To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot, the painter art critics love to hate.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2018/04/01/james-tissot-the-painter-art-critics-love-to-hate/. <Date viewed.>

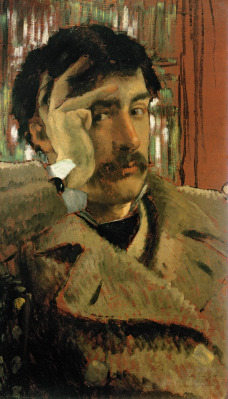

Self portrait (c.1865), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 49.8 by 30.2 cm (19 5/8 by 11 7/8 in.). The Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, California. Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection, 1961.16. Image courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot,” by Lucy Paquette © 2012.

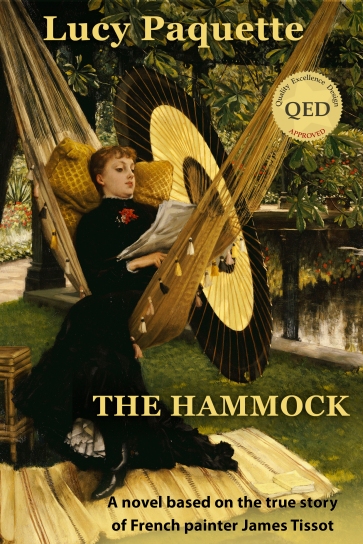

If you’re a regular reader, you know that both my blog and my book, The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, celebrate French painter James Tissot and his work. You also know that April 1 is my birthday, and that I write an annual April Fool’s Day post, so once again, here’s something a little different for you.

In the nine years that I’ve been researching Tissot, I’ve been startled and mystified by the nature of criticism of his work. I can tell you my least favorite of his paintings and why I don’t like them. But I find that Tissot’s critics – past and present – can’t seem to do only that. Their animosity toward Tissot has a bizarre personal thrust of resentment and spite, as if their dislike of his work is based on some grudge that ensued after a formerly tight friendship, along the lines of “I loved that man until he stole my girlfriend/was promoted over me at work/bought a Ferrari and wouldn’t let me test drive it.” And yes, these reviewers who love to hate James Tissot almost always happen to be male.

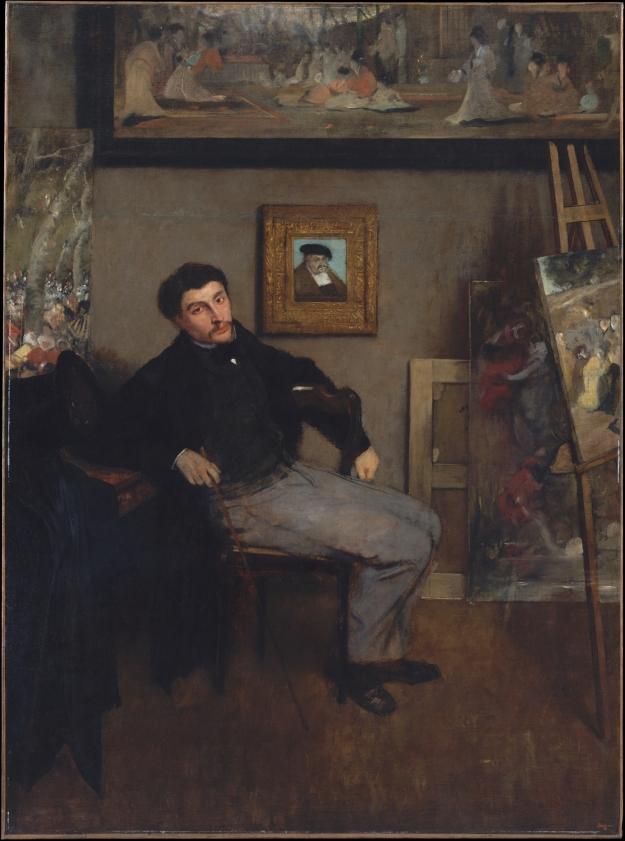

My introduction to the conflation of dislike of Tissot’s work with unhinged hatred of James Tissot himself was a 1985 review of a new Tissot biography published in advance of exhibitions of Tissot’s work in France and the U.S. The reviewer for The New York Times called his paintings “gloomy and inconclusive,” illustrating “boredom, tinged…with bitterness.” He continued, weirdly, “As for Tissot himself…Californians have access to him in the debonair but slightly shifty self-portrait that is in the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco…In short order, the devious, would-be jaunty little fellow who looks out at us from Degas’s portrait [at the Metropolitan Museum of Art] was making a fortune in Paris in his early 30’s [sic] and riding high in a fashionable townhouse.”

James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot (c. 1867-68), by Edgar Degas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

When the reviewer adds, “Unhindered by any personal commitment to anything in particular, he could take time off to see what the public wanted,” you might ask yourself, “So what’s so offensive about a successful single guy in his 30s?” According to this reviewer: “But what matters in the end is to get rich with good paintings and not with bad ones.”

