To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot and the Revival of Victorian Art in the 1960s.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2014/07/31/james-tissot-and-the-revival-of-victorian-art-in-the-1960s/. <Date viewed.>

All auction prices listed are for general reader interest only, and are shown in this order: $ (USD)/£ (GBP). All prices listed are Hammer Price (the winning bid amount) unless noted as Premium, indicating that the figure quoted includes the Buyer’s Premium of an additional percentage charged by the auction house, as well as taxes.

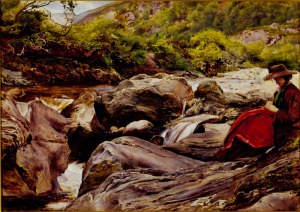

The Waterfall, by J. E. Millais (1853). This picture at the Delaware Museum of Art shows John Ruskin’s wife, Effie, in Scotland the year before their marriage was annulled.

Victorian art wasn’t dead by the 1960s, just buried. It was accessible in the Pre-Raphaelite collections of Birmingham and Manchester, the collection at the Lady Lever Art Gallery at Port Sunlight, and specialized collections such as the Watts Gallery, Leighton House and the William Morris Gallery, among other galleries in the United Kingdom.

In the U.S., the Delaware Museum of Art boasted a collection of British nineteenth-century art bequeathed by the descendants of Wilmington textile mill owner Samuel Bancroft, Jr. (1840 – 1915) in 1935. Bancroft and his wife, Mary, had acquired the collection from 1880 to 1915, advised by the Pre-Raphaelite painter, collector and art dealer Charles Fairfax Murray (1849 – 1919).

The Blessed Damozel (1871-78), by D.G. Rossetti, Fogg Museum. Winthrop paid £ 630 for this painting in 1934.

American lawyer and banker Grenville L. Winthrop (1864 – 1943) collected French, British, and American art, including a significant group of Pre-Raphaelite paintings. Upon his death in 1943, Winthrop left his entire collection of more than 4,000 works of art, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel (1871-78) and Edward Burne-Jones’ Pan and Psyche (1872-1874) to the Fogg Museum at his alma mater, Harvard College.

But at London’s Tate Gallery, the Pre-Raphaelites were displayed in a small basement room next to the public lavatories.

Nevertheless, Victorian art was savored behind closed doors, by a few connoisseurs delighting in the imagery of a by-gone era. Generally, it was scorned by sophisticates from art historians to collectors as mawkish, old-fashioned rubbish. Collecting it was a cheap enough hobby for those with some spare cash.

British artist L.S. Lowry (1887 – 1976) began to collect paintings and drawings by Rossetti after his own work, featuring industrial landscapes with factory workers, started selling for large sums in the 1950s. Lowry was president of the Rossetti Society, a select group of Rossetti owners founded in 1966; the collection he left upon his death in 1976 is now at The Lowry in Salford Quays, in greater Manchester.

Music (1877), by Burne-Jones

Kerrison Preston (1884 – 1974), a Bournemouth solicitor, had formed an impressive collection of Victorian art in the 1930s. After his elderly daughter died at Oxford in 2006, Rossetti’s Hamlet and Ophelia (1866) was discovered in the kitchen of her small house, and Burne-Jones’ Music (1877) – which Preston had acquired after it sold at Christie’s in 1934 for £ 147 – was found in her sitting room. Both masterpieces, worth well over £ 1 million, entered the collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 2008.

But to the public of the 1960s, these were unknown private collections.

Seeing the work of James Tissot remained a rare pleasure. As of 1960, there were only fifty-three oil paintings by James Tissot in public art collections worldwide: nineteen in the U.K., two in the Republic of Ireland, eighteen in France, eight in the U.S., one in Canada, one in India, two in New Zealand, and two in Australia.

There was only one couple who collected Tissot oils, as part of their collection of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, drawings and sculptures: Wall Street magnate John Langeloth Loeb (1902 – 1996) and his wife, Frances “Peter” Lehman Loeb (1907 – 1996), former New York City Commissioner to the United Nations. Since the late 1950s, the Loebs had been forming what would become, over the next four decades, one of the greatest private collections of art in the United States. They displayed their paintings in their Park Avenue apartment, which they opened to curators as well as art historians and their students.

