To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: Gentlemen & Rogues (1865 – 1879).” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2016/08/11/masculine-fashion-by-james-tissot-gentlemen-rogues-1865-1879/?iframe=true&theme_preview=true. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot, often described as a dandy, seems to have dressed flamboyantly as a young art student in Paris and early in his career.

Self portrait (c. 1865), by James Tissot. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA, USA. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot” by Lucy Paquette, © 2012.

After Tissot found success (in the early 1860s), he began to present himself as a gentleman of business: he wore a frock coat, and there is no indication that he tried to compete with the stylish aristocrats he painted, even as he earned great wealth in his career. In this image, he wears a heavy, tan overcoat with his black frock coat, a cream-colored, high-cut waistcoat, a white shirt with a stand-up collar and notched cuffs, black cuff links, and a plain black tie.

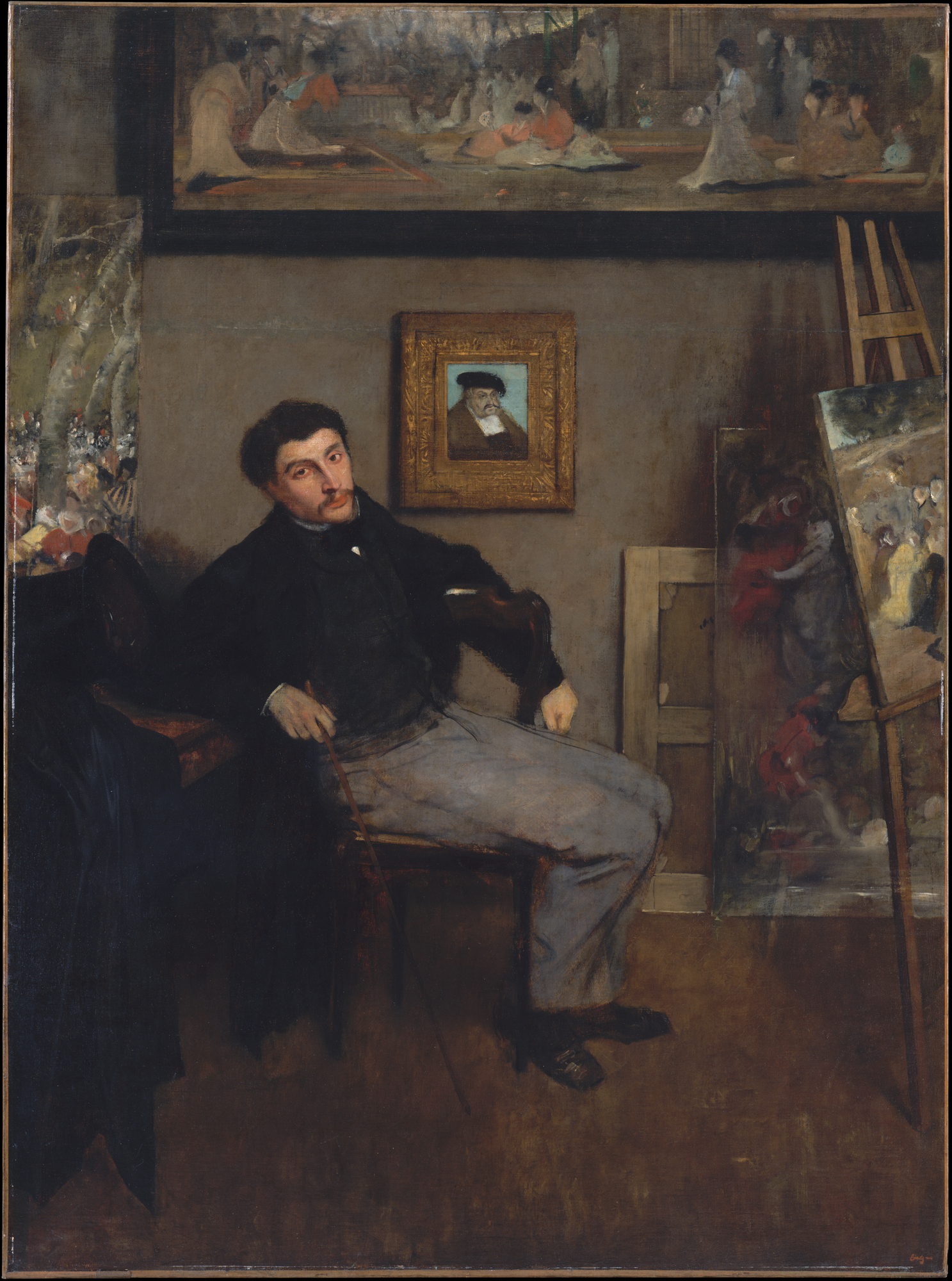

