To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. Of Snobbery, Death & Parlormaids: Millais, Alma-Tadema & Whistler, 1869. The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/01/25/of-snobbery-death-parlormaids-millais-alma-tadema-whistler-1869/. <Date viewed.>

In March 1869, Millais, now 40, was in Hastings, recuperating from typhoid. Several weeks later, at the Royal Academy, he exhibited a portrait of his deer-stalking friend, the millionaire London Underground engineer John Fowler, as well as Vanessa, both painted the previous year. But he was prolific, and he also exhibited The Gambler’s Wife, A Dream of Dawn, The End of the Chapter and Miss Nina Lehmann, daughter of F. Lehmann, Esq.

Vanessa (1868), by John Everett Millais (Photo: Wikipedia)

In these years, while living at 7 Cromwell Place near the South Kensington Museum, John and Effie Millais socialized at grand balls and state receptions with the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland, Cyril Flower (later Lord Battersea), and foreign dignitaries including Italy’s General Garibaldi, Prince Alexander of Bulgaria and the Shah of Persia. Millais’ personal friends included notable literary, music, theatrical, scientific and political, diplomatic, and military figures.

Even so, while stag hunting in Scotland this year, Millais was frustrated to find the beats designated according to social rank, so that the lords and baronets were given the best shooting opportunities and Millais was relegated to stalking ground where there were no deer. Still, he characteristically referred to these men as “capital” chaps and only regretted that the snobbery was rather unsportsmanlike.

Whistler, living in London and still discouraged, had nothing to show for his artistic experimentation. For all his earnest attempts, he did not complete any new work in 1869. He had not exhibited his work since the Paris World Exposition in 1867. He feared being rejected by the Salon and Royal Academy, and if his work was accepted, he feared the humiliation that it would be badly hung.

Whistler lived in some elegance at 2 Lindsay Row (now 96 Cheyne Walk), near Battersea Bridge, where he had moved upon his return from Valparaiso at the end of 1866. He had broken off with Joanna Heffernan, though they saw each other occasionally. Jo had been virtually his wife from 1861, modeling for him, managing his household and helping him sell his work. But by 1869, at 35, Whistler had eyes for at least one other woman: Louisa Fanny Hanson, age 20. She is believed to have been a parlormaid from Clapham; she was the daughter of Frances Hanson, née Raymond, and Henry Hanson, a groom.

At this time, Tissot’s Dutch friend, Lourens Tadema (later Lawrence Alma-Tadema) was much decorated. Living in Brussels, he had earned a gold medal at Paris in 1864 and a second-class medal at the International Exhibition at Paris in 1867; he was made a member of the Academy of Fine Arts at Amsterdam in 1862, a Knight of the Order of Leopold (Belgium) in 1866, a Knight of the Dutch Lion in 1868, and he was made a Knight First Class of the Order of St. Michael of Bavaria in 1869.

His art dealer, the influential Ernest Gambart who maintained his Continental office in Brussels, kept him close. In 1869, Gambart decided to enter two of Tadema’s best paintings – A Roman art lover: (Silver statue) (No 108, 1868) and The pyrrhic dance (No 111, 1869) – into the exhibition of the Royal Academy, now relocated from the National Gallery to Burlington House in Piccadilly. They were entered under the category of foreign works, and they immediately drew the ire of prominent art critic John Ruskin (whose marriage to Effie Millais was annulled in 1854). Ruskin, now 50, described The pyrrhic dance as:

“the most dastardly of all these representations of classic life, was the little picture called the Pyrrhic Dance, of which the general effect was exactly like a microscopic view of a small detachment of black-beetles in search of a dead rat.”

The pyrrhic dance (No 111, 1869), by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Photo: Wiki)

On May 28, 1869, Tadema’s wife of six years died of smallpox at the age of 32. Marie-Pauline Gressin Dumoulin was the daughter of a French journalist, and it was on their honeymoon in Italy in 1863 – his first visit there – that he had been inspired to paint the life of ancient Rome. He had painted her only a few times, as in My Studio (1867), and after her death, he never spoke of her again. She left him with two young children – daughters, Anna (age two) and Laurense (age five). His son had died of smallpox just four years earlier, in 1865. Grief-stricken, Tadema’s health began to suffer, and he did not paint again until that autumn. Tadema’s unmarried sister, Artje, had lived with him and Pauline; now she helped with the children and kept house for her brother at 29 Rue de la Limite.

My Studio (1867) by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Photo: Wikiart)

When Tadema’s doctors were unable to diagnose his medical problems, Gambart advised him to consult with English physician Sir Henry Thompson (1820 – 1904). Thompson,* who had been knighted two years ago, was a surgeon and professor at University College Hospital. Six years earlier, he had performed a successful operation on the King of Belgium, who suffered from kidney stones. In London, on December 26, Tadema attended a dance at the home of painter Ford Madox Brown (1821 – 1893) – and met Laura Theresa Epps (1852 – 1909). The daughter of a doctor, Laura was a seventeen-year-old redhead – tall, slim, elegant, educated, musical, and interested in art – and the 33-year old Lourens Tadema fell in love with her.

Portrait of Miss Laura Theresa Epps (Lady Alma-Tadema), by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Photo: Wiki)

Tadema did complete a number of paintings in 1869, including The convalescent (No 113, 1869), the first he completed after his wife’s death. Others included A Wine Shop, Confidences, A Greek Woman, The Crossing of the River Berizina, and An Exedra.

Meanwhile, James Tissot had been enjoying his enormous success in Paris for only about five years, and his villa only since early 1868. He was 33, and 1869 would be his final full year to enjoy the elegant, carefree life he had made for himself in the French capital. His lucrative new sideline – contributing full-color political cartoons to London’s ground-breaking Society magazine, Vanity Fair – would open a new market for his work and would be, perhaps, the best bit of luck ever to happen to James Tissot.

Sir Henry Thompson * also was an artist who exhibited his paintings at the Royal Academy and the Salon in Paris.

© 2013 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Watch my new video, “The Strange Career of James Tissot” (Length: 2:33 minutes)

Exhibition note:

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900

February 17–May 19, 2013 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The first major survey of the art of the Pre-Raphaelites to be shown in the United States features some 130 paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and decorative art objects.

For more information, visit http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/preraphaelites.shtm

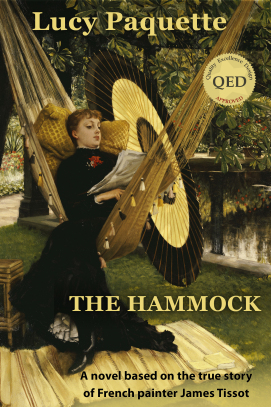

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.