July (Speciman of a Portrait) (1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34 7/16 by 24 in. (87.5 by 61 cm). Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio. (Photo: Wikimedia.org). In this version, a frizzy red hairstyle has been painted on the model; in the version called “Seaside,” now in a private collection, the model wears a tight blonde bun.

In 1960, Sir J.K. [John Kenyon] Vaughan-Morgan (1905 – 1995), a conservative Member of Parliament from Reigate, Surrey, from 1950 to 1970, sold Tissot’s Seaside to John L. Loeb as Ramsgate Harbour through the London art dealer, Agnew and Sons.

Loeb’s collection of twenty-nine paintings already included two Tissot oils; he had acquired La Cheminée (By the Fireside, c. 1869) in 1955 and Dans la serre (In the Conservatory, 1867-69) in 1957.]

A version of Seaside called July (Speciman of a Portrait) is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

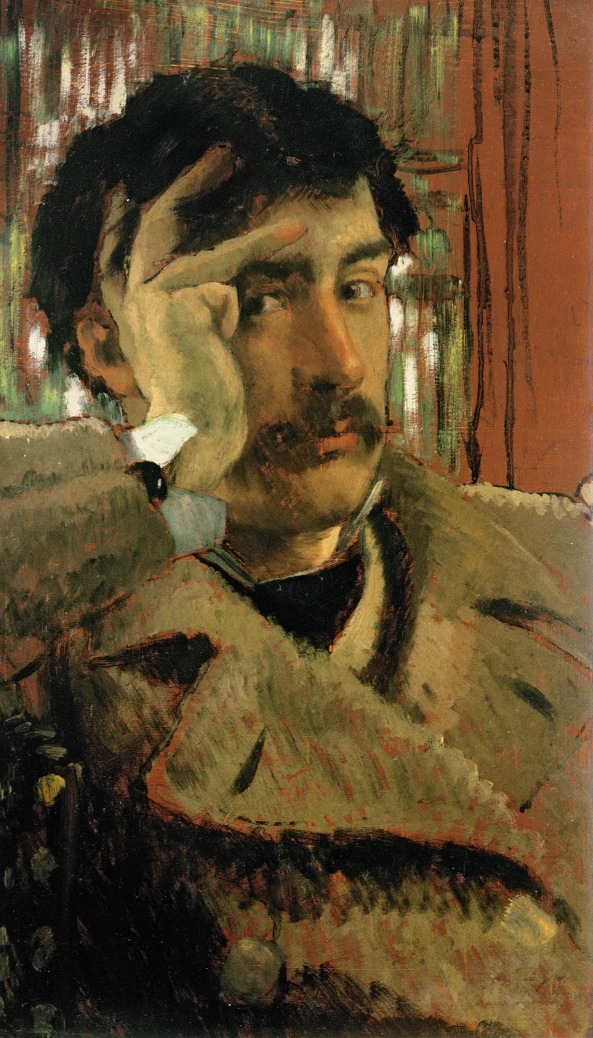

Self portrait (c. 1865), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 19 5/8 by 11 7/8 in. (49.8 x 30.2 cm). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA, USA. Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot” by Lucy Paquette, © 2012.

In 1961, Tissot’s Self-Portrait (c. 1865) was acquired by The California Palace of the Legion of Honour, San Francisco. This self-portrait shows him at 29, on the cusp of the spectacular success he would earn in Paris during the five years before the Franco-Prussian War broke out and he rebuilt his career in London. A hundred years later, his work was coming back into fashion – riding the breaking wave of interest in Victorian art.

The Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, one of several museums that went against art trends, purchased William Holman Hunt’s Lady of Shalott (c. 1890 – 1905). It was purchased at Christie’s, London in June, 1961 for $ 26,599/£ 9,500.

That year, Agnew’s, London held an exhibition, Victorian Painting 1837-1887, in cooperation with the newly-founded Victorian Society.

The Finding of Moses, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Then there was Alma-Tadema’s The Finding of Moses (1904). It was purchased upon completion by Sir John Aird (1833 – 1911), the engineer who moved the Crystal Palace from Hyde Park to Sydenham and oversaw the construction of the Aswan Dam in Egypt, for £ 5,250 (plus the artist’s expenses). Aird’s family sold the picture for £ 820 in 1935, and when it sold again in 1942, it fetched only £ 265. In 1960, the painting was offered for sale at the Newman Gallery in London, and it didn’t even meet the reserve, or the confidential minimum price agreed upon between the owner and the auction house (in this case, known to be £ 252), so it did not sell.

