt took off his frock-coat, tore off his necktie, and threw them both some distance from him. His shirt was open at the neck, showing his strong, broad, hairy chest. The opponents were armed, and the seconds moved back and stood together on one side.

“Ready!” cried a voice.

At this word M. de Villacourt moved forward almost in a straight line. Henri kept quite still and allowed him to walk five paces. At the sixth he fired.

M. de Villacourt fell to the ground, and the witnesses watched him lay down his pistol and press his thumbs with all his strength on the double hole which the bullet had made on entering his body.

“Ah! I’m not done for – Ready, monsieur!” he called out in a loud voice to Henri, who, thinking all was over, was moving away.

M. de Villacourt picked up his pistol and proceeded to do his four remaining paces as far as the walking-stick, dragging himself along on his hands and knees and leaving a track of blood on the snow behind him. On arriving at the stick he rested his elbow on the ground and took aim slowly and steadily.

“Fire! Fire!” called out Dardouillet.

Henri, standing still and covering his face with his pistol, was waiting. He was pale, and there was a proud, haughty look about him. The shot was fired; he staggered a second, then fell flat, with his face on the ground and with outstretched arms, his twitching fingers grasping for a moment at the snow.

Renee Mauperin: Renee Fainting after Hearing of her Brother’s Death in the Duel

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 11 x 14.2 cm. (4 5/16 x 5 9/16 in.) sheet: 22.5 x 22.8 cm. (8 7/8 x 9 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-255 a

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

XL

Denoisel opened the drawing-room door and saw Renée, seated on an ottoman, sobbing, with her handkerchief up to her mouth.

“Renée,” he said, going to her and taking her hands in his, “some one killed him –”

Renée looked at him and then lowered her eyes.

“That man would never have known; he never read anything and he did not see any one; he lived like a regular wolf; he didn’t subscribe to the Moniteur, of course. Do you understand?”

“No,” stammered Renée, trembling all over.

“Well, it must have been an enemy who sent the paper to that man. Ah, you can’t understand such cowardly things; but that’s how it all came about, though. One of his seconds showed me the paper with the paragraph marked –”

Renée was standing up, her eyes wide open with terror; her lips moved and she opened her mouth to speak – to cry out: “I sent it!”

Then all at once she put her hand to her heart, as if she had just been wounded there, and fell down unconscious and rigid on the carpet.

Renee Mauperin: M. Mauperin Sitting in a Public Garden in Paris

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 14 x 9.7 cm. (5 1/2 x 3 13/16 in.) sheet: 19 x 15.7 cm. (7 1/2 x 6 3/16 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-256 a

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

XLIV

Sometimes, as though he were answering inquiries about his daughter, he would say aloud, “Oh, yes, she is very ill!” and it was as though the words he had uttered had been said by some one else at his side. Often a work-girl without any hat, a pretty young girl with a round waist, gay and healthy with the rude health of her class, would pass by him. He would cross the street that he might not see her again. He was furious just for a minute with all these people who passed him, with all these useless lives. They were not beloved as his daughter was, and there was no need for them to go on living. He went into one of the public gardens and sat down. A child put some of its little sand-pies on to the tails of his coat; other children getting bolder approached him with all the daring of sparrows. Presently, feeling slightly embarrassed, they left their little spades, stopped playing and stood round, looking shyly and sympathetically, like so many men and women in miniature, at this tall gentleman who was so sad. M. Mauperin rose and left the garden.

Renee Mauperin: Renee and Her Father Sitting in the Porch of the Church at Morimond

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 15.1 x 9.6 cm. (5 15/16 x 3 3/4 in.) sheet: 33.4 x 20.5 cm. (13 1/8 x 8 1/16 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-257 b

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

LI

There was a stone seat under the porch with a ray of sunshine falling on it.

“It’s warm here,” she said, laying her hand on the stone. “Put my shawl there so that I can sit down a little. I shall have the sun on my back—there.”

“Ah!” said Renée after a few moments, “we ought to have been made of something else. Why did God make us of flesh and blood? It’s frightful!”

