To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. Tissot’s last Salon: Paris, 1870. The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/02/05/tissots-last-salon-paris-1870/. <Date viewed.>

On January 2, 1870, the Comte de Nieuwerkerke – the former lover of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte – lost his position of complete control over the arts in France. It was only due to the Princess’ reluctance to see him totally disgraced, after he abruptly ended their twenty-five-year liaison to marry a young girl, that he was not dismissed outright. Napoleon III’s reform-minded new deputy replaced him with a liberal Minister for the Fine Arts, and Nieuwerkerke was demoted from Superintendent of the Fine Arts to Superintendent of the Imperial Museums, under the young Minister.

For Manet, this was invigorating news. Under new rules for the selection of the Salon jury, he campaigned for election but lost. Two of his paintings, however, were accepted for exhibition, held May 1 through June 20, 1870: The Music Lesson (modeled by his friend, the sculptor Zacharie Astruc, 1833 – 1907) and a portrait of his student, Eva Gonzalès.

Portrait of Eva Gonzalès, 1869-1870, by Édouard Manet. The painting she is shown completing here demonstrates the mastery she had achieved at that age. However, this depiction of Gonzales is less than flattering in that her dress, her posture and technique are not actually those of a professional to painting. The painting that Gonzales is working on is not her own, but actually one of Manet’s. It is currently on display at the National Gallery in London. (Photo and caption: Wikipedia)

Manet’s portrait of Eva Gonzalès was called a “flat and abominable caricature in oils.” Other critics said Manet’s paintings were “the most ridiculous things you could imagine,” that his work “provokes only laughter or pity,” and that he was painting “in defiance of art, the public and the critics.” The only encouragement Manet received was, ironically (or perhaps not?) from the critic he had injured in a duel in February over an unflattering review. Now he called Manet “one of the first painters of the age.”

Eva Gonzalès, not quite 21, made her Salon debut in 1870 with three paintings including her take on Manet’s The Fifer (rejected by the Salon jury in 1866). One critic said of Gonzalès’ full-length Little Soldier, “It is an astoundingly strong statement from such a pretty little author” – summarizing the struggle she faced to be taken seriously.

Enfant de troupe (1870), by Eva Gonzalès. Musée Gaston Rapin, Villeneuve-sur-Lot, France (Photo: Wikipedia)

Berthe Morisot, at 29, was extremely unhappy about the place Manet gave Eva in his life and art. She wrote her sister, Edma, “Manet has been lecturing me and sets up that eternal Mademoiselle Gonzalès as an example to me.” As Berthe’s mother was trying to marry her off, Berthe wrote, “I feel sad; I feel alone, disillusioned and old into the bargain.”

The Mother and Sister of the Artist by Berthe Morisot. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Open Access.

Manet did not take her art as seriously as he took Eva’s. Berthe had made her Salon début six years ago, in 1864; at the Salon this year she exhibited The Harbor at Lorient, and The Mother and Sister of the Artist (also called Reading). When she completed Reading in March, she made the mistake of asking Manet’s opinion of it – whereupon he took her brushes and palette and spent hours redoing the mother’s face and black gown. Her mother, standing by, was amused. Berthe, very upset but unable to protest, watched “her” painting carted off to the Salon, where it met with admiration. “The one exception is Degas, who has supreme contempt for everything I do,” Berthe wrote. She, however, appreciated his work, and wrote to her sister Edma, “Degas sent a very pretty painting [Mme. Camus, a brilliant pianist who was the wife of his and Manet’s doctor] but his masterpiece is the portrait of Yves [the eldest Morisot sister] in pastel.”

Madame Camus in Red, by Edgar Degas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Open Access.

Degas’ oil portrait, Madame Camus in Red, received mixed reviews from the critics. This would be the last year Degas exhibited in the Salon: in April, his letter to the Paris- Journal was published, listing numerous specific, logical suggestions on how to improve the exhibition for artists and the viewing public. Since Degas’ name was virtually unknown in the capital, his letter was prefaced by a friend, a sympathetic art critic – the same one whom Manet stabbed in their February duel.

Among the 3,000 canvases exhibited in the Salon of 1870 were paintings by artists well known to Degas and Manet: Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley and the American Mary Cassatt submitted works that were accepted by the jury. Pictures by Monet and Cézanne were rejected. Frédéric Bazille had one painting rejected (La Toilette) and one accepted (Summer Scene (Bathers), 1869).

Other artists, outside their immediate circle, won the prizes. The top prize, the Grand Medal of Honor, went to Tony Robert-Fleury (1837 – 1912), 33, the son of the director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts; his The Last Day of Corinth was, presciently, a brutal scene of the sacking of the Greek city of Corinth by the Romans in 146 B.C.

The Last Day of Corinth, by Tony Robert-Fleury (Photo: Wikimedia)

Twenty-seven year-old Henri Regnault (1843 – 1871), son of the famous chemist and physicist Victor Regnault (1810 – 1878), won the coveted Prix de Rome, for his Salomé, considered a masterpiece of contemporary art.

A great honor – peer adulation – was accorded to Manet, with Henri Fantin-Latour’s painting in the Salon of 1870, A Studio in the Batignolles (Homage to Manet), which was caricatured as Jesus Painting Among His Disciples.

Clustered in admiration around Manet in this painting are the writer and art critic Zola, the young painters Renoir, Monet and Bazille, and the sculptor Astruc – but not the prosperous and accomplished artist James Tissot, whose Salon paintings this year were Young Lady in a Boat/Jeune femme en bateau and Partie carrée/The Foursome, a light-hearted and fully clothed eighteenth-century take on Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (rejected by the Salon jury in 1863).

Young Lady in a Boat, 1870, by James Tissot. Private Collection.

Tissot surely enjoyed the fact that he was the sole painter among his peers from their student days who had achieved success. He seemed to get along well with everyone while steering clear of controversy – a luxury he could not enjoy for much longer.

© 2013 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Watch my new videos:

“The Strange Career of James Tissot” (2:33 minutes)

and

“Louise Jopling and James Tissot” (2:42 minutes)

Partie carrée/The Foursome, 1870, by James Tissot. National Gallery of Canada. (Photo: Wiki)

Exhibition note:

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900

February 17–May 19, 2013 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The first major survey of the art of the Pre-Raphaelites to be shown in the United States features some 130 paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and decorative art objects.

For more information, visit http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/preraphaelites.shtm

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

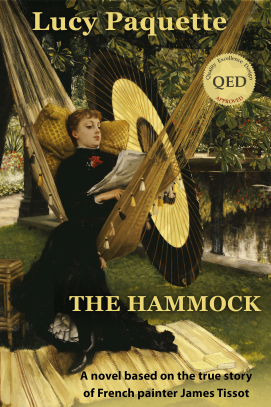

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot is now available as a print book – a paperback edition with an elegant and distinctive cover by the New York-based graphic designer for television and film, Emilie Misset.

Pingback: La Femme à Paris | One quality, the finest.