By 1963, Charles Jerdein (1916 – 1999), a London art dealer and former thoroughbred trainer, pioneered the market for paintings by Alma-Tadema, but he somehow missed The Finding of Moses.

The Newman Gallery offered Alma-Tadema’s painting to any public gallery that would take it as a gift, but no one wanted it. Newman then sold it to the owners of the Clock House Restaurant in Hertfordshire, England, who later sold it to a dealer who sold it to another dealer, Ira Spanierman in New York, for $8,500. Spanierman would have been familiar with Alma-Tadema’s work, if only from the Robert Isaacson Gallery’s show in New York in 1962, “An Exhibition to Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Death of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1836-1912.” Spanierman sold The Finding of Moses in August, 1967 to American television celebrity Allen Funt (1914 – 1999) for $25,000, and Funt was to buy nearly thirty more Alma-Tadema paintings from him.

The American Abstract Expressionism that dominated the art market in the 1950s would soon cede to new art movements. Godfrey Pilkington (1918 – 2007), director of London’s Piccadilly Gallery from 1953 to 2007, hated abstract art, preferring “something not totally unconnected with the old-fashioned concept of beauty.” He observed that buyers were “nervous of buying something that they actually like,” investing instead in “pictures they don’t like because they’ve been told they are good.” He later noted, “Art was becoming big business and, what is more, it was becoming publicity business.”

Pilkington was not the only art dealer in London who was not an aficionado of the contemporary art vogue, or who was more interested in Victorian art even though the market for Victorian art was almost nonexistent.

Charlotte and Robert Frank, refugees from Nazi Germany, set up as dealers in St. James’s, London, in the early 1940s, specializing in Victorian art. In 1947, Robert Frank [who was the uncle of diarist Anne Frank] bought John Martin’s The Last Judgment (1853), which had been cut into four strips to decorate a screen, and restored it. Upon her death in 1974, Charlotte left the work to the Tate in memory of her husband, along with another Martin work that Robert had purchased in 1947, The Plains of Heaven (1851-53); her bequest reunited a monumental triptych that included Martin’s The Great Day of his Wrath (1851-53), which the Tate had purchased in 1945. After Robert Frank passed away in 1953, Charlotte Frank, working from a tiny room in a basement in St. James’s Street, became renowned for her percipience. In 1964, she bought William Dyce’s Welsh Landscape with Two Women Knitting (1860) at Christie’s, London, and sold it to Sir David Montagu Douglas Scott (1887 – 1986), a career diplomat, a year later for £ 950. The Sir David and Lady Scott Collection of two hundred forty-two 19th and 20th century works, begun in 1914 and continually growing, adorned the walls of the Scott’s home, the Dower House at Boughton House, Northamptonshire. When it was auctioned at Sotheby’s in 2008, Dyce’s celebrated picture sold for $ 816,800/£ 541,250 (including buyer’s premium) to a foreign buyer. An export ban was put on it by the U.K. government, and in 2010, National Museum Wales secured it for £ 557,218 with a mix of grants, donations and gifts.

In December 1960, 32-year-old British art dealer Jeremy Maas (1928 – 1997) left Bonhams auction house and, with a capital of £ 2,000, opened his own gallery in Clifford Street, Mayfair, to specialize in Victorian paintings.

Just before Christmas in 1961, Maas held his first Pre-Raphaelite exhibition, The Pre-Raphaelites and Their Contemporaries, the first commercial showing of the Pre-Raphaelites in the 20th century. The show featured one hundred twenty-six drawings and thirteen paintings, some of which were purchased by major museums and galleries, including the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. Maas began to educate his customers about Victorian artists even as Andy Warhol’s iconic, silkscreened Campbell’s Soup Can paintings ushered in the Pop Art movement.

