To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “French Painter James Tissot’s British Clients: Rising Industrialists, by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2018/04/15/french-painter-james-tissots-british-clients-rising-industrialists-by-lucy-paquette-for-the-victorian-web/. <Date viewed.>

The Victorian Web, a vast resource on literature, history and culture in the age of Victoria, published this article in March, 2018:

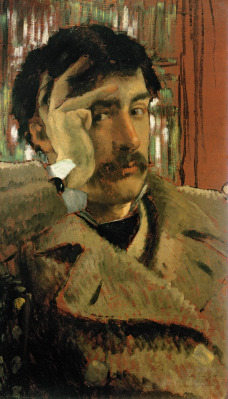

By 1865, French painter James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836 – 1902) was earning 70,000 francs a year, and had found his entrée to aristocratic patronage with The Marquis and the Marchioness of Miramon and their children (1865, Musée d’Orsay) on the terrace of the Château de Paulhac in Auvergne. The next year, the marquis commissioned Tissot to paint Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née Thérèse Feuillant (1866, Getty Museum, Los Angeles) in her sitting room at the château.

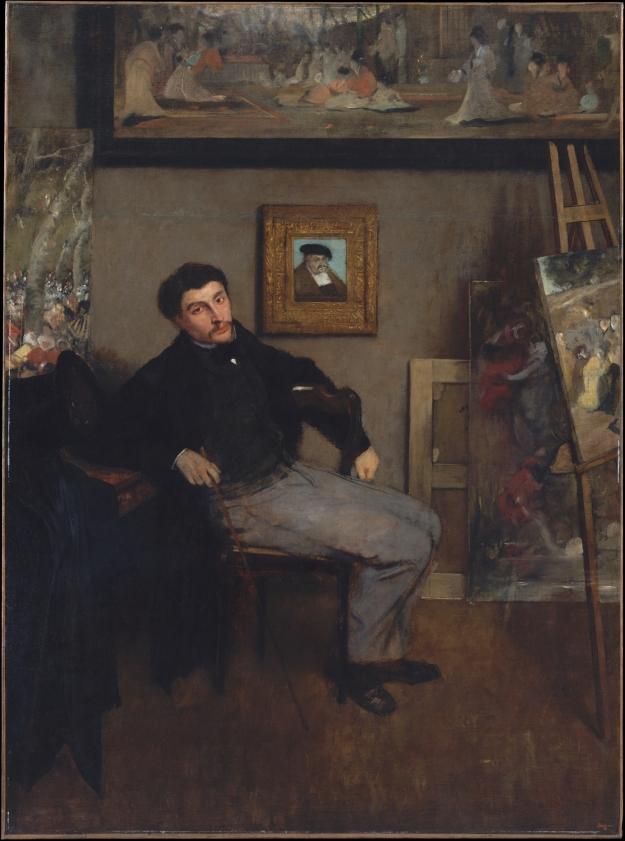

In 1867, while Tissot’s opulent new villa on the most fashionable of Baron Haussmann’s boulevards was under construction, he painted the president of Paris’ exclusive Jockey Club, Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1824 –1896), now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He moved into his elegant house by 1868, the year he painted a hearty slice of the French aristocracy in a group portrait of an exclusive club, founded in 1852, The Circle of the Rue Royale (1868, Musée d’Orsay). At the Salon in 1868, Tissot exhibited two oil paintings, one of which, Beating the Retreat in the Tuileries Gardens (private collection), was purchased by Napoleon III’s influential cousin, Princess Mathilde.

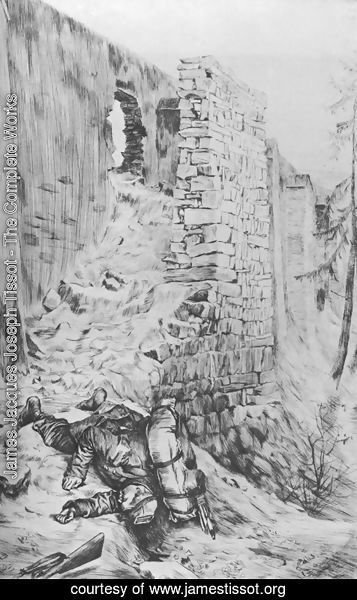

But after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71, and its bloody aftermath, the Paris Commune uprising in the spring of 1871, Tissot moved to London. Within two years, he established himself in a large house in the London suburb of St. John’s Wood with a studio, a conservatory and a luxurious garden. While British aristocrats did not purchase the French artist’s paintings, plenty of newly-wealthy industrialists sought his work as they enhanced their social status by building art collections. Because provenance (the history of ownership) of Old Masters paintings was not always meticulously documented at this time, many new collectors – wary of fakes – concentrated on contemporary artists so they would know exactly what they were getting for their money.

