To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot Domesticated.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2015/05/15/james-tissot-domesticated/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot’s tense, moody oil paintings from the mid-1870s gave way to straightforward scenes filled with the contentment of domestic life, during the few years of Tissot’s life in which he could enjoy a household of children.

For six years, he shared his home with his much younger mistress and muse, Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly Newton (1854 – 1882). Kathleen, a divorcée, previously had been living with her married sister, Mary Pauline “Polly” Ashburnham Kelly Hervey (1851/52 – 1896), around the corner at 6, Hill Road.

[Click here to see an 1871 London map showing Grove End Road in relation to Hill Road.]

On March 21, 1876, Kathleen’s son, Cecil George Newton, was born at 6, Hill Road. Her daughter, Muriel Violet Mary Newton, was four, and her sister, Polly Hervey, had two daughters, three-year-old Isabelle Mary (“Belle”) and one-year old Lilian Ethel (“Lily”).

According to legend, Tissot met Mrs. Newton while posting a letter. She moved into Tissot’s large home at 17 (now 44), Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood (west of Regent’s Park) about 1876.

Study for “Mrs. Newton with a Child by a Pool” (c. 1877-78), by James Tissot. Oil on mahogany panel, 12 ¾ by 16 ¾ in. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), Richmond, Virginia. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Study for “Mrs. Newton with a Child by a Pool” (c. 1877-78) depicts Mrs. Newton by the ornamental pool in Tissot’s garden. The oil painting that resulted from Tissot’s study, Mrs. Newton with a Child by a Pool (1878) is in a private collection. At auction at Christie’s, London in 1995, the Lot Notes read, “In this oil sketch, possibly made from life, [Kathleen Newton] is seen in the garden of the house in Grove End Road, presumably with the son [born Cecil George Newton, 1876; died Cecil Ashburnham, 1941] she had by either Tissot or a previous lover.”

Hide and Seek (1877), by James Tissot. 28 7/8 by 21 1/4 in. (73.4 by 53.9 cm). The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, by Lucy Paquette © 2012

Hide and Seek (1877) shows Mrs. Newton relaxing with a newspaper in Tissot’s studio, which looked out on his extensive garden, while her children and nieces play.

Reading a Story (c. 1878-79), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Reading a Story, c. 1878-79, captures Kathleen Newton in a private moment with her niece, Lilian Hervey.

Uncle Fred (Frederick Kelly with his niece Lilian Hervey, 1879-80), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 7 by 12 in./17.78 by 30.48 cm. Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Kathleen Kelly’s marriage to Dr. Isaac Newton, a surgeon in the Indian Civil Service, had been arranged by her older brother, Frederick Kelly. The ceremony took place on January 3, 1871, when she was seventeen, and the marriage ended in divorce within months. Mrs. Newton returned to England and gave birth to Violet at the end of the year. Tissot painted Uncle Fred (Kathleen Newton’s brother, Frederick Kelly, with his niece Lilian Hervey in 1879-80, and he kept it until his death in 1902. His own niece, Jeanne Tissot, who lived in France, kept this painting until her death in 1964, after which it was sold. Andrew Lloyd Webber purchased the painting at Sotheby’s, New York in February, 1994.

Quiet (c. 1881), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 13 by 9 in./33.02 by 22.86 cm. Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Quiet (c. 1881) shows Kathleen reading a story to her niece, Lilian Hervey, on another day (probably closer to 1879-80) in Tissot’s garden. Quiet was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1881. It was purchased by Richard Donkin, M.P. (1836 – 1919), an English ship owner who was elected Member of Parliament for the newly created constituency of Tynemouth in the 1885 general election. The small painting remained in the family and was kept in perfect condition. It was a major discovery of a Tissot work when it appeared on the market in November, 1993, and it was purchased by Andrew Lloyd Webber at Christie’s, London for $ 416,220/£ 280,000.

Incidentally, it was Lilian Hervey who, at age 71 in 1946, publicly identified “La Mystérieuse” – the Mystery Woman who so often appeared in Tissot’s work – as her aunt, Kathleen Newton, when a reporter published a request for information.

Kathleen Newton at the Piano (c. 1881), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 44 by 30 in. (111.76 by 76.20 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Around 1881, Tissot painted Kathleen Newton at the Piano. Her son, Cecil, now about age five, stands at her left. The tall girl behind him is probably his sister, Violet, now about ten, and the girl on the right is probably his cousin, Belle, now about eight.

In 1989, Kathleen Newton at the Piano was sold at Sotheby’s, New York for $ 400,000/£ 228,480.

Just seven years later, in 1996, the picture was sold at the same auction house for $ 200,000/£ 125,620.

