To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot’s Brushwork.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2018/11/15/james-tissots-brushwork/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot was an individualist whose style and brushwork was neither entirely Academic, according to his training, nor always fashionable, though some of his oil paintings feature looser, more Impressionistic brush strokes. Though he did not establish trends, he absorbed them into his repertoire and transmuted them into a virtuoso formula all his own.

James Tissot was an individualist whose style and brushwork was neither entirely Academic, according to his training, nor always fashionable, though some of his oil paintings feature looser, more Impressionistic brush strokes. Though he did not establish trends, he absorbed them into his repertoire and transmuted them into a virtuoso formula all his own.

Tissot, who left his parents’ home in Nantes and moved to Paris in 1856, enrolled at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in March, 1857. He was 20 years old, and his classes would have included mathematics, anatomy and drawing, but not painting. He studied painting independently under Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1809 – 1864) and Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869), both of whom had been students of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867) and taught his principles. [See On his own: Tissot as a Paris art student, 1855 — 1858.]

He made his début at the Paris Salon in 1859, and hit his stride as an artist by the Salon of 1864, with The Two Sisters and Portrait of Mademoiselle L.L. In his self-portrait the following year – nine years before his friends joined together to exhibit paintings in a style that would be called “Impressionism” – which was not displayed in public, Tissot delineated his features and clothing in ultra-modern, swift, painterly brush strokes against a minimalist, sketchy background.

But when he received private commissions for portraits of French aristocrats during the Second Empire, he combined his mastery of high finish with his consummate confidence in making his most adroit brush strokes visible.

One of the foremost examples of Tissot’s remarkable brushwork is the ruffled edging of the pink peignoir in Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866).

The ruffles, which appear so precise, are graceful, curling strokes of a loaded, round brush. The folds of the silk velvet dressing gown are thick broad swathes of color, underscored by a right-to-left flutter of white that creates the petticoat peeking underneath. Zoom in on all the luscious detail here.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, unframed: 50 1/2 by 30 3/8 in. (128.3 by 77.2 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1867), a series of a half-dozen thick white curves defines the convex glass cover of the clock’s face. Rather brilliantly, they are flanked by white in the background and in the foreground – on the left, the lightly-suggested white, back-lit curtains dressing the window reflected in the mirror over the mantel, and on the right, the bold white of shapes of Fontenay’s collar and waistcoat. Using his brush to apply white paint in different ways, Tissot has defined three-dimensional space on his canvas.

In Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1867), a series of a half-dozen thick white curves defines the convex glass cover of the clock’s face. Rather brilliantly, they are flanked by white in the background and in the foreground – on the left, the lightly-suggested white, back-lit curtains dressing the window reflected in the mirror over the mantel, and on the right, the bold white of shapes of Fontenay’s collar and waistcoat. Using his brush to apply white paint in different ways, Tissot has defined three-dimensional space on his canvas.

Portrait of Eugène Coppens de Fontenay (1867), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 27 by 15 in. (68.58 by 38.10 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Photo: Wiki)

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870) are riveting when viewed at close range.

The perfectly placed dry brush strokes that Tissot used to define the volume of Gus Burnaby’s black leather boots and give them their astonishing gleam in Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870) are riveting when viewed at close range.

This painstakingly-detailed portrait was another private commission, this time from a friend in London, his home from mid-1871 to late 1882.

Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870), by James Tissot. 19.5 by 23.5 in. (49.5 by 59.7 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The seated woman’s flowing hair in Autumn on the Thames (1875) is one of the most enchanting details in Tissot’s work. With the lightest of touches from his brush, he has made us feel the river breeze as it ripples through her ethereal locks.

Though the figures are highly finished and the palette is that of an Academician, note the looser style in which Tissot painted the water, grass and background landscape.

This picture was not exhibited in public.

Autumn on the Thames, Nuneham Courtney, by James Tissot. 29 by 19 in. (73.66 by 48.26 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

More in the style of his friends in Paris were two other paintings that Tissot did not exhibit, On the Thames, A Heron (c. 1871-72) [figure a] and The Fan (c. 1875) [figure b]. While the figures and their costumes are completed to a high finish and both are painted in a studio rather than en plein air, the landscape backgrounds are rendered in brisk, suggestive strokes, and there is a new sense of movement. Click here to zoom in on Tissot’s brushwork in On the Thames, A Heron, and pay particular attention to the rippling water and the heron; also see A Closer Look at Tissot’s “The Fan”.

a  b

b

Tissot remained, at heart, a painter in the Academic tradition; he was not an Impressionist, concerned with the shifting effect of natural light, vivid colors, and capturing the fleeting experiences of contemporary life as they did. The Japanese influence in these two paintings is what makes them contemporary. But as a Frenchman who had emigrated to England after the bloody Paris Commune [see Paris, June 1871], he hardly could have entered canvases painted in “the modern French style” to the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy.

The Bunch of Lilacs (c. 1875), one of two paintings he exhibited at the Royal Academy that year, was more conservative. Tissot conjures the reflection of a dense array of vegetation and Oriental accessories on a foreshortened grid of decorative tile. His sure brush creates the ultimate polished floor as a stage for this carefree bird of paradise.

The Bunch of Lilacs (c. 1875), by James Tissot. 21 by 15 in. (53.34 by 38.10 cm). Private Collection. Image courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot,” by Lucy Paquette © 2012

Hush! (The Concert, 1875), the second picture Tissot exhibited at the Royal Academy that year, also was highly finished. Note how he painted the chandelier’s multitude of glittering, highly-defined crystal pendants quite differently when reflected in the mirror.