Her eyes had fallen on some soil turned up in a corner of the cemetery, half hidden by two barrel-hoops crossed over each other and up which wild convolvulus was growing.

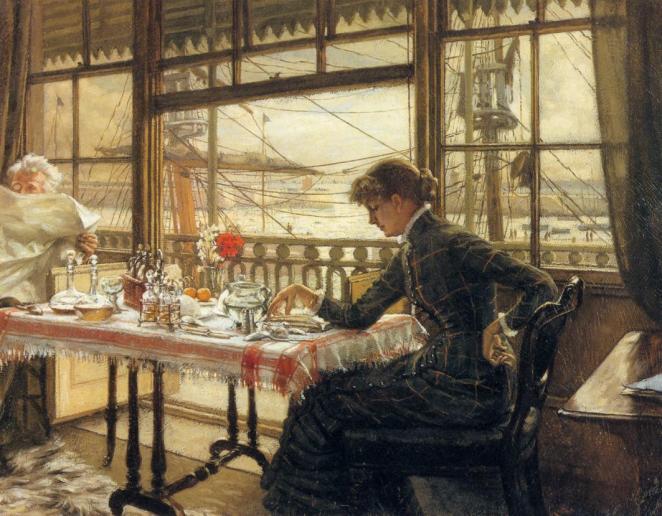

Renee Mauperin: M. and Mme. Mauperin in Egypt, 1882

James Tissot, French, 1836–1902

Etching. Plate: 10.7 x 14 cm. (4 3/16 x 5 1/2 in.) sheet: 21 x 33.2 cm. (8 1/4 x 13 1/16 in.)

Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr. x1944-258 b

Princeton University Art Museum, public domain for personal and educational use.

LXV

People who travel in far countries may have come across, in various cities or among old ruins – one year in Russia, another perhaps in Egypt – an elderly couple who seem to be always moving about, neither seeing nor even looking at anything. They are the Mauperins, the poor heart-broken father and mother, who are now quite alone in the world, Renée’s sister having died after the birth of her first child.

They sold all they possessed and set out to wander round the world. They no longer care for anything, and go about from one country to another, from one hotel to the next, with no interest whatever in life. They are like things which have been uprooted and flung to the four winds of heaven. They wander about like exiles on earth, rushing away from their tombs, but carrying their dead about with them everywhere, endeavouring to weary out their grief with the fatigue of railway journeys, dragging all that is left them of life to the very ends of the earth, in the hope of wearing it out and so finishing with it.

Related posts:

James Tissot’s Model and Muse, Kathleen Newton

Was Cecil Newton James Tissot’s son?