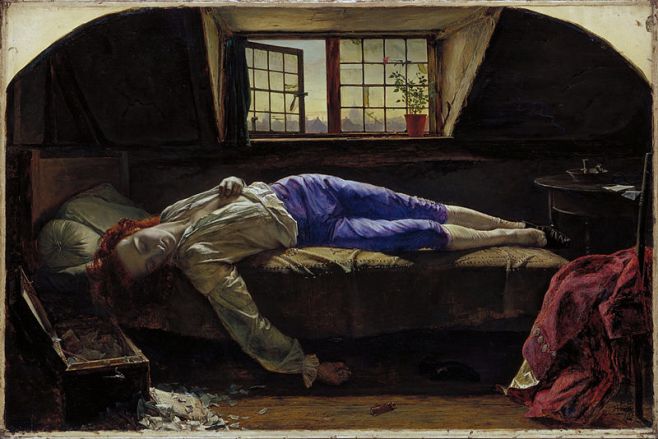

Chatterton (1856), by Henry Wallis. Tate. (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

Bill Gates, World Economic Forum 2007 (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Why? Matters to whom? Who gets to decide whose paintings are good enough for artists to “get rich” by, if not those who buy them? Whose ring are artists supposed to kiss – the leader of the Establishment, or the anti-Establishment? Is there some rule that artists have to prove themselves by suffering for some cause, starving in a garret, dying young, or perhaps killing themselves for being misunderstood, before they are promoted to Officially Important status?

Does it count that Tissot fought in the Franco-Prussian War? That he stayed in Paris during the Commune while his peers all fled and alone recorded mass executions by the French Government that no one wanted to know about at the time? That, after emigrating to London, he was no longer considered a real French artist, nor considered an English one, so his work must speak for itself? James Tissot became wealthy through his own independent nature, talent, and hard work; isn’t that something universally admired?

Enough people thought, and continue to think, well enough of Tissot’s work that they have paid enormous sums for it, and museum curators think highly enough of Tissot’s work that it hangs in major art museums around the world, from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Tate in London, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, to the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia. Why, then, is James Tissot even now such an object of scorn to certain people?

This New York Times reviewer in 1985 summed Tissot up as a “dexterous careerist” and “a minor master, in way above his head.” As a parting shot, he referred to Tissot’s mistress, the young divorcée Kathleen Newton, as a “concubine…lolling around like a beached porpoise,” modelling for “many a droopy painting.”

The Hammock (1879), by James Tissot. 50 in./127 cm. by 30 in./76.20 cm. Image courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot,” © 2012 by Lucy Paquette

The current EY Exhibition at Tate Britain, “The Impressionists in London: French Artists in Exile 1870-1904,” (through May 7, 2018) features a great deal of work by James Tissot, including some never before displayed in public, as well as a horrified letter he wrote to an English aristocrat describing executions he witnessed. While visitors are even now crowding around these items, many reviewers tore into Tissot in the days before the show opened.

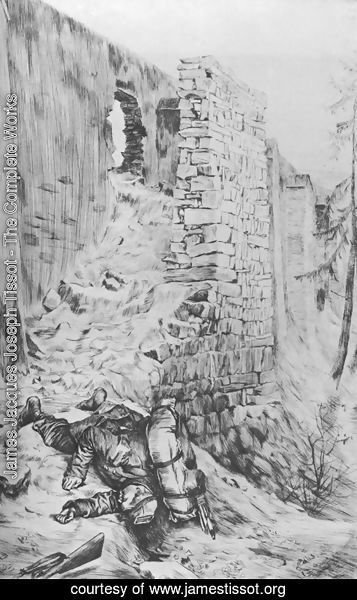

“How I despise the obsequies and sneers of James Tissot, his meringue frills and cupcake palette,” wrote the critic for London’s Evening Standard, who made no comment on Tissot’s elegant watercolor, The Wounded Soldier (c. 1870), or his May 29, 1871 watercolor of a dozen men being pushed off the ramparts outside Paris to their grisly deaths, a government massacre he witnessed.

Le premier homme tué que j’ai vu (Souvenir du siège de Paris) (The First Killed I Saw (Souvenir of the Siege of Paris)), by James Tissot. (Courtesy of http://www.jamestissot.org)

The Telegraph’s reviewer also ignored Tissot’s extraordinary war reportage, and let him have it: “Really, though, Tissot was a manicured and superficial fawner, with an excessive interest in flouncy, expensive women’s fashions. As an artist, he was always too eager to please.” He called Tissot’s work “irredeemably insincere” and “finicky,” filled with “meretricious flash and sparkle.”