En plein soleil (In the Sunshine, c. 1881), by James Tissot. Oil on wood, 9 3/4 by 13 7/8 in. (24.8 x 35.2 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

En plein soleil (c. 1881), shows Kathleen Newton (in the left hand corner) in the garden of Tissot’s home in St. John’s Wood. The woman seated on the brick wall is either Kathleen’s sister, Polly, or Kathleen’s doppelgänger, in a composite picture. Cecil, shown in his brown suit, would have been about five. Polly had a son, Arthur Reginald (“Bob”) Hervey, in March, 1878, who may be the child under the parasol. The girl in pink is possibly Kathleen’s niece, Lilian Hervey, around age six.

A Children’s Party (c. 1881-82), by James Tissot. 32.4 by 24.1 cm. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

A Children’s Party (c. 1881-82), shows a family celebration in Tissot’s garden. The woman in the foreground, serving tea, is probably Polly Hervey, with Cecil George seated near her. Kathleen is in the background, on the left.

Le Petit Nemrod (A Little Nimrod), c. 1882, by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34 ½ by 55 3/5 in. (110.5 by 141.3 cm). Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’archéologie, Besançon, France. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Le Petit Nemrod (A Little Nimrod, c. 1882) depicts cousins, the children of Mrs. Newton and her sister Polly Hervey, playing together in a London park. (Nimrod, according to the Book of Genesis, was a great-grandson of Noah, and he is depicted in the Hebrew Bible as a mighty hunter.)

Le banc de jardin/The Garden Bench (1882), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 99.1 by 142.2 cm. Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Le banc de jardin/The Garden Bench (c. 1882) was a favorite image of Tissot’s; he kept it all his life. Pictured are Kathleen Newton, her daughter Violet, her son Cecil George, and a second girl who could be her niece Lilian Hervey or her niece Belle (behind the bench).

American millionaire Frederick Koch (b. 1933) began collecting Victorian paintings in the 1980s. Tissot’s Le banc de jardin (The Garden Bench) set an auction price record in 1983, when Fred Koch paid $ 803,660/£ 520,000 for it at Christie’s, London. In October, 1994, Le Banc de jardin set another record for a Victorian picture – as well as a record to date for a Tissot painting – when Lloyd Webber purchased it from Fred Koch for $ 4,800,000/£ 3,035,093 at Sotheby’s, New York.

When Kathleen Newton died of tuberculosis on November 9, 1882, the happy family life Tissot had depicted for six years ended immediately. Tissot remained in London only long enough to attend Kathleen’s funeral. He then moved to Paris and lived in France for the final twenty years of his life.

According to Tissot scholars David S. Brooke (b. 1931), Michael Wentworth (1938 – 2002), and Willard E. Misfeldt (b. 1930), Kathleen’s daughter, Violet, and her son, Cecil George, spent the next two years with their aunt, Polly Hervey, at 6, Hill Road. Violet, after being educated in a convent in Belgium, became a governess in Golders Green, a London suburb.

Cecil George became an army captain. Before he turned twenty, he contacted the man named as his father on his birth certificate – Dr. Isaac Newton. Though Cecil was rejected, he later made a claim on Dr. Newton’s estate that proved futile. Violet also made a claim on Dr. Newton’s estate. She won on a legal technicality and was granted a settlement of £ 10,000.

James Tissot, who died in 1902, left Violet and Cecil each 1,000 francs in his Will. A servant located their addresses, which indicates that Tissot had not been in touch with them in his final years.

Cecil married in 1904, at age twenty-eight, an actress named Florence Tyrrell. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Artillery during the Great War and was discharged as an invalided officer in 1916. He and Florence divorced in 1924. My research indicates that Florence Tyrrell had a steady career performing in comedies on the London stage for over twenty-five years.

Violet, at the age of fifty-four in 1925, married William Henry Bishop in London and died of a heart attack in Spain at age sixty-two.

That same year – 1933 – at the first retrospective exhibition of James Tissot’s work at the Leicester Gallery, London, Cecil made a bit of a scene by standing before the paintings of Tissot’s mysterious muse and announcing, “That was my mother!” before making a quick exit. Cecil died as Cecil Ashburnham in 1941, at age sixty-five in Lancing (a town on the English Channel, near Brighton). Cecil left no Will, but his estate, valued for probate at £108.12s.6d, was administered by George Ashburnham Newton, of Llandudno, a seaside town in Wales.

Related posts:

James Tissot’s house at St. John’s Wood, London

James Tissot’s garden idyll & Kathleen Newton’s death

Was Cecil Newton James Tissot’s son?

A visit to James Tissot’s house & Kathleen Newton’s grave

James Tissot in the Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection

© Copyright Lucy Paquette 2015. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

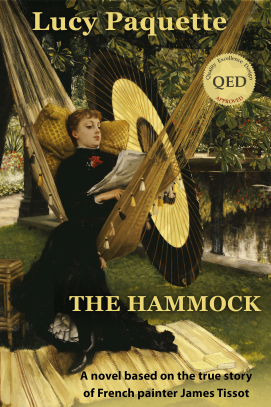

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9).

See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.