James Tissot’s garden idyll & Kathleen Newton’s death

© 2020 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

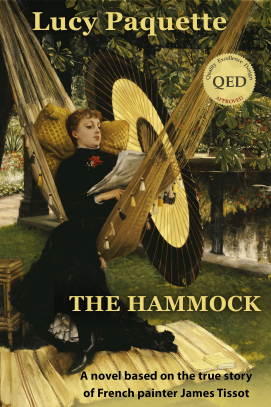

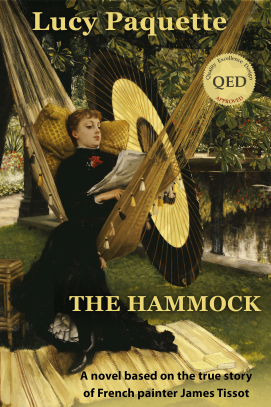

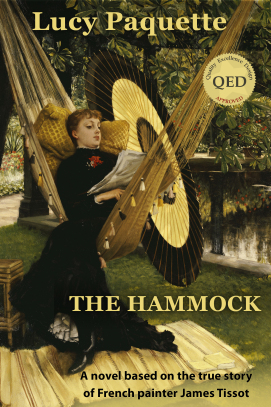

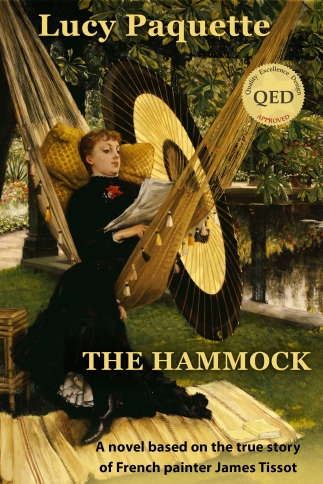

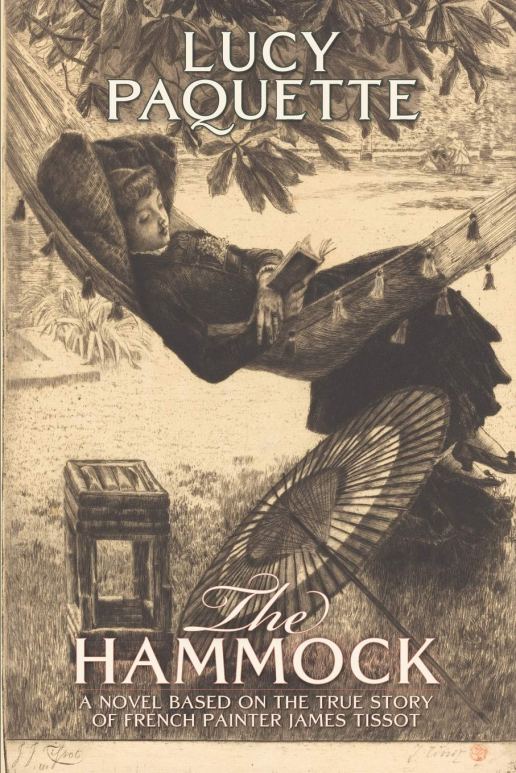

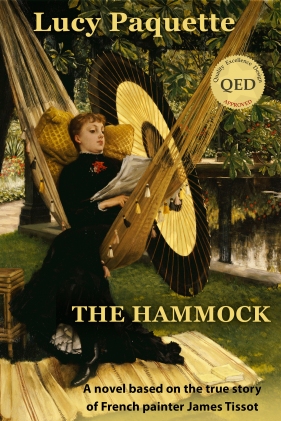

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

The setting for Seaside was the Royal Albion Hotel near the shore of Viking Bay in Ramsgate, Built in 1791, Albion House sits atop the East cliff, with a sweeping view of the beach and the Royal Harbour. Princess Victoria stayed in one of its elegant rooms, ornamented with Georgian and Regency cornices, iron balconies, and shutter-panelled windows, before she was crowned Queen

The setting for Seaside was the Royal Albion Hotel near the shore of Viking Bay in Ramsgate, Built in 1791, Albion House sits atop the East cliff, with a sweeping view of the beach and the Royal Harbour. Princess Victoria stayed in one of its elegant rooms, ornamented with Georgian and Regency cornices, iron balconies, and shutter-panelled windows, before she was crowned Queen

Richmond Bridge, built of Portland stone between 1774 and 1777, began as a toll bridge, but tolls ended in 1859. Its five segmental arches, rise gradually to the tall, 60-foot wide central span which allowed vessels to pass through the tallest arch.

Richmond Bridge, built of Portland stone between 1774 and 1777, began as a toll bridge, but tolls ended in 1859. Its five segmental arches, rise gradually to the tall, 60-foot wide central span which allowed vessels to pass through the tallest arch.

James Tissot was an individualist whose style and brushwork was neither entirely Academic, according to his training, nor always fashionable, though some of his oil paintings feature looser, more Impressionistic brush strokes. Though he did not establish trends, he absorbed them into his repertoire and transmuted them into a virtuoso formula all his own.

James Tissot was an individualist whose style and brushwork was neither entirely Academic, according to his training, nor always fashionable, though some of his oil paintings feature looser, more Impressionistic brush strokes. Though he did not establish trends, he absorbed them into his repertoire and transmuted them into a virtuoso formula all his own.

In

In

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in

b

b

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c  d

d

b

b  c

c

b

b  c

c

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.