William Agnew (1825 – 1910), the most influential art dealer in London, specialized in “high-class modern paintings” and represented Tissot for a time during the 1870s. Tissot’s The Last Evening was purchased from Agnew’s by Charles Gassiot (1826 – 1902), a London wine merchant and art patron who lived in a mansion in Upper Tooting, Surrey. Gassiot bought The Last Evening in February, 1873, before it was exhibited at the Royal Academy, for £1,000. Gassiot also purchased Tissot’s Too Early, from Agnew’s in March, 1873 (before its exhibition at the Royal Academy that year), for £1,155. Gassiot and his wife Georgiana, a childless couple, donated a number of his paintings, including The Last Evening and Too Early, to the Guildhall Art Gallery from 1895 to 1902.

A Visit to the Yacht (c. 1873), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Tissot sold La Visite au Navire (A Visit to the Yacht, private collection) to Agnew’s, London, in mid-June 1873. Less than five months later, at the beginning of November, Agnew’s, Liverpool sold the painting to art collector David Jardine (c. 1826 – 1911) of Highlea, Beaconsfield Road, Woolton. Jardine, a timber broker and ship owner, was the head of Farnworth & Jardine, world famous for their mahogany auctions; a man of considerable ability and courtesy, he was well liked for his “courtly bearing.”

Les Adieux (Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, U.K.) was reproduced as a steel engraving by John Ballin and published by Pilgeram and Lefèvre in 1873 – an indication of its popularity. The picture was owned by wealthy international railway contractor Charles Waring (c. 1827 – 1887).

The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874, Tate) was purchased from Tissot by William Agnew the year it was completed and sold to Hilton Philipson (1834 – 1904), a solicitor and colliery owner living at Tynemouth. (Philipson also spent 620 guineas at Agnew’s for John Everett Millais’ 1874 painting, The Picture of Health, a portrait of Millais’ daughter, Alice (later Mrs. Charles Stuart Wortley).

The Empress Eugénie and the Prince Impérial in the Grounds at Camden Place, Chislehurst (c. 1874), by James Tissot

In 1874, two of James Tissot’s paintings were purchased by aristocrats, one Irish and the other French. Mervyn Wingfield, 7th Viscount Powerscourt (1836 – 1904), whose forebears had lived since 1300 on a magnificent estate outside Enniskerry, County Wicklow, Ireland, paid £1,000 for Avant le Départ (private collection). By autumn, Tissot was commissioned to paint a double portrait of the exiled Empress of France, widow of Napoléon III, Eugénie de Montijo (1826 –1920), and their son, The Empress Eugénie and the Prince Impérial in the Grounds at Camden Place, Chislehurst (c. 1874, Musée Nationale du Château de Compiègne, France). However, these sales were anomalies, and his clients continued to be industrialists.

The Convalescent (1875/1876), by James Tissot. Museums Sheffield, U.K.

Kaye Knowles, Esq. (1835-1886), was a London banker whose vast wealth came from shares in his family’s Lancashire coal mining business, Andrew Knowles and Sons. Knowles, a client of London art dealer Algernon Moses Marsden [1848-1920, see Who was Algernon Moses Marsden?], owned a large art collection, including works by Sir Edwin Landseer, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Rosa Bonheur, Giuseppe De Nittis, Atkinson Grimshaw and Édouard Detaille. He eventually owned four oil paintings by James Tissot, including The Empress Eugénie and the Prince Impérial in the Grounds at Camden Place, Chislehurst; On the Thames (1876, The Hepworth Wakefield, U.K.); and In the Conservatory (also known as Rivals, c. 1875-1876, Private Collection). Incidentally, after Knowles’ sudden death, In the Conservatory (Rivals) was sold with his estate as Afternoon Tea by Christie’s, London, on May 14, 1887. William Agnew bought the painting at this sale for 50 guineas and passed it to one of Kaye’s executors, his brother, Andrew Knowles, on May 16, 1887. Andrew Knowles also owned The Convalescent (1875/1876, Museums Sheffield, U.K.), which was exhibited at the 1876 Royal Academy exhibition.