Hush! (The Concert, 1875), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas; 29.02 by 44.17 in. (73.7 by 112.2 cm). Manchester Art Gallery, U.K. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Holyday (c. 1876) was one of several paintings Tissot exhibited in 1877 at the exclusive, innovative new Grosvenor Gallery, for which he eschewed his regular showings at the Royal Academy.

Tissot turned the dark shape of the pond into shining water by deft white strokes (as well as floating lily pads) defining the surface, and reflections of the man, woman, tree and cast-iron columns in the background implying its depth. This treatment of the water, as well as the background of the picture space, is far more finished than that in Autumn on the Thames. At the same time, Tissot now was, or was giving the impression of, painting en plein air.

Holyday (c. 1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 30 by 39 1/8 in. (76.5 by 99.5 cm). Tate Britain. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See A Closer Look at Tissot’s “Too Early”.]

Tissot was masterful in his ability to paint the sheer fabrics of women’s attire. The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (1877) was one of Tissot’s exhibits at the new Grosvenor Gallery. In his review of this picture, the critic for The Spectator commented, “We would direct our readers’ attention to the painting of the flesh seen through the thin white muslin dresses, in this picture; manual dexterity could hardly achieve a greater triumph.” Regardless of Tissot’s skill with the brush, that compliment followed the acerbic observation, “That the ladies are ‘Parisienne,’ dressed in the height of the prevailing fashion, goes without saying, for M. Tissot, though he paints in England, has a thorough Parisian’s contempt for English dress and beauty, and the only time he attempted to paint English girls (in his picture of the ball-room at the Academy [i.e. Too Early, 1873]), he made them all hideous alike.” [See A Closer Look at Tissot’s “Too Early”.]

The Gallery of the HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth), c. 1876, by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 27 by 36 1/8 in. (68.5 by 92 cm). Tate, London. (Photo: the-athenaeum.org)

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

In Evening (Le Bal, 1878), the cascade of layered ruffles is a tour de force of Tissot’s ability to define precise, minute folds of fabric, shaded and highlighted and juxtaposed with contrasting trim in related hues. His lively brushwork lets us feel the volume, weight, and movement of that train.

When Tissot exhibited this painting at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1878, the reviewer for The Illustrated London News was only begrudgingly moved: “’Evening,’ which may be termed at once an ‘arrangement in yellow’ and a glorified excerpt from a Book of the Fashions, [is] brimful of verve, elegance and manual dexterity…Society, we conceive, ought to be very much obliged to so deft an expositor.”

Le Bal/Evening (1878), by James Tissot. 35 7/16 by 19 11/16 in. (90 by 50 cm). Musée d’Orsay. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The highly accomplished French painter succeeding wildly in London despite the British critics carried on, experimenting with brush techniques while staying true to his Academic background.

In A Winter’s Walk (1878), Tissot painted the fur and the foliage in quick, overlapping strokes of varied hues, dragging out the color of the fur with a stiff, dry brush to indicate its soft texture while blurring the edges of the greenery to indicate its rough texture and its distance in the background. He rendered the rich, heavy dress fabric by laying on tints and shades of color with a broad brush, and he enlivened the sober palette with a flash of gold in the captivating detail of Kathleen Newton’s pair of gold bracelets. Tissot’s painterly glint on the smooth bangle and expertly-applied highlights on the rope cuff make this jewelry an exquisite focal point of her costume, all the more solid with the juxtaposition of the sketchily outlined, diaphanous trim peeking from her sleeve.

This picture was not exhibited in public.

A Winter’s Walk (Promenade dans la neige) (c. 1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 31.10 by 14.57 in. (79.00 by 37 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

In A Type of Beauty (1880), Kathleen Newton’s black lace mitts are delicately painted over her flesh with a small brush. The curves of the rope cuff bracelets, flecked with gold highlights, and the further curves of two layers of wispy white ruffles, keep the volume of her forearm from being flattened out by Tissot’s exacting depiction of the lace’s fine pattern.

But Mrs. Newton’s shining curls – just as fine – are loosely described using a soft brush that repeats the highlights of the gold bracelet.

The texture of the trim at her sleeve was created with a stiff, square brush whose bristles barely traced the white paint.

A Type of Beauty (Portrait of Kathleen Newton, 1880), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 23 by 18 in. (58.42 by 45.72 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

James Tissot excelled at accurate depictions and descriptive brushwork; he was not an innovator like his friends Edgar Degas, Edouard Manet and James Whistler. Though his style has been unfavorably compared to theirs over the decades, Degas once considered him far more skilled. In 1868, Tissot left copious technical notes for Degas on how to improve one of his paintings-in-progress, Interior (The Rape), at Degas’ apparent request; clearly, this was the relationship they had. Tissot knew what he was doing, and some found his artistic confidence irritating: one critic at this time observed that Tissot was dapper and personable, but thought him a little pretentious and a less-than-great artist “because he did what he wanted to do and as he wished to do it.”

And he was successful at it: Tissot’s brushwork, in addition to his subject matter and composition, continues to delight and draw us into his paintings. Who could ask for more?

Related posts:

James Tissot, the painter art critics love to hate

Tissot’s Brush with Impressionism

Tissot and Manet attempt to help their friend Degas, 1868

Was James Tissot a Plagiarist?

More “Plagiarists”: Tissot’s friends Manet, Degas, Whistler & Others

© 2018 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

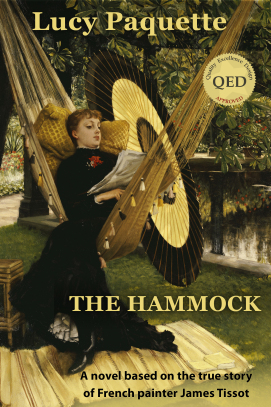

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYV