To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “The James Tissot Tour of Victorian England.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2017/10/12/the-james-tissot-tour-of-victorian-england/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot fled the violence and chaos of the Paris Commune in June, 1871, after prospering under Napoléon III’s Second Empire and then fighting for his country in the Franco-Prussian War, to live and prosper in London during Queen Victoria’s reign until he returned to France in November, 1882.

A newspaper weather map from September 25, 2017 that I used to mark our progress.

I’ve just returned from my long-planned Victorian Tour of the U.K. with my husband and gained more understanding of the Victorian England that Tissot experienced. I studied Art History in London for a year when I was in my twenties, and since I married, my husband and I have traveled in the U.K. together three times, exploring London, Bath, Cambridge, Ely, Bury St. Edmunds, and Laycock. On this trip, we were focusing on the Victorian experience, but without doubt, we missed a great deal in two weeks, and I’d like to hear from those of you familiar with other not-to-be-missed Victorian sights. Relying on trains, we traveled from Manchester to Liverpool, York, Nottingham, Birmingham, and London, for the most part staying in Victorian-era hotels, dining in Victorian pubs, and visiting Victorian art collections and points of architectural interest. These are some of my photos – and some by my husband, who really is the best traveling companion I could ever wish for.

Manchester Town Hall, with the Albert Memorial in the left foreground.

We started in Manchester, a handsome, exciting city combining the grandeur of its Victorian architecture with the sophistication of its modern energy.

Manchester, or “Cottonopolis,” was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, and it became a city in 1853. We saw a demonstration of original 19th century textile mill machinery spinning cotton yarn into cloth at The Museum of Science and Industry, and we learned a bit about the working conditions at the mills. Manchester – dirty, noisy and overcrowded – was the model for Milton in British novelist Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South, published in 1855, which centers on the romance between the idealistic Margaret Hale and cotton-mill owner John Thornton.

A nook in the Sculpture Hall Café in the Town Hall.

The cotton industry made Manchester the wealthiest city in the British Empire during that time, and its architecture reflected that proud status. The magnificent Gothic Revival Town Hall (1868 – 1877) designed by Alfred Waterhouse (1830 – 1905) dominates the city center, and its Sculpture Hall Café offers a secluded, rather posh environment for brunch or afternoon tea amid marble busts of former town alderman and other local dignitaries of the era.

In front of the Town Hall, in Albert Square, Manchester’s Albert Memorial was completed in 1865 as the first of several memorials to Prince Albert (1819 – 1861) including the one designed by Sir Gilbert Scott (1811 – 1878) in Kensington Gardens, London, unveiled by Queen Victoria in 1872.

It was easy to find Tissot’s “Hush (The Concert, 1875)” at the Manchester Art Gallery.

In 1876, James Tissot began exhibiting his work outside London, marketing it to the newly-rich men of the Industrial north. Today, six of his finest works can be found in museums there. The Manchester Art Gallery’s collection includes Hush! (The Concert), painted in 1875 and displayed at the Royal Academy exhibition at the height of Tissot’s success in London. The collection also includes The Warrior’s Daughter (A Convalescent, c. 1878), which was not on display when we visited.

A Visit to the Yacht (c. 1873), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

British painter George Adolphus Storey (1834 – 1919), in his 1899 memoirs, described a high-spirited “railway picnic party” in 1873 with a large group of men returning from a lavish house party in Manchester hosted by art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910): Tissot, painters Ferdinand Heilbuth (1826 – 1889), Philip Hermogenes Calderon, R.A. (1833 – 1898), George Dunlop Leslie, A.R.A. (1835 – 1921), David Wilkie Wynfield (1837–1887), William Yeames, A.R.A. (1835 – 1918), and Frederick Walker (1840 – 1875), editor Shirley Brooks (1816 – 1874) and “the Punch men,” pianist, conductor and composer Frederic Hymen Cowen (1852 – 1935), and a host of others including opera star Charles Santley (1834 – 1922), who “sang us many of his delightful songs.”

Tissot’s work was being purchased by the newly-rich in Northern England as early as 1873, when he painted A Visit to the Yacht, which he sold directly to Agnew’s, London for £650, as La Visite au Navire. Shortly after, Agnew’s, Liverpool sold the picture to David Jardine (1827 – 1911), a Liverpool timber broker, ship owner and art collector who eventually became Chairman of the Cunard Steamship Company.