Chrysanthemums (c. 1874-76), by James Tissot. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute at Williamstown, Massachusetts

Chrysanthemums (c. 1874-76, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute at Williamstown, Massachusetts) was purchased by British cotton magnate, MP and contemporary art collector Edward Hermon (1822 – 1881) by 1877. Hermon eventually owned over 70 paintings, including works by J.M.W. Turner, Sir Edwin Landseer, and John Everett Millais, which he displayed in the picture gallery of his magnificent French Gothic estate, Wyfold Court, built at Rotherfield Peppard, Oxfordshire between 1872 and 1878.

Portsmouth Dockyard (c. 1877, Tate) originally was owned by Henry Jump (1820 – 1893), a wealthy Justice of the Peace and corn merchant living at Gateacre, Lancashire.

Portrait of Mrs Catherine Smith Gill and Two of her Children (1877), by James Tissot. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, U.K.

Mr. Chapple Gill (c.1833 – 1901/2), was the son of Robert Gill, a Liverpool cotton broker of Knotty Cross and R. & C. Gill; the son joined the business in 1857 and had risen to senior partner [by 1880, he became head of the firm]. In 1877, he commissioned French painter Tissot, then living in London, to paint a portrait of his wife, Catherine Smith Carey (1847-1916), whom he had married on June 10, 1868 at Childwall. She was the only child of Thomas Carey (1809 – c. 1875), a wealthy, retired estate agent. Tissot’s portrait of Catherine Smith Gill (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) shows her – heiress at age 30 – sitting with her two children in the drawing-room window of her mother’s home at Lower Lee, at Woolton near Liverpool, which was built by Catherine’s father.

William Menelaus (1818 – 1882) was a Scottish-born engineer, iron and steel manufacturer, and inventor. Widowed after only ten weeks of marriage, he never remarried but raised two nephews (William Darling, who became a law lord, and Charles Darling, who became an MP and later a baron). Menelaus earned a fortune at the Dowlais Ironworks in South Wales, and his only extravagance was his art collection, which was said to fill his home in Merthyr. He donated pieces to the Cardiff Free Library, then upon his death, bequeathed to it the remaining thirty-six paintings, valued at £10,000. His bequest included James Tissot’s Bad News (The Parting), 1872, now at the National Museum Cardiff.

Quiet (c. 1881), by James Tissot. Private Collection.

Quiet (c. 1881) was purchased by Richard Donkin, M.P. (1836 – 1919), an English shipowner who was elected Member of Parliament for the newly created constituency of Tynemouth in the 1885 general election. The small painting remained in the family and was a major discovery of a Tissot work when it appeared on the market in 1993, selling for $ 416,220/£ 280,000. In perfect condition, it shows Tissot’s mistress and muse, Kathleen Newton (1854 – 1882), and her niece, Lilian Hervey in the garden of Tissot’s house at 17 Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, in north London. It was Lilian Hervey who, in 1946, publicly identified the model long known only as “La Mystérieuse” – the Mystery Woman – as her aunt, Kathleen Newton.

The story of James Tissot’s Victorian patrons is the story of social transition: in the late nineteenth century, art collecting ceased to be the prerogative of the aristocracy and became a status symbol for the rising industrial class. The wealth of contemporary collectors of Tissot’s oil paintings gives an idea of the monetary value of his canvases as well as their perceived value as status symbols.

On the Thames, A Heron (c. 1871-1872), by James Tissot. Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

An interesting side note is that, for one prominent financial dynasty, the value of Tissot’s paintings as investments did not hold. On the Thames, A Heron (c. 1871-1872, Minneapolis Institute of Arts) was one of Tissot’s first paintings after his arrival in London – and it was the first on record to be sold at auction in England. Calculated to appeal to Victorian tastes, this Japanese-influenced scene initially was owned by London banker José de Murrieta (c. 1834 – 1901), a member of a Spanish family who had made their fortune within two generations by trading, especially with Argentina. Murrieta tried to sell the painting in May, 1873 as On the Thames: the frightened heron for 570 guineas, but it did not find a buyer. José, who was married, lived at Wadhurst Park in East Sussex, designed by E.J. Tarver in 1872-75. It was purchased by his bachelor brothers Cristobal (1839 – 1891) and Adriano (1843 – 1891); they resided in the mansion they built about 1854 at 11, Kensington Palace Gardens (which was decorated by Alfred Stevens, with Walter Crane painting a frieze in the ballroom they added in 1873). José and his intelligent and witty wife, Jesusa (c.1834 – 1898), were members of the Prince of Wales’ set and entertained lavishly at the houses in London and Sussex, both showcases for the vast collection of modern British and Continental painting they had amassed. The Prince scandalized the Foreign Office before and after his trip to India by traveling to Menton on the Mediterranean for Easter with Mrs. Murrieta in March 1875, and spending three days sightseeing with her in April, 1876, while he stayed at lodgings taken for him under an assumed name. José soon received royal favor himself, being created the first Marques de Santurce in October 1877 by 20-year-old King Alfonso XII of Spain. Meanwhile, Lillie Langtry, a young married beauty from Jersey, consumed the Prince’s interest from mid-1877, and it was rumored that the Murrietas created a love nest for the Prince and her at Wadhurst. The Prince’s attentions wandered by mid-1880, but by 1881, another wing had been added to Wadhurst to entertain him. Within two years, the art collection was expendable. In April 1883, among other paintings including a Turner and several Alma-Tademas, José offered At the Rifle Range (1869, Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire) for sale at Christie’s, London as The Crack Shot; at £220.10s, it failed to find a buyer. In June 1883, José attempted and failed to sell On the Thames for 273 guineas. The Murrietas, who invested heavily in Argentinian railways, were bankrupted in 1890, when Argentina defaulted on bond payments.