Flaming June (1895), by Frederic Leighton. (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

A few years later, in 1963, a teenager named Andrew Lloyd Webber spotted Frederic, Lord Leighton’s Flaming June (1895) – dirty and unframed – in a Fulham Road shop window. He had been interested in Victorian art since he was eight years old, but the price tag read £ 50. “I was 15. I didn’t have £ 50,” he later said, “I’ve been kicking myself ever since.” He asked his grandmother if he could borrow the money to buy it, but she replied, “I will not have Victorian junk in my flat.” Flaming June was offered for sale at auction but failed to sell for its reserve price [the equivalent of $140 USD]. Jeremy Maas bought it in 1963 for £ 1,000, a very high price at the time, from a man who had bought it from his barber for £ 60. Unable to sell the painting to a British institution or collector, Maas finally persuaded Luis Ferré to buy it for £ 2,000, for his new museum in Ponce, Puerto Rico.

In the Louvre/L’Esthetique (1883-1885), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 58 by 39 3/8 in. (144.4 by 100.0 cm). Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Luis A. Ferré (1904 – 2003), a Puerto Rican industrialist, politician, patron of the arts and philanthropist, had traveled to Europe in 1956 and acquired art including many Pre-Raphaelite works. Ferré would state in an interview published in Forbes magazine in 1993 that ”everyone thought I was crazy” to buy Pre-Raphaelite art in the 1950s. On January 3, 1959, with seventy-two works of art, Ferré opened an art museum in a small wooden house in his birthplace of Ponce which became the extraordinary Museo de Arte de Ponce (Ponce Museum of Art). The museum’s renowned collection of Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian art includes James Tissot’s In the Louvre/L’Esthetique (1883-1885), which was purchased at Sotheby’s, London in April, 1959 for $ 2,099/£ 750 and entered the Ponce’s collection in 1962. Ferré also purchased Burne-Jones’ 1898 masterpiece, The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon, at auction at Christie’s in 1963.

The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon (c. 1881–1898), by Edward Burne-Jones. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Tissot’s work entered several museums in the U.S. and Canada at this time.

In 1963, prominent collector Mrs. Blakemore Wheeler gifted Tissot’s Waiting for the ferry outside the Falcon Tavern (1874), which had sold for $ 4,339/£ 1,550 at Christie’s, London in 1954, to the Speed Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.

Waiting for the ferry outside the Falcon Inn (1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 26 by 37 in. (66.04 by 93.98 cm). The Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Gentleman in a Railway Carriage (1872) was purchased for the Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts by the Alexander and Caroline Murdock de Witt Fund in 1965.

The Letter (c. 1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 71.4 x 107.1 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

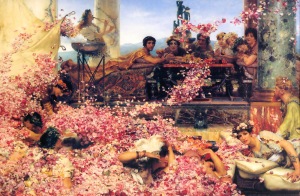

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, sold for $ 279 USD/£ 100 GBP at Christie’s, London in 1960 – and for $ 2,288,250 USD/£ 1,500,000 GBP at the same auction house in 1993. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

From 1953 until her death, The Letter (c. 1878) belonged to The Hon. Mrs. Nellie Ionides, née Samuel (1883 – 1962), eldest daughter of Shell Oil magnate Sir Marcus Samuel (later the 1st Viscount Bearsted), friend of Queen Mary, and a renowned London collector and connoisseur. It was sold with her estate in May 1963, by Sotheby’s, London to P. Claas (London) for $ 5,319/£ 1,900. In April, 1964, The Letter was purchased by New York art dealer James Coats, who immediately sold it to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario. [Coats, incidentally, was British and dealt privately out of his art-filled New York apartment, where Alma-Tadema’s decadent, seven-foot The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) hung over his bed. He lent a number of works to exhibitions at Robert Isaacson’s New York gallery, such as “Poetic Painters of the XIX Century” from December 1960 through January 1961, “Painters of the Beautiful” (Leighton, Albert Moore, Whistler, and Charles Conder) in 1964, and Simeon Solomon in 1966.]

In March, 1964, the new, and short-lived Gallery of Modern Art was opened in Manhattan by billionaire playboy Huntington Hartford (1911 – 2008), an heir to the A&P supermarket fortune.

