To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot and the Pre-Raphaelites.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2018/06/18/james-tissot-and-the-pre-raphaelites/. <Date viewed.>

There is very little documentation on James Tissot’s personality, behavior, and habits, including his interaction with the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. We can only extrapolate their relationships based on a few known facts.

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation, 1849-50), by D. G. Rossetti (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

The leading members of the P.R.B., all ambitious art students in their early 20s, were William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), and John Everett Millais (1829–1896), and the rebellious aim of their secret society was to create a new British art. Rather than paint mannered historical or dull genre scenes, they wanted to return to the sincerity, minute detail, and luminous palette of medieval and early Renaissance painting. They began with an attempt to revive religious art but quickly resorted to literary subject matter.

The first P.R.B. works appeared at the Royal Academy Exhibition in 1849, when James Tissot (1836 – 1902) was 13 years old. In six years, he moved to Paris, and became an Academically-trained painter, favoring medieval subjects. He was greatly influenced by the work of the Belgian painter Hendrik Leys (1815 – 1869). Leys’ painting, The Trental Mass of Berthal de Haze – replete with numerous characters enacting a medieval drama against a minutely-detailed architectural background – won a gold medal at the 1855 Paris International Exhibition.

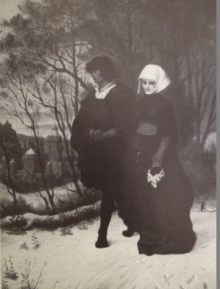

A Walk in the Snow, by James Tissot

In 1862, Tissot traveled to London, where the first exhibition of his work was not at the Royal Academy but the International Exhibition. Tissot showed one of his début paintings from the 1859 Salon, giving his medieval picture the English title, A Walk in the Snow.

He also must have met Britain’s most popular painter, John Everett Millais, who had moved to London with his wife, Effie. With their growing family to provide for, Millais found a steady source of income drawing illustrations, for periodicals such as Once a Week and The Cornhill Magazine as well as Tennyson’s Poems (1857) and Anthony Trollope’s novel Framley Parsonage (1860).

At the 1862 London International Exhibition, the retired first British Minister to Japan, Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897) showed his collection at his Japanese Pavilion. It was a sensation. With the signing of the first commercial treaty between Japan and America in 1854, more than 200 years of Japanese seclusion came to an end. In Paris, a host of import shops cropped up, and like Alcock, those with the means could collect exotic treasures – handcrafted pottery, lacquer, bamboo and ivory – that seemed even more exquisite compared to the Industrial Revolution’s mass-produced wares.

Young Women Looking at Japanese Articles (1869), by James Tissot. (Image Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library)

Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who lived in Chelsea near James McNeill Whistler, tried to shop for Japanese items in Paris in November, 1864. But, as he wrote to his mother from Paris, he “found all the costumes were being snapped up by a French artist, Tissot, who it seems is doing three Japanese pictures, which the mistress of the shop described to me as the three wonders of the world, evidently in her opinion quite throwing Whistler into the shade.”

Rossetti’s comment indicates that James Tissot was unknown to him prior to this, and that, with resentment at losing out on these treasures to him, he imagined Tissot was an inferior artist.

However, Rossetti became an admirer of Tissot’s work within months, when a book was published that included illustrations by several artists, including Millais and Tissot. On February 3, 1865, Rossetti wrote to his friend, Alexander Macmillan, “I have seen the frontispiece & vignette to Tom Taylor’s Breton Ballads [Ballads and Songs of Brittany] designed by Tissot, which are admirable things. Could you as their publisher let me have a proof of each separate from the work?” Macmillan made Rossetti a gift of one of Tissot’s drawings, either The Crusader’s Wife or the one for the frontispiece.

Apple Blossoms (Spring, 1859), J.E. Millais. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Spring (1865), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Tissot continued to be inspired by Millais. At the Paris Salon of 1865, though one of Tissot’s medieval pictures was a disappointment to the critics, his second picture, Spring, received some praise because of its similarities to Millais’ Apple Blossoms (Spring), exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1859.

Portrait of Effie Millais (1873), by J.E. Millais (Photo: Wiki)

In early June, 1871, Tissot fled Paris, along with thousands of others, after the Bloody Week, when French government troops brutally suppressed the Commune uprising that followed the Franco-Prussian War. He arrived in London with 100 francs in his pocket, but he had had enough time to pack a few drawings before he left Paris: on June 19, 1871, he dedicated an exquisite graphite rendering of a reclining French soldier at his ease with a rifle to Effie Millais (1828 – 1897). Tissot had fought bravely in the Battle of Malmaison, west of Paris, on October 21, 1870; this drawing is inscribed to Effie, “a la Malmaison/le 22 Oct 1870.”

With the help of a handful of friends, including Millais, Tissot proceeded to rebuild his career in London.

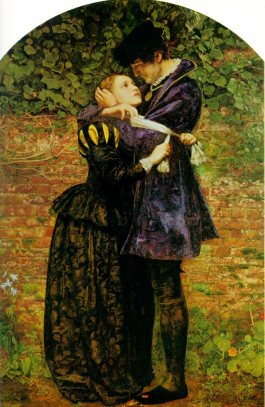

A Huguenot, on St Bartholomew’s Day, refusing to shield himself from danger by wearing the Roman Catholic badge (1851-52), by J.E. Millais. (Photo: Wiki)

Les Adieux (The Farewells, 1871), by James Tissot. (Photo courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library)

At the Royal Academy exhibition in 1872, Tissot showed Les Adieux (The Farewells, 1871). A sentimental costume piece calculated to appeal to the British public, it clearly was inspired by Millais’ A Huguenot (1851-52). Neither the critics nor the public objected to the French artist’s emulation of a Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece; rather, Tissot’s painting was so popular that it was reproduced as a steel engraving by John Ballin and published by Pilgeram and Lefèvre in 1873.

