To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “The Artists’ Rifles, London.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/04/29/the-artists-rifles-london/. <Date viewed.>

Lord Ranelagh at the volunteer gathering in Brighton, 1863. Illustrated London News. (Image: Wikimedia.org)

By the summer of 1859 – as the ambitious 23-year-old Jacques Joseph Tissot, a member of the National Guard in Paris, was making his Salon début under the name James Tissot – the British feared a French invasion under Napoléon III because of an assassination attempt on the Emperor and Empress on January 14, 1858, with bombs made and tested in England by an Italian revolutionary, Felice Orsini (1819 – 1858). A year later, on April 29, 1859, France and the Austrian Empire went to war. On May 12, 1859, the British government authorized the formation of volunteer rifle corps to be called out “in case of actual invasion, or of appearance of an enemy in force on the coast, or in case of rebellion arising in either of these emergencies.” By the end of the year, the volunteer corps comprised thousands of patriotic men all over Great Britain, and was said to be “a force potentially the strongest defence of England.”

The idea of a special corps of artists was conceived by Edward Sterling, an art student and ward of Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle. In May, 1859, Sterling held a meeting at his studio of fellow students in the life class of Carey’s School of Art, Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury. The rooms of artist Arthur Lewis (1824 – 1901) in Jermyn Street became a gathering-place for those who pursued the plan.

The Artists’ Rifles was established on February 28, 1860 as the “The 38th Middlesex (Artists’) Rifle Volunteers.” The Corps met to elect officers at the St. George Street studio of portraitist Henry Wyndham Phillips (1820 – 1868), who became the regiment’s first commander. [Phillips also served for thirteen years as Secretary of the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution, founded in 1814 to assist professional artists in financial distress due to illness, accident or old age.] The regiment initially was headquartered at the Argyll Rooms, a notorious pleasure establishment in Windmill Street, just north of Piccadilly. Members met for preliminary drills in plain clothes, learning the goose step, the “balance-step without gaining ground,” and other rudimentary soldiering skills such as musketry – how to use a ramrod. The government had purchased Burlington House, a Palladian mansion in Piccadilly, in 1854, and the Artists’ Rifles was granted space in it until 1868, when the Royal Academy established itself there. From 1868 until 1889, when members built a permanent headquarters at 17 Duke’s Road, Euston, the Artists’ Rifles met and drilled at various addresses in central London.

The Artists’ Rifles was established on February 28, 1860 as the “The 38th Middlesex (Artists’) Rifle Volunteers.” The Corps met to elect officers at the St. George Street studio of portraitist Henry Wyndham Phillips (1820 – 1868), who became the regiment’s first commander. [Phillips also served for thirteen years as Secretary of the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution, founded in 1814 to assist professional artists in financial distress due to illness, accident or old age.] The regiment initially was headquartered at the Argyll Rooms, a notorious pleasure establishment in Windmill Street, just north of Piccadilly. Members met for preliminary drills in plain clothes, learning the goose step, the “balance-step without gaining ground,” and other rudimentary soldiering skills such as musketry – how to use a ramrod. The government had purchased Burlington House, a Palladian mansion in Piccadilly, in 1854, and the Artists’ Rifles was granted space in it until 1868, when the Royal Academy established itself there. From 1868 until 1889, when members built a permanent headquarters at 17 Duke’s Road, Euston, the Artists’ Rifles met and drilled at various addresses in central London.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, October 7, 1863 (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Founding members of the Artists’ Rifles included painters George Frederic Watts (1817 – 1904), William Cave Thomas (c. 1820 – 1876), William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882), John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896), Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833 – 1898), William Morris (1834 – 1896), Edward Poynter (1836 – 1919), and the 22-year-old Valentine (Val) Cameron Prinsep (1838 – 1904). Members nominated friends as recruits.

James Tissot fled to London in late May or early June of 1871, after serving as a volunteer sharpshooter in the Artists’ Brigade in war-torn Paris. During the decade that Tissot rebuilt his career in England, members of the Artists Rifles included Field Talfourd (1815-1874), portraitist Lowes Cato Dickinson (1819 – 1908), author and critic John Ruskin (1819 – 1900), the German-born painter Carl Haag (1820 – 1915), Ford Madox Brown (1821 – 1893), George Price Boyce (1826 – 1897), Robert Braithwaite Martineau (1826 – 1869), William Wilthieu Fenn (1827 – 1906), portraitist Henry Tanworth Wells (1828 – 1903), John Bagnold Burgess (1829 –1897), Edwin Longsden Long (1829 – 1891), John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (1829 – 1908), Frederic Leighton (1830 – 1896), watercolorist and War Office clerk Joseph Middleton Jopling (1831 – 1884), Arthur Hughes (1832 –1915), George Vicat Cole (1833 – 1893), Henry Holiday (1839 –1927), Charles (Carlo) Edward Perugini (1839 – 1918), Simeon Solomon (1840 – 1905), Marcus Stone (1840 – 1921), Frederick Walker (1840 – 1875), Albert Joseph Moore (1841 –1893), William Blake Richmond (1842 – 1921), Samuel Luke Fildes (1843 – 1927) and his friend Henry Woods (1846 – 1921), Walter William Ouless (1848–1933), and John William Waterhouse (1849 – 1917).

Charles Edward Perugini (1855), by Frederic Leighton (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Frederick Walker (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Robert Braithwaite Martineau (1860) by William Holman Hunt (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Self-portrait, William Holman Hunt (1867) (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Simeon Solomon in Oriental costume, photographed by David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wiki)

Members of the “The St. John’s Wood Clique” – a group of gentlemen painters who resided in that affluent suburb north of London – joined the Artists’ Rifles, including Frederick Goodall (1822 – 1904), Henry Stacy Marks (1829 – 1898), John Evan Hodgson (1831 – 1895), Philip Hermogenes Calderon (1833 – 1898), George Adolphus Storey (1834 – 1919), George Dunlop Leslie (1835 –1921), William Frederick Yeames (1835 –1918) and the photographer who recorded images of many of the artists of his day, David Wilkie Wynfield (1837–1887).

William Frederick Yeames in fancy dress (c. 1860), by David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

George Frederic Watts in fancy costume, by David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Valentine Cameron Prinsep, by David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Self-portrait, David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Sculptors who were members of the Artists’ Rifles included Thomas Woolner (1825 –1892), Charles Bell Birch (1832 – 1893), Thomas Brock (1847 – 1922) and William “Hamo” Thornycroft (1850 – 1925). The regiment also included illustrators and engravers, architects, musicians, vocalists, composers, engineers, actors, authors, journalists, and at least one caricaturist, John Leech (1817 – 1864). Drama critic and author Edward Dutton Cook (1829 – 1883) was a member, as was poet Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837 – 1909). While French-born photographer Camille Silvy (1834 – 1910) lived in London from about 1859 to 1868 and became a member of the Artists’ Rifles, there is no indication that James Tissot joined.

Caricature of Algernon Charles Swinburne, Vanity Fair, November 21, 1874. Caption reads, “Before sunrise.” (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

There were two classes of membership in the Artists’ Rifles: active members enrolled in military service paid an entrance fee of 10s.6d. and an annual subscription of £1.1s., providing their own uniform and firearms (subject to approval of the War Office for the sake of uniformity). Honorary Members were not committed to military service. They paid an additional 10s.6d. entrance fee and an annual subscription of £2.2s. (or a one-time payment of £10.10s.).

Members served with various levels of commitment. In Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens’s Artist Daughter (2006, Doubleday U.K.), author Lucinda Hawksley notes that Carlo Perugini, who joined the Artists’ Rifles in 1860 and served for twelve years, sent the occasional reminder letter to members who missed drill sessions. To be considered active by the government, volunteer riflemen needed to attend eight days of drill and exercise in four months, or 24 days within a year.

Painter William Wilthieu Fenn, who became blind and was grateful for Millais’ kindness and practical assistance in alerting his friends to his inability to earn a living, later recalled that “Millais never quite took to” volunteering. The drills at Wimbledon, where the National Rifle Competition was held, amused Millais, Fenn wrote, “but he tired of it soon, I suspect, and was at any rate very irregular in his attendances.” Millais displayed “a flash of enthusiasm” when rifles were first served out, “but it was not sustained.” Fennn had no memory of Millais ever wearing a uniform: “I don’t think he ever did more than order one, even if he did that. The discipline, loose though it was in all conscience at that date, seemed to irk him; it was not consonant with his painter’s disposition, and besides, it made too long-drawn demands upon his time, hard worker that he was, especially after his family increased as it was rapidly doing by 1860.” Fenn added, “Beyond a few visits to the camp at Wimbledon [in 1861], and a few shots at the targets of various ranges, soldiering did not suit him, and he very soon, I suspect, vanished from the ranks of the active volunteers.” But Millais and fellow rifleman Joe Jopling – who won the Queen’s Prize at Wimbledon in 1861 for his bulls-eye – became great friends during this time.

Officers were drawn from the ranks. Frederic Leighton, who joined on October 5, 1860, was promoted to command A Company within a few months. Henry Wyndham Phillips died in 1868, and on January 6, 1869, Leighton was elected to command the Artists’ Rifles. He was promoted from Captain to Major, and in 1875, he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. Three years later, Leighton was elected President of the Royal Academy, and he resigned as Commanding Officer of the Artists’ Rifles in 1883. [At his funeral in 1896, his coffin was carried into St. Paul’s Cathedral past an honor guard of The Artists’ Rifles.]

Frederic Leighton in Renaissance costume, by David Wilkie Wynfield (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The Artists’ Rifles regimental badge (Photo: artistsriflesassociation.org)

The regimental badge was designed by another member, Leonard Charles Wyon (1826 – 1891), the Queen’s medallist. It depicted the profiles of Mars, the god of War, and Minerva, the goddess of Wisdom. The men recited a regimental rhyme: “Mars, he was the God of war, and didn’t stop at trifles. Minerva was a bloody whore. So hence The Artists’ Rifles.”

Ironically, the “French invasion” from which the Artists’ Rifles were protecting Britain turned out to be artistic, as many painters – including Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro – fled Paris in 1870 and 1871 and sought success in London’s competitive art market. With the exception of French etcher Alphonse Legros (1837 – 1911), who emigrated to England in 1863, married an English girl in 1864, and assimilated easily into British circles, these foreign artists were not exactly welcomed with open arms by the British public nor the close-knit community of painters who bonded in the Artists’ Rifles as well as in London’s many gentleman’s clubs.

In fact, the members of the Artists’ Rifles so enjoyed socializing with each other that, in 1863, they established the Arts Club in a beautifully preserved Adams-style mansion at 17 Hanover Square, richly decorated with carved marble mantelpieces, magnificent oak staircases, and ceilings painted by Angelica Kauffmann, which they dubbed “Sweet Sixteen.”

The Artists’ Rifles served with great distinction in the Boer War and The Great War. The apostrophe was dropped in 1937, when the regiment’s title was officially simplified to “The Artists Rifles.” During the Second World War, the regiment functioned as an Officer Cadet Training Unit, supplying officers to other regiments. The regiment was disbanded in 1945 but was re-established two years later as the Special Air Service Regiment, now the 21 Special Air Service Regiment (Artists) (Reserve).

Bibliography

Chambers’s Journal, sixth series, vol. iv, December 1900 – November 1901 (1901, London and Edinburgh: W & R Chambers Ltd.).

Gregory, Barry. A History of The Artists Rifles 1859–1947 (2006, Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books).

Griffiths, Arthur. Clubs and Clubmen (1907, London: Hutchinson & Company).

Hawksley, Lucinda. Katey: The Life and Loves of Dickens’s Artist Daughter (2006, Doubleday U.K.).

Haydn, Joseph and Benjamin Vincent. Haydn’s Dictionary of Dates and Universal Information Relating to All Ages and Nations (1881: Ward, Lock).

Meynell, Wilfrid, ed. The modern school of art, vol. I (1886-1888, London: W.R. Howell & Company.

Millais, John Guille. The life and letters of Sir John Everett Millais: President of the: President of the Royal Academy, vol. 1 & 2 (1899, London: Methuen).

For more information on The Artists’ Rifles, past and present, see:

Also see Patrick Baty, speaker, writer and self-described “thoroughly good egg and ex-soldier”:

- Facebook page: The artists of The Artists Rifles

- Pinterest board: The artists of The Artists Rifles

- Twitter: @artistsrifles, @MarsMinerva, @patrickbaty

© 2013 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

View my videos, “The Strange Career of James Tissot” (Length: 2.33 minutes) and

“Louise Jopling and James Tissot” (Length: 2.42 minutes).

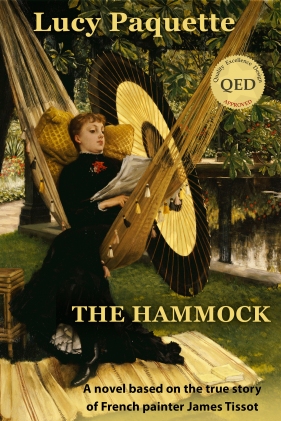

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

_-_Paris,_1871_-_St_Cloud,_La_place.jpg)

_-_Paris,_1871.jpg)

Berne-Bellecour later gained a reputation as a military painter with works like The Tirailleurs de la Seine at the Battle of Rueil-Malmaison, 21st October 1870 (1875).

Berne-Bellecour later gained a reputation as a military painter with works like The Tirailleurs de la Seine at the Battle of Rueil-Malmaison, 21st October 1870 (1875).

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download