To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot in the Roaring ‘20s.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2014/05/15/james-tissot-in-the-roaring-20s/. <Date viewed.>

At the time of James Tissot’s death in 1902, four of his oil paintings already had entered public art collections, and thirteen more were acquired in the following two decades. In the 1920s, twelve additional Tissot paintings entered museums around the world.

Portrait du Révérend Père Bichet (sometimes referred to as Portrait of a Priest, 1885), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34.25 by 46.06 in. (87 by 117 cm). Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, France.

In 1920, Albert Bichet bequeathed Tissot’s Portrait du Révérend Père Bichet (sometimes referred to as Portrait of a Priest, 1885) to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, France. Father Bichet was a missionary in Africa and the brother of Tissot’s sister-in-law, Claire Bichet (1844 – 1909).

Le Petit Nemrod (A Little Nimrod), c. 1882, by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34 ½ by 55 3/5 in. (110.5 by 141.3 cm). Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’archéologie, Besançon, France. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The same year, Albert Bichet made a bequest of Tissot’s Le Petit Nemrod (A Little Nimrod, c. 1882). It is in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’archéologie (Museum of Fine Arts and Archeology) in Besançon, France. The canvas depicts the children of Tissot’s mistress and muse, Kathleen Newton (1854 – 1882), and her older, married sister Mary Hervey, playing in a London park. Nimrod, according to the Book of Genesis, was a great-grandson of Noah, and he is depicted in the Hebrew Bible as a mighty hunter.

[Incidentally, Albert Bichet also owned Tissot’s The Two Sisters, which he gave to the Luxembourg Museum in 1904; it now is on view in Room 11 at the Musée d’Orsay.]

Sydney Isabella Milner-Gibson (c. 1872), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 51.18 by 37.01 in. (130 by 94 cm). (Bury St Edmunds Museum Service) (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

In 1921, antiquarian and author George Gery Milner Gibson Cullum of Hardwick House (now demolished), in Suffolk outside Bury St. Edmunds, died unmarried. The last surviving member of the Cullum baronetcy, he bequeathed most of the family portraits to the Borough of St. Edmundsbury, including a portrait of his older sister by James Tissot. The woman, Sydney Milner-Gibson (1850 – 80), also was the half-sister of Tissot’s British friend Tommy Bowles (Thomas Gibson Bowles, 1842 – 1922), and Tommy had commissioned Tissot to paint the portrait in 1872, when Sydney was in her early twenties. She died at Hardwick House, unmarried, of enteric fever* – typhoid, two days before her thirty-first birthday. Her portrait, which was valued at £1.8 million in 2012, is on display at Moyse’s Hall Museum in Bury St Edmunds, in the Edwardson Room first floor gallery as part of an exhibit on Victorian costume.

Note:* Previously, scholars reported that Sydney Milner-Gibson died of tuberculosis. However, a copy of Sydney’s death certificate was sent to me by reader Adam Mead of Bristol, U.K. Adam blogs on the Milner-Gibson family at https://milnergibson.wordpress.com/2013/08/03/the-milner-gibsons/. Thank you, Adam!

Still on Top (c. 1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34.65 by 20.87 in. (88 by 53 cm). Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Also in 1921, but on the other side of the globe, British industrialist and politician Viscount Leverhulme (1851 – 1925) gifted Tissot’s Still on Top (c. 1874), to the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in New Zealand, when it was worth approximately £ 500. In 1998, it was worth $3.5 million USD; click here to learn about the robbery of the painting that year, and the remarkable story of its recovery and restoration. Still on Top remains on display for Gallery visitors.

Waiting for the Train (Willesden Junction) (c. 1871-73) was purchased in 1921, with £89 5s from the Thomas Brown Fund, for the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand.

Willesden Junction is in northwest London, and was brand-new when Tissot painted it. The West Coast Main Line station was opened at Willesden Junction by the London & North Western Railway in 1866, with trains traveling to Birmingham and Scotland. The upper level station on the North London Line was opened in 1869 by the North London Railway, which ran trains east-west across Northern London. The modern woman portrayed in this ultra-modern setting looks at us with a direct, confidence gaze amid her baggage. Measuring just 23.46 by 13.58 in. (59.6 by 34.5 cm), it’s a small but fascinating painting.

Tissot’s Vive la République! (Un souper sous le Directoire), c. 1870, is possibly a sly reference to the new republican government declared in France on September 4, 1870, after Napoléon III’s surrender to the Prussians. This celebratory scene made its way to India, where it is now in the collection of the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery in Vadodara, Gujarat.

The museum – which resembles London’s Victoria and Albert Museum – was founded in 1887 by the Maharaja of what was then Baroda State (Sayajirao Gaekwad III, 1863 – 1939), for the education of his subjects. Construction of the picture gallery, a separate building, began in 1908, but it was opened in 1921 because of delays bringing art from Europe during World War I.

La Japonaise au bain (The Bather, 1864), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 81.89 by 48.82 in. (208 by 124 cm). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, France. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

La Japonaise au bain (The Bather, 1864) entered the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon, France in 1923 through a bequest by Dijon-born collector Gaston Joliet (1842-1921). Joliet was prefect [chief administrator] of Ain in 1890, then prefect of Poitiers in 1904 and governor of Mayotte, an archipelago off the coast of southeast Africa, between 1905 and 1906. He served as curator at the Dijon Musée des Beaux-Arts from 1916 to his death in 1921. La Japonaise au bain is on display.

