To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot’s garden idyll & Kathleen Newton’s death.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/08/30/james-tissots-garden-idyll-kathleen-newtons-death/. <Date viewed.>

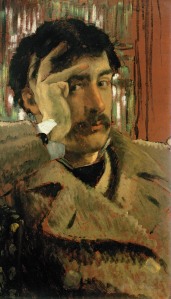

Self portrait (1865), by James Tissot, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA, USA. Courtesy The Bridgeman Art Library

James Tissot fled Paris in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and the bloody Commune early June, 1871, and established himself in the competitive London art market. By March 1872 (and until early 1873), he lived at 73 Springfield Road; he then bought the lease on a medium-sized, two-storey Queen Anne-style villa, built of red brick with white Portland stone dressing, at 17 (now 44), Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood.

The residents of the comfortable suburban homes around the Regent’s Park and the district of St. John’s Wood, west of the park, were merchants, bankers and lawyers. Tissot’s house, set in a large and private garden separating him from the horse traffic, omnibuses and pedestrians on their way to the park or the still-new Swiss Cottage Underground Railway station nearby, was built in 1825 on part of the grounds of the abbey for which Abbey Road was named.

In 1875, Tissot built an extension with a studio and huge conservatory that doubled the size of his house. In the conservatory, he grew exotic plants, while his garden was designed with a blend of English-style flower beds as well as plantings familiar to him from French parks. Gravel paths led to kitchen gardens and greenhouses for flowers, fruit and vegetables.

The Garden, by James Tissot. Geffrye Museum of the Home. Courtesy http://www.jamestissot.org

Tissot improved his garden with the addition of an ornamental pond and a cast iron colonnade, copied from the Parc Monceau in Paris, that ran in a curve from the south side of the pool towards the house. The series of columns, painted black, were rounded except the two at either end, which were square. A similar curved colonnade ran from the east end of the pool.

Quarrelling (c. 1874-76), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart)

The bay window of Tissot’s new studio overlooked this idyllic landscape, which he enjoyed and painted repeatedly, especially during the six years that he shared his home with his mistress and muse, Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly Newton (1854 – 1882). [Click here to see an 1871 London map showing Grove End Road in relation to Hill Road, where Kathleen had been living with her married sister, Mary Pauline “Polly” Ashburnham Kelly Hervey (1851/52 – 1896).]

Study for Mrs. Newton with a child by a pool, by James Tissot. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. (Photo: Wikipaintings)

A Convalescent, by James Tissot. Museums Sheffield. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, by Lucy Paquette, ©2012

The Dreamer, by James Tissot. Musée d’Orsay. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

James Tissot painted Kathleen Newton in the study above [called The Dreamer] in 1878, selling it for £206 as Rêverie at the Dudley Gallery in London. In the 1920s, a man bought it “for a few pounds.” In 1984, the man’s daughter brought the picture to a valuation day at Woodbridge Community Hall in Suffolk, England. She had no idea what it was, but said, “It has been on the wall for as long as I can remember. My dad always used to poke around the sale rooms and this just came home. I can’t remember when. The story always was that he bought it because it reminded him of my mother, they both had the same auburn colored hair. Nobody knew anything about it in the family. We had it re-framed, and while it was at the framer’s somebody offered us £600 for it and so we thought we should get it looked at professionally.” A Sotheby’s representative at the valuation day said, “I remember turning round to say something to my secretary and when I turned back again this gentleman had put the picture down on the table in front of me. I remember taking one look at it and thinking to myself, “My God, a Tissot.”

The 1878 oil study, measuring 11 by 17 in. (27.94 by 43.18 cm), was sold at Sotheby’s, London in 1984) as Rêverie for $ 38,678 USD/£ 32,000 GBP (Hammer price).

There are many stories about the death of Mrs. Newton, including one version in which she threw herself out of the bedroom window and died from her injuries. There is no account of such a suicide in The Times of 1881-82 or inquest lists, according to Tissot’s biographer, James Laver.

Kathleen Newton died of tuberculosis on November 9, 1882, at age 28, at Tissot’s house with her sister, Polly Hervey, at her side (according to the death register). Tissot draped the coffin in purple velvet and prayed beside it for hours. Immediately after the funeral on November 14, at the Church of Our Lady in Lisson Grove, St. John’s Wood, Tissot returned to Paris.

Tissot’s elderly gardener, Willingham, lived with his wife in a small lodge at the end of the garden. Willingham burned Mrs. Newton’s mattress on Tissot’s instructions, but otherwise left everything as it was when Tissot departed: though he took his paintings, all his paints and art supplies remained in trays in the studio. The basement was full of pots containing the materials for Tissot’s cloisonné work. His St. John’s Wood villa remained empty for about a year.

Related posts:

James Tissot’s house at St. John’s Wood, London

James Tissot’s Model and Muse, Kathleen Newton

A visit to James Tissot’s house & Kathleen Newton’s grave

© Copyright Lucy Paquette 2013. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

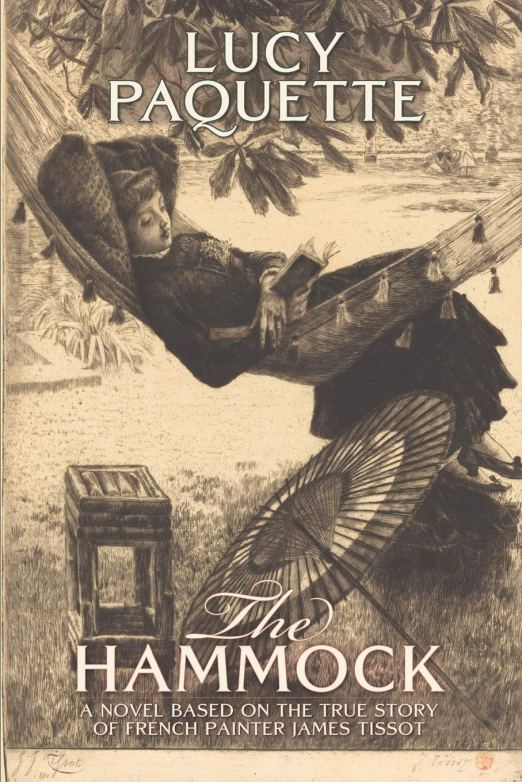

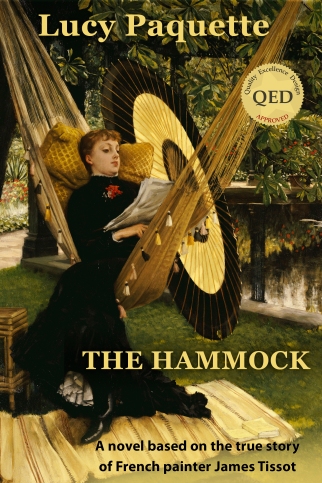

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9).

See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

And The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot is now available as a print book – a paperback edition with an elegant and distinctive cover by the New York-based graphic designer for television and film, Emilie Misset.