Hartford, who loathed Abstract Expressionism, had just published Art or Anarchy? How the Extremists and Exploiters Have Reduced the Fine Arts to Chaos and Commercialism. In promoting the book, Doubleday noted that Hartford “challenges the artists, dealers, critics, and curators who have, in his view, blatantly duped the public for half a century.” He built the museum to house his extensive collection of 19th- and 20th-century representational art, which included paintings by Géricault, Courbet, Corot, Boudin, Degas, Monet, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Gustave Doré, J.M.W. Turner, Constable, Landseer, Millais, Burne‐Jones, Cassatt and John Singer Sargent. The gallery closed in 1969, at a $7.4 million loss, and the collection was dispersed.

In July, 1964, James Tissot’s niece, Jeanne Tissot (b. 1876), died, eccentric and impoverished. In November, the remaining contents of the Château de Buillon in Besançon, France, where they had lived together prior to his death in 1902, were auctioned off, the artist’s last mementos dispersed to various private collectors.

It was in 1964 that a successful Canadian couple, Joey and Toby Tanenbaum, began collecting Victorian paintings to decorate their new English-style home in Toronto. [Joey Tanenbaum (born 1932), the son of Polish immigrants who made their fortune in steel fabrication, is Chairman and CEO of Jay-M Enterprises Ltd. and Jay-M Holdings and has built his fortune through real estate and hydroelectric power.] But based on expert advice at that time, the Tanenbaums shifted their interest to “neglected” French artists of the same period. In February, 1968, they purchased James Tissot’s L’escalier (The Staircase, 1869) from art dealer James Coats in New York.

L’escalier/The Staircase (1869), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 22 by 15 in. (55.88 by 38.10 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Croquet (c. 1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 35.4 by 20 in. (89.8 by 50.8 cm). Art Gallery of Hamilton (Photo credit: Wikimedia.org)

Canadians seemed to have a special appreciation for Tissot’s work. In 1965, Croquet (c. 1878) was gifted to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, by Dr. and Mrs. Basil Bowman in memory of their daughter, Suzanne. Dr. Bowman (1902 – 1971), a dermatologist who practiced in Brockville, Hamilton, and Owen Sound, was a member of the board of management of the Art Gallery of Hamilton. The Convalescent (1872, also called A Girl in an Armchair) was a gift to the Art Gallery of Ontario from R.B.F. Barr, Esq., Q.C., in 1966. The Shop Girl (1883 – 1885) was a gift to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, from the Corporations’ Subscription Fund, in 1968.

British novelist Evelyn Waugh (1903 – 1966), became a collector of art and a connoisseur of Victorian pictures. Waugh, who was related by marriage to Pre-Raphaelite painters William Holman Hunt and Thomas Woolner, published his first book, Rossetti: His Life and Works, in 1928. Works he displayed in his home included Rossetti’s Woman Holding a Dog (c. 1860) and Spirit of the Rainbow (1876), a life-sized nude for which he paid £10 in 1938, and Holman Hunt’s Oriana. Upon Waugh’s death in 1966, his collection was dispersed.

London Visitors (c. 1874), by James Tissot. This painting, acquired by the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio from London art dealer Robert Frank in 1951, was exhibited in Ottawa in 1965 and in Rhode Island and Toronto in 1968. (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

Other museums began to act on the growing interest in Victorian art. There was an exhibition of the Pre-Raphaelites at the Herron Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1964, which then became the first loan exhibition at the Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art in New York. The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa held Paintings and Drawings by Victorian Artists in England in 1965, which became a loan exhibition at The Society of the Four Arts in Palm Beach, Florida in 1966. Numerous early Victorian and Pre-Raphaelite paintings were included in the exhibition, Romantic Art in Britain: Paintings and Drawings 1760-1860, in Detroit and Philadelphia in 1968, and that year, the Mappin Art Gallery in Sheffield held Victorian Painting. The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool held closely researched exhibitions of Ford Madox Brown in 1964 and William Holman Hunt in 1969. The first major John Everett Millais retrospective since 1898 was held in 1967 at the Walker and the Royal Academy. Paintings and Drawings from the Leathart Collection was held at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, in 1968; James Leathart (1820-1895) was a Newcastle lead manufacturer and a patron of artists who included James McNeill Whistler and the Pre-Raphaelites.

A Passing Storm (c. 1876), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart). This painting, exhibited in Rhode Island in 1968, is in the collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. It is now part of an exhibition called “Masterworks from the Beaverbrook Art Gallery.” It will be on view in Calgary, Alberta from May-August, 2014; in Manitoba from September-December, 2014; in Ottawa, Ontario in the summer of 2015; and in St. John’s, Newfoundland in the summer of 2016.