The Warrior’s Daughter (A Convalescent), c. 1878, by James Tissot. Oil on panel; 14 ¼ by 8 11/16 in. (36.2 by 21.8 cm). Manchester Art Gallery, U.K. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org).

In 1879, the asking price for The Warrior’s Daughter (A Convalescent), c. 1878, at the Dudley Gallery, London was £ 125. The Manchester Art Gallery purchased it from the Leicester Galleries, London, in 1925. It is not on display. This is the fourth image of Kathleen Newton to enter a public collection, but her existence and name would remain unknown for another two decades.

Sur La Tamise (Return from Henley), c. 1874, by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 57.48 by 40.04 in. (146.00 by 101.70 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Sur La Tamise (Return from Henley), c. 1874, was sold as On the Thames by one private American collector to another, in 1916. It was acquired by physician, art collector and philanthropist Dr. J. Ackerman Coles (1843 –1925), of Scotch Plains, New Jersey and was donated to The Newark Museum, in Newark, New Jersey in 1926, the year after his death. Dr. Coles was a direct descendant of James Cole, a Puritan who arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, between 1620 and 1630, and his collection forms the cornerstone of the Newark Museum’s renowned holdings of nineteenth-century American art. However, The Newark Museum deaccessioned Tissot’s painting in 1985, when it was sold at Sotheby’s, New York, to a private collector for $ 370,000 USD/£ 293,860 GBP (Hammer price). In 2011, it was estimated to sell for $ 1,500,000 – 2,500,000 USD at Sotheby’s, New York, but it did not find a buyer.

A Portrait (1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 36 by 20 in. (91.4 by 50.8 cm). Tate Britain. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

A Portrait (1876), was exhibited by Tissot at the new Grosvenor Gallery, London, from May to June 1877. It was owned by John Polson, Thornley and Tranent, whose executors sold it at Christie’s, London, in 1911, as An Afternoon Call. It was purchased by the Dutch art dealer Elbert Jan van Wisselingh (1848 – 1912), London, for £44.2.0, and in 1927, the Tate purchased it from Mrs. Isa van Wisselingh (1858-1931) with the Clarke Fund. [Mrs. van Wisselingh, née Isabella Murray Mowat Angus, was the daughter of Scottish art dealer William Craibe Angus (1830 – 1899).] A Portrait is not on display.

Octobre (October, 1877), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 85 by 42.8 in. (216 by 108.7 cm). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

October (1877) was given to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal in Québec in 1927 by Scottish-born Canadian philanthropist Lord Strathcona (1820-1914) and his family, and it remains on display. I have seen this monumental painting – over 7 feet tall and 3 ½ feet wide – and it is much more charming and intimate than its size suggests. Though it was not known at the time, the canvas depicts Kathleen Newton, at age 23.

Holyday (c. 1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 30 by 39 1/8 in. (76.5 by 99.5 cm). Tate Britain. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Oscar Wilde, then a 23-year-old student at Magdalen College, Oxford famously skewered the subject matter of Holyday (c. 1876) as “Mr. Tissot’s over-dressed, common-looking people, and ugly, painfully accurate representation of modern soda water bottles.” In 1928, the painting was purchased by the Tate from Thos. McLean Ltd., a London art gallery, with the Clarke Fund. Holyday is on display at Tate Britain in room 1840; click here for an interactive look at it.

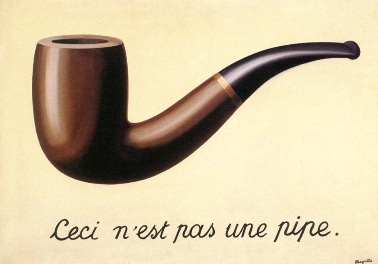

The Treachery of Images (1928-29), by René Magritte. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Just think how outmoded James Tissot’s images looked amid art movements during the 1920s, such as Surrealism and Art Deco.

And how disconnected his women were from the flappers of the Jazz Age!

But the bequests, donations and museum purchases of his paintings are a testament to their enduring beauty and an indication of their cultural value.

Josephine Baker in Banana Skirt from the Folies Bergère production “Un Vent de Folie” (1927). (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Related blog posts:

From Princess to Plutocrat: Tissot’s Patrons

Artistic intimates: Tissot’s patrons among his friends & colleagues

James Tissot Goes to the Museum

© 2014 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

Thanks for this post.

It would seem that the black-stripe-on-white dress seen in ‘Still on Top’ (1874) was a favorite–I’ve seen it (or something much like it) in two other Tissot paintings. He followed ladies’ fashions carefully. How well Tissot renders women’s fitted dresses–print, lace, frills, bustles and all!

So glad you enjoyed it! Tissot’s images of modern life were gorgeous, and it’s just as a critic wrote in 1869, “Our industrial and artistic creations can perish, our morals and our fashions can fall into obscurity, but a picture by M. Tissot will be enough for archaeologists of the future to reconstitute our epoch.” A century and a half later, those dresses look real enough to feel, as if you yourself are clothed in the silk and ruffles. He was unique, that’s for certain. Great to hear from you!