To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Others in Tissot’s circle: Morisot, Courbet, Alma-Tadema, Whistler & Millais in 1868.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2012/12/22/others-in-tissots-circle-morisot-courbet-alma-tadema-whistler-millais-in-1868/. <Date viewed.>

Berthe Morisot (Photo: Wikipedia)

James Tissot, handsome and successful at 31, still was unmarried.

In July 1868, the 36-year-old, married Manet was introduced to the elegant and intense 27-year-old Berthe Morisot (1841-95) and her older sister, Edma, who would soon be married. By autumn, Berthe – only sometimes accompanied by her mother – was making regular visits to his studio to model for The Balcony. Of her image in this painting, she later remarked, “I am more strange than ugly.”

Berthe, whose family was wealthy and distinguished, had been painting for a decade. She made her Salon début in 1864 with two landscapes and had exhibited each year, though her work was hung high on the wall and hard to see. The Comte de Nieuwerkerke was the president of the Salon jury in 1868, and he did not care for landscapes any more than he did for the new, modern subject matter infiltrating the Salon walls as never before. Now, four years later, Berthe showed The Pont-Aven River at Roz-Bras, and she was considered a serious enough painter to be noticed in print by Émile Zola.

Courbet exhibited only two pictures at the Salon: Roebuck on the Alert (1867, Musée d’Orsay) and The Beggar’s Alms (Glasgow City Council Museums). But he produced a great many paintings this year, including several nudes: The Woman in the Waves, two versions of a Sleeping Woman, The Three Bathers, The Source, and Nude Reclining by the Sea. Courbet’s 1868 landscapes included The Silent River, Siesta at Haymaking Time, The Bridge at Nahin, The Deer Shelter, and The Stream of The Puits Noir at Ornans.

In addition, Courbet painted a few portraits and illustrated two anti-clerical pamphlets published in Brussels. That summer, he sent eleven pictures, including The Return from the Conference (1863), to an exhibition in Ghent, and he exhibited in Besançon and Le Havre, where he had eight pictures. He also was busy chasing down several of his paintings which had been stolen from various places including London.

Tissot’s Dutch friend Lourens Tadema (later Lawrence Alma-Tadema) exhibited his huge picture, The siesta (No 101) at the Salon in 1868 – because the owner of the one he wished to send, Phidias and the frieze of the Parthenon, Athens (No 104), would not allow it to be shown in public. These were among the forty-eight paintings commissioned in 1867 by Tadema’s agent, Ernest Gambart. Others completed this year including A Roman art lover: (Silver statue) (No 108), Flowers (No 105), and A Birth Chamber, Seventeenth Century.

In London, at the Royal Academy in 1868, Millais exhibited Stella; Rosalind and Celia; A Souvenir of Velasquez; Sisters, a portrait of his three beautiful young daughters, Effie, Mary and Carrie; and Greenwich Pensioners at the Tomb of Nelson (originally titled Pilgrims to St. Paul’s). Effie felt it would be important to posterity to record the details of each of her husband’s paintings over the years, and she had been writing a book since their marriage. But Millais made fun of it, and she reluctantly gave it up this year. Millais spent the autumn shooting in Scotland, as usual, with his friends the new Liberal MP for Oxford Sir William Harcourt (1827-1904), British painter Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-73), and millionaire Underground Railway engineer Sir John Fowler (1817-1898).

As for Whistler, he exhibited nothing in 1868; he was discouraged. When his mother left on a short trip to the United States to visit her family, he took the opportunity to get away from Chelsea to stay with a friend in Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, a more quiet and conducive place to work. However, his friend thought Whistler’s seven-month stay was very unproductive: “His talk about his own work revealed a very different man to me from the self-satisfied man he is usually believed to have been.” Whistler worked hard on several different projects during this time, but did not finish a thing.

Tissot’s mother had died seven years ago, too soon to see her hard-working, talented and ambitious son rising to still greater heights.

© 2012 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

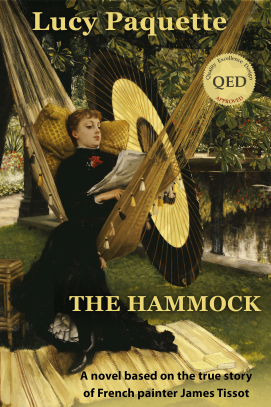

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.