Afternoon Tea, by James Tissot. Private Collection.

Had José de Murrieta known that London wine merchant Charles Gassiot purchased The Last Evening in February, 1873 for £1,000 and Too Early in March, 1873 for £1,155, perhaps he might have been able to sell him On the Thames: the frightened heron for 570 guineas in May, 1873. The Spanish banker might have been prudent to have tried slipping his “high-class modern paintings” past William Agnew’s discerning taste; then again, Agnew snapped up Afternoon Tea at Christie’s in 1887 for a mere 50 guineas. In 2013, this picture was deaccessioned [regrettably] by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York – selling at Christie’s, New York to a private collector for $1,700,000 (Hammer price).]

© 2018 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

My thanks to The Victorian Web‘s Editor-in-Chief and Webmaster, George Landow, and to Associate Editor Jackie Banerjee.

Selected Bibliography

Brooke, David S. “James Tissot and the ‘Ravissante Irlandaise.'” Connoisseur. May 1968.

Graves, Algernon, F.S.A. Art Sales from Early in the Eighteenth Century to Early in the Twentieth Century. London: Algernon Graves, 1918.

Misfeldt, Willard E. James Jacques Joseph Tissot: A Bio-Critical Study. Ph.D. diss. Ann Arbor: Washington University, 1971.

Paquette, Lucy. “Who was Algernon Moses Marsden?” The Hammock. Web. 26 March 2018.

Ridley, Jane. The Heir Apparent: A Life of Edward VII, The Playboy Prince. New York: Random House, 2013.

Wadhurst History Society Newsletter. Web. 26 March 2018.

See my other articles on The Victorian Web:

A James Tissot Chronology, by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web

James Tissot (1836-1902): a brief biography by Lucy Paquette for The Victorian Web

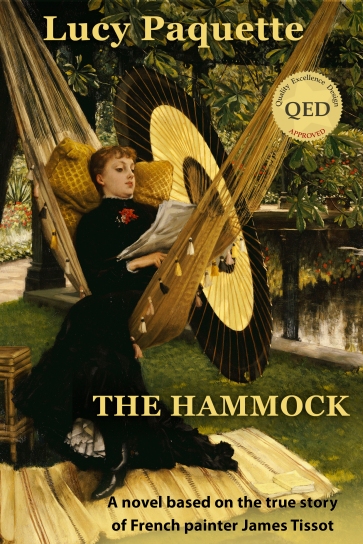

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

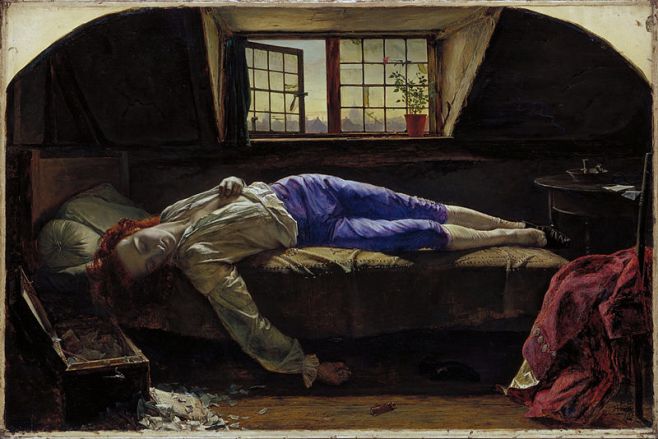

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download