James Tissot (c. 1867-68), by Edgar Degas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Here is Tissot a few years later, in a portrait by Edgar Degas, and while he is well-dressed, he is not wearing anything flashy or trendy. He wears a black frock coat over a dark grey waistcoat and white shirt, with a black cravat, full-cut light grey trousers and black leather half-boots. His black top hat and satin-lined cape are on the table behind him, as if he might be prepared for an evening at the Opera or the theater.

Whether James Tissot was a gentleman or a rogue is debatable. He seems to have fought, however briefly, for the radical Paris Commune in the spring of 1871, before he relocated to London and soon took a young divorcée as his mistress. Though he seems to have tried to help his struggling painter friends, he accumulated great wealth and ended up being considered a rogue by Degas as well as James Whistler and, at times, Berthe Morisot.

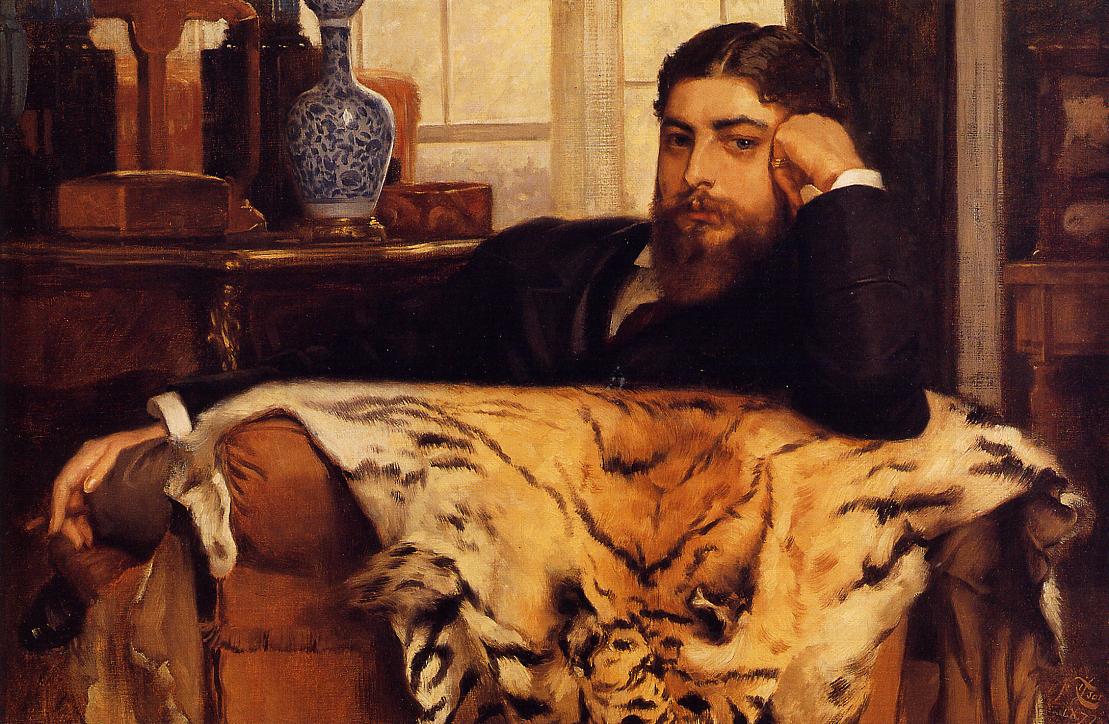

Chichester Parkinson-Fortescue, 1st Baron Carlingford (1823-1898), 1871, by James Tissot (Photo credit: Wikipedia.org)

By all accounts, Chichester Parkinson-Fortescue, 1st Baron Carlingford (1823-1898) was a thorough gentleman. He was a politically ambitious Irishman and Liberal MP for County Louth from 1847 to 1868. He became a junior lord of the treasury in 1854, and in 1863, he married the beautiful, virtuous and politically influential Society hostess Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821 – 1879). Fortescue held minor offices in the Liberal administrations until he was made Chief Secretary for Ireland under Lord Russell from 1865 through 1866, and again under Gladstone from 1868 to 1870. From 1871 to 1874, Chichester Fortescue was President of the Board of Trade.

He was described as pedantic but with a fine intellect. In 1853-54, when Fortescue was a bachelor, John Ruskin often left him alone with his young wife Effie, whom he admired and who apparently confided in him. Fortescue would spend a decade in love with Lady Waldegrave before her elderly husband died; she chose him out of the three or four men who wished to marry her. They were very happy together, as he helped her become more educated, and she used her fortune, charm, and hospitality to further his career. Queen Victoria invited the couple to dine with her at Windsor; she enjoyed Lady Waldegrave’s vivacity and appreciated Fortescue’s pleasant and agreeable manner and gentle voice. He was a diffident man who detested all card games and could only relax in the company of Bohemian types like Edward Lear.

In 1871 Tissot painted Fortescue wearing a black frock coat and full-cut fawn-colored trousers with an elegant white shawl-colored waistcoat, a white shirt with a stand-up collar, and a black tie folded over in a single, loose knot accented with a pearl tie tack. His black leather half-boots shine.

Gentleman in a Railway Carriage (1872), by James Tissot. The Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

This elegant man of business, with his neatly trimmed mustache and beard, spares us a glance as he checks his pocket watch. He is dressed in the latest fashion – a lounge suit: his sack coat, waistcoat, and trousers all are cut from the same fabric. This style was introduced in the 1860s for comfort in the domestic sphere; Tissot’s painting shows that by this date, it was appropriate to wear it in public. The light brown wool is a confident choice that would have set this gentleman apart from the sea of colleagues in black frock coats and also makes the top-stitched edging stand out. His crimson tie and commodious fur-trimmed black overcoat are further evidence that he is a flashy and very successful, individual. Imagine what a figure he’ll cut when he alights from the carriage, wearing the black top hat now at his side, and those white kid gloves, perhaps with the boiled wool blanket folded over his arm as he continues to his destination.

On the Thames (1876), by James Tissot. Hepworth Wakefield Art Gallery, Wakefield, UK. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot” by Lucy Paquette, © 2012.

The Victorians immediately decided this image of a handsome man on an outing with two beautiful women was “More French, shall we say, than English?” Unless the women are the sisters of this junior officer, we might be right to guess that carting them off with a picnic hamper and three bottles of champagne makes him a rogue. He is not in uniform, but wears his black-and-gold naval cap with a loose, thigh-length, single-breasted black wool coat that has wide lapels and upper sleeves, and side vents. He sports off-white trousers with loosely turned-up cuffs, blue socks, and laced, tan-and-white leather spectator shoes with a low heel. Incidentally, Tissot featured the exact same shoes in The Return from the Boating Trip (1873), The Ball on Shipboard (c. 1874), Quarreling (c. 1874-75), and Holyday (c. 1876). Perhaps they were studio props, and certainly they are of more visual interest than the plain black half-boots popular with men at that time.

Algernon Moses Marsden (1877), by James Tissot. Private collection. (Photo credit: Wikimedia.org)

Algernon Moses Marsden (1847 – 1920) was no gentleman.

His father, Isaac Moses (1809 – 1884), owned the Ready-Made Clothing Emporium at Aldgate, and by the time Algernon was 10 years old, the family lived in a grand new house at 23 Kensington Palace Gardens with a bow-fronted ballroom at the back. At 24, Algernon married, but rather than join the family business, he established himself as a picture dealer in St. James’s. In an 1872 trade directory, his residence is listed as Bayswater, a suburb west of London. He may have sold Tissot’s In the Conservatory (Rivals, c. 1875) [see For sale: In the Conservatory (Rivals), c. 1875, by James Tissot], and Marguerite in Church (c. 1860) around 1876, the year he sold William Holman Hunt’s 1866 Il Dolce far Niente through Christie’s, London.

Algernon Marsden lived high and went bankrupt by the age of 34; his debts were settled by his father. Algernon and his wife now resided in Kensington with five young daughters, plus Algernon’s 23-year-old niece, and five servants. When his father died in 1884, he disinherited Algernon in his Will but provided legacies for his wife and children.

In bankruptcy court again in 1887, at 40, Algernon said that when money came in, he “got rid of it” by gambling, particularly at the racetrack, but also at Eastbourne, a fashionable resort. By age 44, he, his wife, nine daughters and one son had moved to South Kensington. Bankrupt for at least the third time, Algernon, at age 54, abandoned his wife and ten children and fled to the United States with another woman in 1901. In 1912, The Times of London reported that Algernon Moses Marsden was bankrupt, but he was living in New York, where he died at the age of 72 on January 23, 1920.

Tissot captured this consummate rogue at age 30, wearing an embellished smoking jacket, a crisp, wing-collared white shirt, and a shining gold ring on his left hand.

The Rivals (I rivali, 1878–79), by James Tissot. Private collection.

There’s no telling if these gentlemen are rogues. Tissot’s The Rivals (I rivali, 1878–79) is set in the conservatory of his home in St. John’s Wood, London. It casts his mistress, Kathleen Newton, as a young widow, crocheting while taking tea with two suitors, one middle-aged and one old. The haughty-looking younger man wears a black sack coat over a white shirt with a stand-up collar, a dark tie, and fawn-colored trousers. The older man, still wearing his gloves, leans forward earnestly in his fully-buttoned, double-breasted black sack coat. Perhaps due his girth, his white waistcoat lines the coat rather awkwardly. His dark blue tie is quite wide, and he wears dark grey trousers and an oddly dainty white boutonnière. Incidentally, while most men of this era simply folded their ties over in a single, loose knot, this man has fastened his with a four-in-hand knot.

The Terrace of the Trafalgar Tavern, Greenwich, London, by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

We can’t suppose these two men are rogues, just because they seem ungentlemanly enough not to interact with the two women in their party. As usual, Tissot depicts an enigmatic situation: these individuals all are waiting for something. The man with the white whiskers and extraordinary matching eyebrows wears a tall grey top hat with a wide black band, which is echoed by his black cravat. He pairs his black frock coat with tan trousers and brown kid gloves. The other man appears to be wearing a black sack coat over his tan trousers. He wears neither hat nor gloves, and shows a bit of an attitude, the way he sits astride the carved chair. Perhaps the two young women are content, not having to converse with the stuffy gentleman nor the unconventional one! Note that Tissot painted this image in 1878, and the lounge suit is not yet so common that either of his male subjects wears it.

Going to Business (c. 1879), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

In this painting, the elderly, wealthy businessman is dressed conservatively in a black frock coat with a starched white shirt front, black cravat, and a black top hat. Victorian viewers snickered that he was off to visit his mistress. Gentleman or rogue?

Related posts:

Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: Aristocrats (1865 – 1868)

Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: Officers, soldiers & sailors (1868 – 1883/85)

Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: The Casual Male (1871 – 1878)

Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: Sportsmen & Servants (1874 – 1885)

© 2016 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.