To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot’s Modern Paintings in Victorian England.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2018/07/15/james-tissots-modern-paintings-in-victorian-england/. <Date viewed.>

French painter James Tissot emigrated from Paris to London in mid-1871, in the chaos after the Franco-Prussian War and bloody Commune, and became successful in Victorian England within a few years. In 1873, he sold Too Early through London art dealer William Agnew (1825 – 1910) – who specialized in “high-class modern paintings” – for 1,050 guineas. Agnew purchased The Ball on Shipboard from Tissot the following year, and in 1875, purchased Hush! directly from the wall of the Royal Academy by for 1,200 guineas.

What made Tissot’s paintings “modern”? How were his pictures of everyday life different from those painted by his English contemporaries?

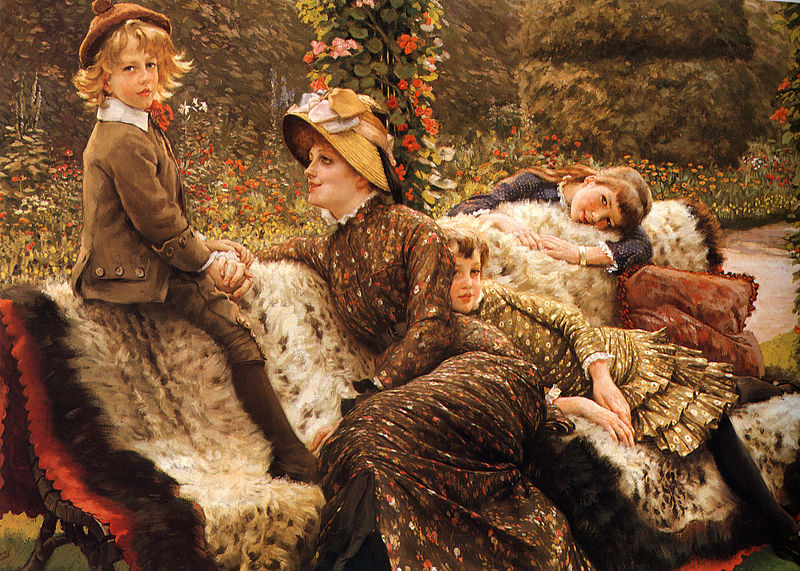

James Tissot (1836 – 1902), an astute businessman keenly aware of buyers’ preferences, painted many subjects that his English contemporaries did. But while Victorian painters like George Dunlop Leslie (1835 – 1921) depicted genteel women behaving well – docile and proper – Tissot was a bit daring. Like others, he also painted a woman (his mistress and muse, Kathleen Newton) reading – but his model is a bit of a rebel, wearing eye makeup and a gown with a revealing neckline, improper as a day dress. In Her Favorite Pastime, Leslie presents us with a straightforward rendering of a pretty and sedate woman focused on her book. In Tissot’s Quiet, Kathleen is sitting – quite indecorously – with her legs crossed, somewhat slumped forward, against a racy leopard skin. Yet, the image is of a loving mother, the exhausted girl leaning lovingly against her, and the resting dog underscores the domesticity of the scene while the expansive green lawn behind them indicates the wealth of the household.

Left: Her Favorite Pastime (1864), by George Dunlop Leslie

Right: Quiet (c. 1881), by James Tissot

While his English contemporaries depicted the ideal of contented domestic life, with family members often in stiffly posed compositions, Tissot’s showed a casual reality. George Goodwin Kilburne’s The Piano Lesson relies on the single child obediently taking instruction and a symmetrical composition to show us the orderliness of this family’s conduct. In Kathleen Newton at the Piano, Tissot gives us a peek behind the curtain dividing the formal front parlor from the informal room behind, where Kathleen, her two children, and an older niece huddle affectionately near her as she plays for them.