With Tissot’s Portrait of Mrs Catherine Smith Gill and Two of her Children (1877) at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

We took a day trip to the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool to see Tissot’s Portrait of Mrs Catherine Smith Gill and Two of her Children (1877), one of the largest works he ever had produced.

Mrs. Gill’s husband, Mr. Chapple Gill (c.1833 – 1901/2), was the son of Robert Gill, a Liverpool cotton broker of Knotty Cross and R. & C. Gill; the son joined the business in 1857 and had risen to senior partner [by 1880, he became head of the firm]. He commissioned French painter Tissot, then living in London, to paint a portrait of his wife, Catherine Smith Carey (1847-1916), whom he had married on June 10, 1868 at Childwall. She was the only child of Thomas Carey (1809 – c. 1875), a wealthy, retired estate agent. Tissot’s portrait of Catherine Smith Gill shows her – heiress at age 30 – sitting in the drawing-room window of her mother’s home at Lower Lee, at Woolton near Liverpool, which was built by Catherine’s father. Tissot lived at the red sandstone mansion for eight weeks while painting the portrait, in which he depicts Catherine with her two-year-old son Robert Carey and six-year-old daughter Helen; she was to have another boy and two more girls.

Outside Liverpool, we visited Sudley House, the former home of George Holt (1825 – 1896), a self-made Victorian shipping-line owner and merchant who built an impressive art collection that includes work by Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds, Edwin Landseer, J.E. Millais, and J.M.W. Turner. Since British aristocrats did not patronize contemporary French painters, George Holt was just the type of client that Tissot catered to in England: newly-wealthy men who would invest in art purchased from dealers and at exhibitions rather than from commissions. Since there is no home of a contemporary client of Tissot’s to tour (e.g. Mr. Chapple Gill), it was quite insightful to see George Holt’s home and collection, now managed by National Museums Liverpool.

Kirkgate at the York Castle Museum.

My indefatigable husband and travel partner.

We continued our Victorian Tour in York, at the York Castle Museum’s Kirkgate, a recreated Victorian street where we were immersed in the experience of strolling over the cobblestones past the goods on display for the rich and the backstreets of the poor. Kirkgate has everything from a hansom cab like the one Tissot depicted in Going to Business (Going to the City, c. 1879), to a confectioner’s, schoolroom, police cell, millinery shop, watch shop, a gentleman’s clothier, stables, privy, and alleys, one of which smelled strongly of horse manure in a distinctly authentic sensory detail. The shops are based on real York businesses that operated between 1870 and 1901. Afterwards, I tried on a bustle gown and smart little chapeau. While the gown was just a costume, without a corset or foundation garments, I was surprised how very hot, heavy, and constricting it felt.

At the York Castle Museum, in front of the Victorian parlor.

During our visit to the National Railway Museum in York, we were able to look in the windows of Queen Victoria’s palatial train carriages, upholstered in yards of bright blue silk, as well as a train outfitted by King Edward VII in 1902 for his own use, complete with a smoking saloon and full bathroom. It was Queen Victoria’s delight in train travel than soothed the qualms of the general public, frightened that the wind generated by the speed of this new mode of transportation would blow their heads off.

One of Queen Victoria’s royal train carriages.

Gentleman in a Railway Carriage (1872), by James Tissot. Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (Photo: Wikiart)

Lucy in a railway carriage.

We continued on to Nottingham, a bustling city boasting glorious Victorian buildings by architects including Watson Fothergill (1841 – 1928), who designed over a hundred houses, banks, churches, shops and warehouses in the Nottingham area from about 1864 to 1912.

A Fothergill design.

Nottingham.

Though Fothergill’s Gothic Revival and Old English vernacular style buildings now are interspersed with modern architecture, we felt surrounded by the Victorian experience.

Nottingham Station, first built by the Midland Railway in 1848, designed by architect J.E. Hall of Nottingham.

Tissot’s Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern (1874) was exhibited at Nottingham Castle, still an art gallery today, and at Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1887.

Waiting for the Ferry at the Falcon Tavern (1874), by James Tissot. Speed Museum, Louisville, Kentucky, U.S.A.

In Birmingham, where the industrial steam engine was invented and which became a manufacturing powerhouse, the architecture was grander than in Nottingham. Queen Victoria granted Birmingham city status in 1889, and the vibrant center of the second most populous city in Britain is now under the gaze of the bronze monument to her in Victoria Square.

In Birmingham, where the industrial steam engine was invented and which became a manufacturing powerhouse, the architecture was grander than in Nottingham. Queen Victoria granted Birmingham city status in 1889, and the vibrant center of the second most populous city in Britain is now under the gaze of the bronze monument to her in Victoria Square.

We received a lovely private tour of Birmingham’s Anglican Cathedral from a kind and knowledgeable volunteer on duty. Designed in the Baroque style in 1715, it features soaring Pre-Raphaelite stained glass windows designed and manufactured by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris in 1880. The Cathedral was bombed during World War II – just after the priceless stained glass windows had been removed and hidden in a slate mine in Wales.

Walking along a Victorian-era street in Birmingham.

We viewed the Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces at the imposing Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, opened by the Prince of Wales in 1885, during a leisurely afternoon before relaxing over tea in the Edwardian Tea Rooms.

Resting at the Edwardian Tea Rooms.

The common yard of the Birmingham Back to Backs.

Outside the common laundry room.

Dashing to the other side of town, we missed the last house tour of the day at the Birmingham Back to Backs, operated as a museum by the National Trust, but the staff kindly allowed us to look at the exhibit above the gift shop and also to walk around the common yard that was shared by several families who lived in these inner-city homes that were three storeys high and one room deep. Restored by the Birmingham Conservation Trust in collaboration with architects S. T. Walker & Duckham, the Back to Backs were opened to the public in 2004 as the city’s last surviving example of such houses. After the Public Health Act of 1875, no more back to backs were built, but people continued to live in the crowded existing housing units until the 1950s. Thousands of similar houses were built throughout the 19th century, for the rapidly increasing population of Britain’s expanding industrial towns, including the families of workers in button making, glass work, woodwork, leather work, locksmithing, tailoring, and jewelry trades. The common yard was quite small for exercise of those many family members, with a shared laundry room and privies.

While James Tissot was wealthy and would have had little contact with this aspect of Victorian life, it nevertheless was the social reality of his time and the underpinning of many luxury goods and services he would have purchased.

St. Pancras International

In London, we stayed near St. Pancras rail station, the most splendid Victorian edifice of all. Designed by Sir Gilbert Scott (1811 – 1878) and opened in 1868, it was a marvel of Victorian engineering and a masterpiece of Victorian Gothic architecture.

A staircase in the St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel.

St. Pancras Station was built by the Midland Railway Company to connect London with some of England’s major cities: Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Bradford. By 1876, the station offered services to Edinburgh. In June, 1874, the first Pullman service in the U.K. was available, with a restaurant car and sleeping accommodations, and by 1878 this service extended to the northern tip of Scotland.

So when James Tissot participated in that “railway picnic party” in 1873, returning from art dealer William Agnew’s lavish house party in Manchester, he would have traveled to and from the sumptuous new St. Pancras Station, convenient to his villa in St. John’s Wood.

Another view of the staircase.

St. Pancras declined over time and finally was restored from 2004 – 2007, officially re-opening as St. Pancras International in 2007 in an elaborate opening ceremony attended by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, with a concert performed by the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra. Passengers now can travel to Paris and Brussels, among other destinations.

Inside and out, St. Pancras International and the luxury five-star St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel, which was the talk of London when it opened in 1876, are simply jaw-dropping. My husband and I had cocktails at The Gilbert Scott bar, where I couldn’t take my eyes off the shimmering painted ceiling.

The ceiling in The Gilbert Scott at the St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel.

The Regent’s Park.

The Regent’s Park.

Another incredible place that James Tissot lived near and would have enjoyed is The Regent’s Park, developed by architect John Nash (1752 – 1835), a friend of the Prince Regent (later King George IV). A vast, rounded green area north of London, The Regent’s Park features a large lake, landscaped gardens, an open-air theater, the London Zoo, and much more.