The Financial Times’ art critic (the rare female) was sweet by comparison, merely lambasting Tissot’s “queasily compressed compositions” and “his easy facility and brittle surfaces.”

The Guardian’s critic termed Tissot a “bore” – “a famous one whose work is still familiar from greetings cards and paperback covers of classic novels.” He begrudgingly mentioned that Tissot, though an exile from French tumult, remained in London for a decade, “living in increasing affluence in St John’s Wood.” Tissot’s affluence seems to be the lightning rod for many, while this critic also trots out the charge of plagiarism made against Tissot by his frenemies, James McNeill Whistler and Edmond de Goncourt: “There’s a twist of Degas, a pinch from Manet, a whole subject from Whistler, all ironed flat by his noncommittal brushwork.” [See Was James Tissot a Plagiarist? and More “Plagiarists”: Tissot’s friends Manet, Degas, Whistler & Others.

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, also called Portrait of the Artist’s Mother (1871), by James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Portrait of Catrina Hooghsaet (1657), by Rembrandt van Rijn. Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd, Wales. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

To the left, Whistler with a soupçon of Rembrandt (right).]

The kiss of death from this Guardian critic? “He has more to offer the historian of costume than the historian of art.” But in 1869, the reviewer for L’Artiste praised this and more about Tissot’s work exhibited at the Paris Salon: “Our industrial and artistic creations can perish, our morals and our fashions can fall into obscurity, but a picture by M. Tissot will be enough for archaeologists of the future to reconstitute our epoch.”

The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth) c.1876, by James Tissot. Tate.

A week later, a different reviewer for The Guardian decried Tissot’s work for “how shallow and calculated some of his scenes are,” and was especially affronted that, “A woman accidentally displaying her bottom perfectly plays to Victorian sexual hypocrisy.” Clearly, the display of this bottom was not accidental.

But not all art critics despise Tissot and his work.

On the Thames (1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 74.8 by 110 cm. The Hepworth Wakefield. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot” by Lucy Paquette © 2012.

Time Out’s reviewer had just begun describing the Tate’s EY Exhibition for his readers, before his excitement brimmed over: “…then you get hit with a room full of James Tissot paintings, and that’s where it gets good. Tissot came to England to make a name for himself as a society painter, and boy did he ace it. His paintings of parties in mansions, picnics in the garden, trysts on the Thames are lush, cool, refined and debauched. His colours are deep and luxurious, his fabrics flowing and infinitely detailed. This is society painting at its finest: knowing, cynical and sexy. He’s an obscure and not particularly cool artist, but it’s such a treat to see so many of his works together.” (To hipsters and sophisticates, most people described as “knowing, cynical and sexy” would, indeed, be considered cool. Why not James Tissot?)

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), by James Tissot. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. (Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.)

I never have had to struggle through determined museum crowds to see a painting as I did at “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” at the Met in 2013. The dense, semi-circular crushes before Tissot’s The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children (1865), Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), and The Circle of the Rue Royale (1868) were astounding, and deserved. But a New York Times reviewer couldn’t resist disparaging the Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant as “zealously detailed,” when that’s why it’s so wonderful. People (including me) vied for a position close enough to examine its every exquisite detail, and the masterful brush curls of the gown’s ruffled edging.

Likewise at the Tate’s “Impressionists in London” recently, with waves of visitors flowing past, I had to anchor myself in front of Tissot’s The Wounded Soldier (1870) and his eyewitness account in watercolor, The Execution of Communards by French Government Forces at Fortifications in the Bois de Boulogne, 29 May 1871 (private collection), displayed in public for the first time.

Call James Tissot “devious,” “shifty,” “a manicured and superficial fawner,” whatever makes you feel superior to a man who’s been dead for 116 years but lives on in continued public popularity. It’s said, “The best revenge is living well,” and Tissot, with his champagne on ice for visitors at his large private villa in the leafy suburbs of London, his hot girlfriend, and his enormous self-generated income and therefore his independence, lived better than pretty much anyone. If you’ve got it, flaunt it.

“…there is something of the human soul in his work and that is why he is great, immense, infinite…”

Vincent van Gogh on James Tissot, in a letter to his brother, Theo, September 24, 1880

© 2018 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Thank you for celebrating my birthday with me, and please enjoy other posts on my blog as well as my book, The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot.

If you’d like to learn more about James Tissot and his work, see this show if you can, and let me know what you think:

“The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870 – 1904)”

November 2, 2017 – May 7, 2018

Tate Britain

Previous April Fool’s Day posts:

Was James Tissot a Plagiarist?

Tissot and his Friends Clown Around

Tissot’s Tiger Skin: A Prominent Prop

View my video, “The Strange Career of James Tissot” (Length: 2:33 minutes).

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

This is wondeful, Lucy

Best regards, Patricia http://www.patriciaoreilly.net

Thank you, Patricia!