Left: The Piano Lesson (1871), by George Goodwin Kilburne

Right: Kathleen Newton at the Piano (c. 1881), by James Tissot

In A Mother’s Darling, Kilburne depicts the girl as a little woman; in The Garden Bench, Kathleen Newton’s son, daughter and niece are children behaving spontaneously.

Left: A Mother’s Darling (1869), by George Goodwin Kilburne

Right: The Garden Bench (c. 1882), by James Tissot

The four pictures of afternoon tea below, two by Leslie and two by Tissot, illustrate Leslie’s literal manner and Tissot’s rather racy take on this British ritual. While Leslie’s lone ladies are being served by a housemaid and dreaming wistfully into the distance, Tissot’s social beings are using the occasion to flirt and sum up available suitors.

Left: Afternoon Tea (1865), by George Dunlop Leslie

Right: In the Conservatory (Rivals, c. 1875), by James Tissot

Left: Five o’Clock Tea (c. 1874), by George Dunlop Leslie

Right: The Rivals (I rivali, 1878–79), by James Tissot

Below, in Alice in Wonderland, Leslie depicts an iconic family moment as a mother stimulates the imagination of her daughter by reading aloud to her on a stiff sofa, attired in a proper day dress with a bustle. The girl, in her tidy dress, apron and black stockings, has set aside her doll to listen, her dreamy face against her mother’s bosom showing the effect of the story on her imagination. In Reading a Story, Tissot depicts a similar scene in a natural setting, with a mother (Kathleen Newton) informally flipping pages on a comfortably-padded garden bench with a little girl who, though engaged, looks a bit fidgety as well as windblown from outdoor play.

Left: Alice in Wonderland (1879), by George Dunlop Leslie

Right: Reading a Story (c. 1878-79), by James Tissot

Tissot did not portray Victorian poverty, or even attempt to document the reality of the era’s social ills. In the images below, Philip Hermogenes Calderon (1833 – 1898) and George Adolphus Storey (1834 – 1919) depict destitute orphans in an attempt at realism colored with sentimentality. Tissot’s upper-class orphan, accompanied by the expensively-dressed woman modeled by Kathleen Newton, is somber, but sentimental in an essentially decorative way.

Above left: Orphans (1870), by Philip Hermogenes Calderon

Above right: L’Orpheline (1879), by James Tissot

Right: Orphans (1879), by George Adolphus Storey

The pictures below perfectly capture the difference between Tissot’s “modern” paintings and those of his Victorian peers.

Above left: Considering a Reply (c. 1860), by George Dunlop Leslie

Above right: The Letter (c. 1878), by James Tissot

Right: Reading the Letter (1885), by Thomas Benjamin Kennington

While Thomas Benjamin Kennington (1856 – 1916) depicts a woman reading a letter, and George Dunlop Leslie shows us a woman who has read a letter and now must consider how to reply, Tissot gives us a woman who, having read her letter, rips it to shreds that billow away in the wind. Kennington’s and Dunlop’s compositions are simple, but Tissot provides an air of tantalizing mystery around his subject: the woman stalks toward us through an elegant, landscaped garden while the remnants of her luncheon, or tea, are being cleared by a footman. Who is she? We are drawn into her drama, and are all the more curious about the contents of her letter.

James Tissot, unlike his Victorian peers, did not portray women gathering flowers or gazing at themselves in a mirror, or brides, or women sewing or dancing.

But for a cozy scene of a Victorian lady minding her children, he gave us Hide and Seek (left, c. 1877), in which Kathleen Newton lounges in an upholstered armchair, absorbed in a newspaper in a corner of his opulent studio while her children and those of her sister scamper about.

While Tissot used the brighter palette of the Impressionists in France, his perspective can be ascribed to his nationality only partially: his subject matter and his innate humor were unique.

© 2018 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related posts:

The Stars of Victorian Painting: Auction Prices

Victorians on the Move, by James Tissot

The James Tissot Tour of Victorian England

James Tissot and the Pre-Raphaelites

James Tissot’s Model and Muse, Kathleen Newton

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYV