To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. ““Napoleon is an idiot”: Courbet & the Fall of the Second Empire, 1870.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/02/28/napoleon-is-an-idiot-courbet-the-fall-of-the-second-empire-1870/. <Date viewed.>

Napoléon III (Wikimedia.org)

On July 15, 1870, Napoléon III, Emperor of the French, heeding his advisors in a diplomatic quarrel regarding the succession to the Spanish throne, declared war on Prussia – and its well-equipped and impeccably-trained army of more than 500,000 men with 160,000 reserves. France’s troops, disorganized and short of everything from maps to ammunition, numbered less than 300,000. “We do not have sufficient troops. I regard us already as lost,” the Emperor wrote to the Empress Eugénie, who was Regent in his absence. Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, unlike the Empress Eugénie, did not want France to go to war, and she had told Napoléon III – her cousin – that he was unfit to take personal command of the French army.

Gustave Courbet, at 51 was fresh from the glory of having refused the Legion of Honor, the highest decoration in France, from the minister of Beaux-Arts in the cabinet of Napoléon III’s reform-minded premier, Émile Ollivier, in late June. On July 15, 1870, Courbet wrote his loving and loyal mother, father and sisters in Flagey, a village in eastern France: “War is declared. Everybody is leaving Paris.” By the end of his letter, he added, “In everyone’s opinion I am the greatest man in France. My sensation lasted three weeks in Paris, in the provinces, and abroad. Now it is over. The war has taken my place.” On August 9, he wrote them, “We are passing through an indescribable crisis. I do not know how we shall come out of it. Monsieur Napoléon has declared a dynastic war for his own benefit and has made himself generalissimo of the armies, and he is an idiot who is proceeding without a plan of campaign in his ridiculous and criminal pride.” He ended, “I cannot return home now. My presence is needed here, and besides I have a good deal of property to protect in Paris. Don’t worry about me. I have nothing to fear from anyone.”

Napoléon, 62, surrendered himself — and the French troops accompanying him — to the Prussians on September 2, and the Second Empire collapsed.

Napoleon III Surrenders his Sword, 1870 (Wikimedia.org)

Princess Mathilde (1862), by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photo by Lucy Paquette.

On the night of September 3, 1870, the fifty-year-old Princess Mathilde Bonaparte fled Paris at the insistence of her friends, first heading for Puys, near Dieppe on the English Channel, where her friend, the forty-six-year-old novelist and playwright Alexandre Dumas the younger, offered his home to her. France was proclaimed a Republic on September 4; a provisional French government, the Third Republic, was created, and it deposed Napoléon III on September 4. In the French press, it was rumored that Princess Mathilde had stolen up to 51 million francs in her luggage, and that she had been arrested; it was further alleged that she had stolen diamonds and important paintings from the Louvre. Meanwhile, Mathilde (with two servants) secretly made her way across the French border, to Belgium. By September 12, she had stopped in the first town to she came to — Mons, an hour from Brussels. By October, she wrote, “I am horribly sad and my heart is broken. I remain here, not knowing where to go and not wishing to leave; besides, I really do not care.” She added, “I am sadder than ever; there is nothing left but our complete ruin, and I have not even the hope of better days.” [Mathilde did return to Paris, in mid-June of 1871, and she lived there until her death in 1904 at the age of 83.]

Her former lover, the faithless Comte de Nieuwerkerke, ordered the most valuable paintings removed from Paris on August 30. Convoys from the Louvre left for Brest each day from September 1 to 4. Nieuwerkerke was dismissed by the new government from his post as Superintendent of the Imperial Museums on September 5. It was rumored that he was in prison until he could account for important paintings “which he may have lent to friends.” In reality, Nieuwerkerke – who had been warned of his imminent arrest – fled Paris in September dressed as a valet. He went into exile in England, at Eastbourne. [In April, 1871, Nieuwerkerke sold his home to an American, William Henry Riggs (1837 – 1924) for 188,500 francs and his collection of armor and weapons for 400,000 francs to Sir Richard Wallace (1818 – 1890); it now is part of the Wallace Collection in London. Nieuwerkerke then went to Northern Italy and retired beside a picturesque lake in a luxurious villa at Gattajola, near Lucca, which he bought in May, 1872. He died there in 1892.]