The Hammock (1879), by James Tissot. (Image courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library)

Later in the decade, when Tissot ceased exhibiting his work at the Royal Academy and instead displayed it at the innovative, elegant new Grosvenor Gallery, his supreme talent was acknowledged, but his paintings were considered a perversion of Pre-Raphaelitism:

“Mr. James Tissot, one of the eccentrics of the Grosvenor school, has sent in eight pictures. In six or seven of them the leading figure is a girl in a hammock or in a swing, or lying down. She is always surrounded by green trees and green grass, so green that you have to hunt for the figures, and so clever that you want to have Mr. Tissot sent for that you may call him names for prostituting his talents to a silly affectation of realism. Pre-Raphaelitism gone mad is the motive power of this wild man of the studio. Whistler has not quite satisfied us whether he can paint or not; but under Tissot’s eccentricities lurks a laughing giant.” The New York Times, May 12, 1879

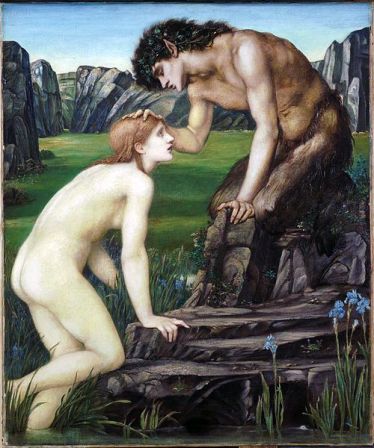

Pan and Psyche (1872-74), by Edward Burne-Jones. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

In an 1896 letter to Helen (May) Gaskell, Edward Burne-Jones (1833 – 1898), who had been a close follower of Rossetti, described Tissot’s paintings of “ladies in hammocks, showing legs & ladies smoking – and all manner of things not tending to edification.” Burne-Jones had met and fell in love with May, an unhappily married Society hostess, in 1892.

Burne-Jones’ wife of thirty-eight years, Georgiana (1840 – 1920), wrote to Tissot after her husband’s death, asking if they had ever met or if there had ever been any correspondence between the two artists. In January, 1899, she received a letter from him with a “beautiful answer” to her questions:

Georgiana Burne-Jones, c. 1882. (Photo: Wikimedia)

“I am back from America and upon my return I find your letter which I hasten to answer. I did not know your husband very well. I only remember that around 1875 I went to see him; he received me with great simplicity, and I judged the man according to what I saw in his studio – that is, great things on the easel rendered with a touching primitive simplicity. I felt the heights where he hovered and the materiality where I struggled more and more; all this intimidated me so much that I was not going to see him anymore. He grew so much and I left England. Since then I have made this Life of Christ, I know he has been to see it. I knew he liked it, and I would have a really good time seeing him on one of my trips to London when I learned of his death. He never wrote to me, otherwise I would put at your disposal what would remain of this great artist, one of the purest glories of your country. ”

Tissot, one of the most self-confident, ambitious and materially successful artists of his time, offered these effusive sentiments to a widow tasked with writing her husband’s biography.

The Finding of the Savior in the Temple (1854–60), by William Holman Hunt. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

As for the third leading founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, William Holman-Hunt wrote in his memoir, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Vol. II:

“The Franco-German war had brought many French artists to England, some of whom had returned to Paris, while others remained here. One evening at a small bachelors’ gathering at Millais’ studio, a foreigner, being told that I had just returned from Jerusalem, asked if I were Holman-Hunt, the painter of ‘The Finding of Christ in the Temple’ [1854-55], which he had lately seen in Mr. Charles Mathews’ collection. He said that he had admired it and my principle of work so much that he had resolved some day to go to the East and paint on the same system. I then learnt that this artist was young Tissot.”

The Youth of Jesus (1886-94), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Either this is true, and “young Tissot,” finding himself rebuilding his reputation in London at age 35, taking career cues from the practical, businesslike Millais, dreamed of imitating Holman-Hunt’s artistic quest in the Holy Land – or, more likely, Holman-Hunt as an elderly man was burnishing his reputation by taking credit for inspiring Tissot’s highly lucrative Bible illustrations, researched in Palestine after a “spiritual awakening” in 1885 and published to worldwide acclaim in 1896 and 1897. Tissot’s series of 365 gouache illustrations for the Life of Christ were shown to wildly enthusiastic crowds in Paris (1894 and 1895), London (1896) and New York (1898), after which they toured North America until 1900, bringing in $100,000 in entrance fees; the Brooklyn Museum then acquired them by public subscription for $60,000. After Tissot’s death in 1902, his assistants completed his Old Testament project, which was published in 1904. Holman-Hunt published his autobiography in 1905.

And so, from James Tissot’s earliest years as a painter until his death, the Pre-Raphaelites were intertwined with him and his success.

© 2018 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related Posts:

London Début: Tissot explores a new art market, 1862

Ready and waiting: Tissot’s entrée, 1865

The competition: Tissot’s friends Whistler, Degas, Manet, Courbet, Alma-Tadema & Millais in 1866

Welcome to the Royal Academy Exhibition: London, 1870 (Part I)

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9).

See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.