To cite this article, Paquette, Lucy. “Portrait of the Pilgrim: “a dealer of genius” (1899-1900).” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2019/04/15/portrait-of-the-pilgrim-a-dealer-of-genius-1899-1900/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot, having devoted years researching and completing his Life of Christ illustrations, did not leave his reputation to his friends.

The Sermon of the Beatitudes (La sermon des béatitudes, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

In March, 1899, an eleven-page article on Tissot and his Christianity and art appeared in McClure’s Magazine. Written by Cleveland Moffett, a 36-year-old American journalist, the article was based on personal interviews with the artist, now 62, over several weeks.

It begins with a long shot of Tissot’s lone figure on a cliff, standing in rugged travel garb with his hands at his hips, surveying a vast desert landscape, over the caption, “The Place where the Sermon on the Mount was Pronounced” – along with a reproduction of Tissot’s watercolor, The Sermon on the Mount (right), showing the same landscape, this time crowded, with Jesus standing on the spot where Tissot was photographed. The awestruck Moffett extols Tissot’s “vigor” and describes him at the outset: “the spiritual quality in this distinguished artist is one of his most striking characteristics. Not only is he deeply religious in his daily life, but he is something beyond that: he is a mystic and a seer of visions.”

The Procession in the Streets of Jerusalem (Le cortège dans les rues de Jérusalem, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

Moffett described Tissot’s earlier career, supplanted by his new religious fervor: “And now in the East a star of guidance shone out clear, a sign in the heavens beckoning this man, calling him to Jerusalem, and he heard the call and answered it.”

Moffet recorded Tissot’s anecdotes of his travels. In November, 1886, approaching Jerusalem in the rain, Tissot reprimanded the guide for suggesting a short cut: “Do you think I have traveled two thousand miles to have my first impression spoiled? Do you think I have come here like a scampering tourist?”

Tissot also told Moffett how he painted his pictures – and that “many of his best pictures were never painted at all, because the very gorgeousness of the scene made it slip from him as a dream vanishes, and it would not come back. ‘Oh,’ he sighed, ‘the things that I have seen in the life of Christ, but could not remember! They were too splendid to keep.’”

What Our Lord Saw from the Cross (Ce que voyait Notre-Seigneur sur la Croix, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

In 1900, Tissot entered into partnership with the McClure Company of New York to publish The Life of Christ, previously published in New York by L. Weiss & Co. (1896-97) and Doubleday (1898).

Tissot’s talent for publicizing his piety while monetizing his Christianity did not sit well with some of his friends.

Edmond de Goncourt, a cynical observer of those around him and whose novel, Renée Mauperin (1884), Tissot had illustrated, did not find him credible; Goncourt wrote in his journal in January, 1890, “Tissot, this complex being, with his mysticism and cunning, this intelligent worker, despite his unintelligent skull and his eyes of a cooked whiting, was passionate, finding every two or three years a new passion, with which he contracted a new little lease on his life.”

Edgar Degas, once one of Tissot’s closest friends, had a different reaction to his success: fury. He wrote in a letter to Ludovic Halévy, “Now he’s got religion. He says he experiences inconceivable joy in his faith. At the same time he not only sells his own products high but sells his friends’ pictures as well…To think we lived together as friends and then…Well, I can take my vengeance. I shall do a caricature of Tissot with Christ behind him, whipping him, and call it Christ driving His Merchant from the Temple. My God!”

The Merchants Chased from the Temple (Les vendeurs chassés du Temple, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

The Bad Rich Man in Hell (Le mauvais riche dans l’Enfer, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

While Tissot was not alone in selling works bought from Degas or received from him as gifts, he did sell at least two. In 1890, Tissot sold Degas’ Horses in a Meadow (1872) for an unknown amount to art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who kept it until his death in 1922. Durand-Ruel actually had purchased the picture from Degas in 1872 and sold it in January, 1874 for under 1,000 francs to Paris opera baritone Jean Baptiste Faure (1830-1914). Faure returned it to Degas, who gave it as a gift to James Tissot. Several years later, on January 11, 1897, Tissot sold a painting that Degas had given him as a gift in 1876, right after finishing it – a portrait of a woman named Lyda, titled Woman with Binoculars. Tissot received 1,500 francs from Durand-Ruel for the picture; Durand-Ruel sold it to H. Paulus that November for 6,000 francs. After keeping the picture for over twenty years, why did Tissot sell it – especially for a mere 1,500 francs when it was worth four times that? [Tissot sold Manet’s Blue Venice in 1891, possibly at a profit, after Manet’s 1883 death had made his work valuable; he bought it on March 24, 1875 for 2,500 francs, after the two painters had traveled to Venice together, and Manet badly needed the income.]

Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray (Jésus monte seul sur une montagne pour prier, 1886-1894), by James Tissot. Watercolor. Brooklyn Museum. (Wikimedia.org)

But any profit realized by the sale of these paintings paled in comparison to the income the French painter in the English business suit was earning from his own work.

In 1900, at the end of the North American tour, James Tissot’s Life of Christ water-colors and pen-and-ink drawings were purchased by the rapidly expanding Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, now the Brooklyn Museum, as advised by the painter John Singer Sargent. Sargent referred to Tissot as “a dealer of genius,” but the museum’s trustees wanted to attract the crowds that flocked to Tissot’s exhibitions.

Tissot set the price for these 540 works – he refused to allow them to be sold separately – at the substantial price of $60,000. The money was raised by public subscription.

According to the museum’s website, “Every two or three days, newspaper headlines in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle urged the borough to ‘Bring the Tissot Pictures Here.’ The Eagle published the names of the donors and the amounts they had pledged toward the acquisition, which the paper described as ‘the most important contribution to the knowledge of the life of Christ that has been given to mankind in the form of art since the creations of the great masters of the Italian, Spanish and Dutch schools of painting.’” Subscriptions flowed in at the rate of $300 – $1,000 per day for several months.

In 1992, the Brooklyn Museum acquired a sketchbook of studies Tissot made during his research trips to the Middle East.

Tissot’s Life of Christ illustrations, not currently on view, were last exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum in 2009-2010.

© 2019 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related posts:

Portrait of the Pilgrim: James Tissot’s Reinvention (1885-1895)

Portrait of the Pilgrim: “not necessary or advisable to start a controversy” (1896-1898)

James Tissot the Collector: His works by Degas, Manet & Pissarro

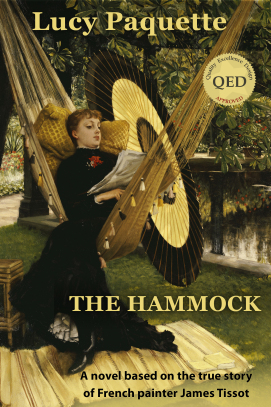

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

The Exposition Universelle was held in Paris from April 14 to November 12, 1900, and nearly fifty million people visited it.

The Exposition Universelle was held in Paris from April 14 to November 12, 1900, and nearly fifty million people visited it.