Tissot’s friend since 1859, the Dutch-born painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836 –1912), lived in Townshend House on the north side of the park near the Regent’s Canal, which we cruised along in a canal boat.

A waterbus on the Regent’s Canal.

Later, we visited the exotically-decorated Leighton House Museum, the former home of the distinguished Victorian artist Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830 – 1896), in Holland Park. There we viewed the extensive Alma-Tadema exhibition, “Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity,” (July 7 – October 29, 2017), the largest exhibition devoted to the extraordinarily successful Victorian painter held in London since 1913. The exhibition includes a few contemporary photos of the house at 17 (now 44) Grove End Road in St. John’s Wood that Alma-Tadema purchased from James Tissot in 1883 and lived in from 1885 until his death in 1912. In 2014, my husband and I toured this large home, now a private residence.

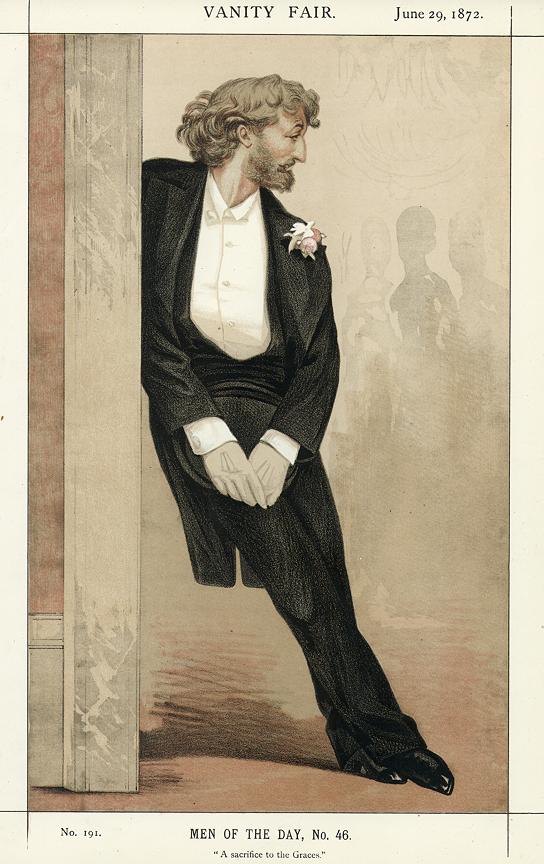

Caricature of Frederic Leighton, by James Tissot. Published in Vanity Fair on June 29, 1872, the caption reads “A sacrifice to the Graces.” (Photo: Wikimedia.)

Queen Victoria’s Coronation gown and golden robe.

At Kensington Palace, we took in the “Victoria Revealed” exhibit (through November 12, 2017), walking through the rooms in which the young princess resided. I saw the staircase below the room she was in when she learned that her uncle had died and, at age 18, she had become Queen. Here in the Red Saloon, she held her first Privy Council meeting.

Several of Victoria’s gowns were on display, including her delicate gold coronation robe replicated for the current television drama “Victoria,” starring Jenna Coleman, as well as a smart military-style riding jacket with a waist so small it is hard to believe anyone could ever wear it.

A resplendent staircase at Kensington Palace.

The staircase to the room that Victoria was in when she learned that she was Queen, with a quote from her diary.

Foreign Visitors (1874), by James Tissot.

My husband and I spent a lot of time at Trafalgar Square, where the portico of the National Gallery of Art and the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields provided the backdrop (though slightly altered, which did not endear him to the British art critics) for Tissot’s two versions of Foreign Visitors (1874). Tissot exhibited the larger version at the Royal Academy in 1874.

On the last day of our Victorian Tour, where else could we have afternoon tea but in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s luxurious Gamble, Poynter, and Morris Rooms, beckoning with multi-colored ceramic, stained glass and enamel, opened in 1868 as the first-ever museum restaurant?

The scones, as big as our faces, were a fitting finale to our Victorian tour – along with one last trip from the awe-inspiring St. Pancras station.

Ceramic-lined staircase at the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Gamble Room at the V&A (with updated lighting fixtures).

The Poynter Room at the V&A.

One last chance for afternoon tea – until next time!

© 2017 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related Posts:

A visit to James Tissot’s house & Kathleen Newton’s grave

The James Tissot Tour of Paris

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.