During February and March, 1968, the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence held James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836 – 1902): A Retrospective Exhibition, featuring thirty-nine of Tissot’s oils. The show traveled to the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto during April and May.

Also in 1968, petroleum geologist Robert Sumpf (1917 – 1994) gifted Tissot’s Promenade on the Ramparts (1864) to Stanford University in California, where he had earned his B.S. in geology in 1941.

Throughout the decade, other art dealers began to realize the potential in Victorian art.

Salthouse Dock, Liverpool (1892), by John Atkinson Grimshaw. A Northumberland couple bought this painting for £100 in 1960 and sold it for £185,000 in 2010. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

From the mid-1960s, Sir Robert Abdy, 5th Baronet (1896 – 1976) and Lady Jane Abdy (b. 1934) promoted the undervalued work of James Tissot and John Atkinson Grimshaw from the Ferrers Gallery, which they established at 9 Piccadilly Arcade, London after their marriage in 1962. Sir Robert inherited a large fortune which allowed him to live as a connoisseur and collector; he spent two years studying eighteenth-century furniture at the Louvre. (Since 1991, Lady Jane Abdy has been director of the Bury Street Gallery in South Kensington, London.)

Julian Hartnoll, one of the first dealers involved in the re-evaluation of Pre-Raphaelite art, established his art gallery in St. James in 1968, specializing in Victorian and Modern British Art. (Hartnoll is still at it, in his gallery at 37 Duke Street.)

Christopher Wood (1941 – 2009) joined Christie’s immediately on coming down from Cambridge in 1963. He started with six months on the front counter, picking up knowledge of art and prices from specialists, and a vacancy allowed him to work in the picture department, where he affixed photographs to cards and filed them. Wood was fascinated by Victorian artists, especially the Pre-Raphaelites, and he was convinced that “Victorian art was like a huge submerged continent waiting to be rediscovered.” By age 27, he was appointed a director in the European and British Nineteenth-Century Paintings Department. There were no separate Victorian sales until July 1968, with a sale that brought in a total of £ 74,000.

About this time, a casually dressed man about twenty years old, with dark hair down to his shoulders, introduced himself to Christopher Wood as Andrew Lloyd Webber. He was interested in the Pre-Raphaelites, and as he later said, “At that time it was deeply unfashionable to like them, which gave them added spice.” He had bought his first picture, a Rossetti drawing, a few years earlier for £ 12.

Ophelia (1894), by John William Waterhouse. (Photo: Wikimedia.org). In 1968, this painting sold at auction for $ 1,007 USD/£ 420 GBP; in 2000, it sold for $ 2,253,300 USD/£ 1,500,000 GBP.

Copiously illustrated books, including Graham Reynolds’ Victorian Painting (1966), Quentin Bell’s Victorian Artists (1967), and Jeremy Maas’ Victorian Painters (1969), fueled interest in the art of this long-ignored period.

In 1969, on spring break during his freshman year in college, Christopher (Kip) Forbes, of the American business magazine publishing dynasty, happened upon Graham Reynold’s Victorian Painting in a Bermuda bookshop. Just nineteen years old, Kip persuaded his father, Malcolm Forbes (1919 – 1990), “that for the price we had paid for a single late Monet [one in the Water Lilies series], we could have a collection of British Victorian paintings unrivaled in America outside a few museums.”

The collection of over 360 works of Victorian art that Kip Forbes and his father began in 1969 would include one well-known painting by James Tissot.

In 2003, The Forbes Collection of Victorian Pictures and Works of Art came up for auction and fetched £ 17 million. Later that year, London’s Royal Academy showed Pre-Raphaelite and Other Masters: the Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection, an exhibition featuring some 200 paintings by artists including Millais, Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Holman Hunt, Waterhouse Alma-Tadema and James Tissot.

© 2014 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Special thanks to

Helena Gómez de Córdoba

Exhibitions Coordinator and Curatorial Assistant, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico

Related posts:

James Tissot in the Roaring ‘20s

Tissot’s Comeback in the 1930s

James Tissot in the 1940s: La Mystérieuse is identified

James Tissot in the era of Abstract Expressionism

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.