Empress Eugénie, c. 1869-70 (Wikimedia.org)

The forty-four-year-old Empress Eugénie had, with the help of her American dentist, Dr. Thomas Wiltberger Evans (1823 – 1897), escaped incognito to London with a forged passport (and her lady-in-waiting) on September 5. She settled at Camden Place, a secluded estate at Chislehurst, just southeast of London, and was reunited with her only child, the fourteen-year-old Louis Napoléon, Prince Impérial of France. [After six months as a prisoner in Germany, Napoléon III spent the last few years of his life in exile in England with Eugénie and the Prince Imperial, who was killed in the Zulu War in South Africa in 1879. Napoléon III died of kidney disease in 1873; Eugénie, a Spanish countess when she married, lived to the age of 94 and died among her relatives in Spain in 1920.]

In the meantime, while ordinary people were shocked and alarmed, mobs chanting “Vive la République!” and belting out the “Marseillaise” scrawled “Property of the People” across the entrance to the vacated Tuileries Palace and tossed statues of the emperor into the River Seine. They changed street and shop names to obliterate all signs of the despised, now-fallen empire. The avenue de l’Empereur became, with some paint, the avenue Victor Noir. French journalist Victor Noir (1848 – 1870) became a republican hero after being shot by Prince Pierre Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoléon III, in a duel in January. At some point after the Siege of Strasbourg on September 28, 1870 – when General Jean Jacques Alexis Uhrich (1802 – 1886) tried in vain to defend the fortress considered one of the strongest in France — Tissot’s elegant avenue de l’Impératrice (Empress Avenue), the boulevard leading to the recreational grounds at the Bois de Boulogne, was renamed avenue Uhrich.

Although Tissot was too patriotic – or optimistic – to realize it for another eight months, his charmed life in Paris was over forever.

© 2013 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

How much do you know about the Impressionists & War? Take my quiz on goodreads.com!

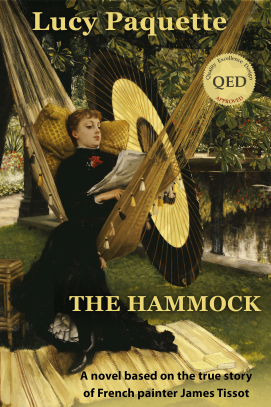

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

And The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot is now available as a print book – a paperback edition with an elegant and distinctive cover by the New York-based graphic designer for television and film, Emilie Misset.

Tissot appears to have been content to live well, contribute wicked caricatures of world figures to a slightly subversive London Society magazine, and maintain a fairly low profile in the art world he had conquered within a decade of his arrival as a provincial art student. Oddly, there are almost no references to Tissot in letters, journals or accounts of his chatty friends and acquaintances during this time, even though his studio was a chic gathering place, and it is likely he visited crowded, gossipy weekly receptions such as those hosted by Princess Mathilde on Fridays and the extremely successful and hospitable painter Alfred Stevens on Wednesdays. It seems that James Tissot was a peaceable and refined gentleman, truly his own man, with all the advantages and disadvantages that accrue to an individual of independent temperament and means in a circle of talented and passionate associates – and rivals – in a world about to implode.

Tissot appears to have been content to live well, contribute wicked caricatures of world figures to a slightly subversive London Society magazine, and maintain a fairly low profile in the art world he had conquered within a decade of his arrival as a provincial art student. Oddly, there are almost no references to Tissot in letters, journals or accounts of his chatty friends and acquaintances during this time, even though his studio was a chic gathering place, and it is likely he visited crowded, gossipy weekly receptions such as those hosted by Princess Mathilde on Fridays and the extremely successful and hospitable painter Alfred Stevens on Wednesdays. It seems that James Tissot was a peaceable and refined gentleman, truly his own man, with all the advantages and disadvantages that accrue to an individual of independent temperament and means in a circle of talented and passionate associates – and rivals – in a world about to implode.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download