To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot and Alfred Stevens.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2015/09/15/james-tissot-and-alfred-stevens/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot’s work often is compared to that of Belgian painter Alfred Stevens (1823 –1906).

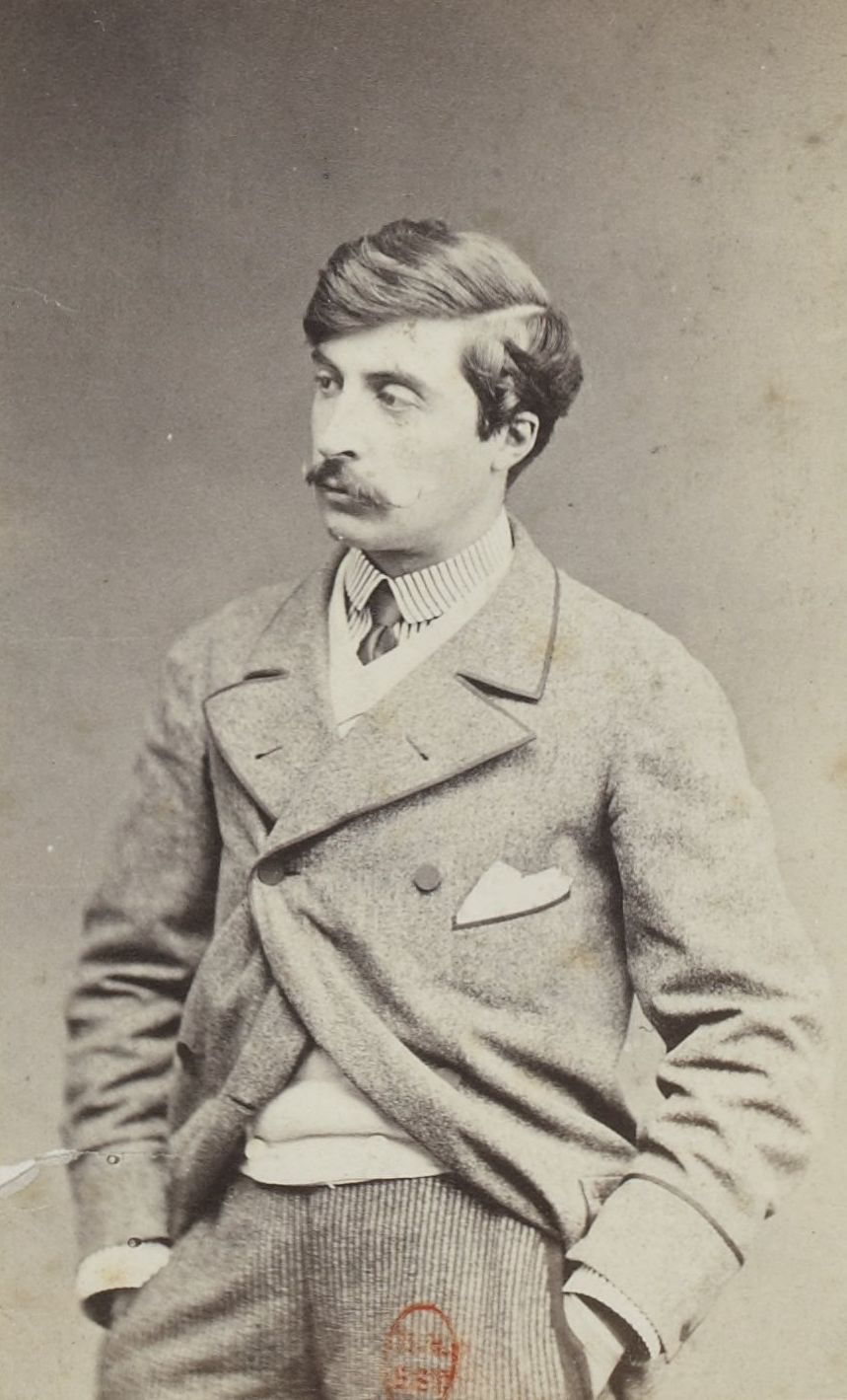

Alfred Stevens, 1865. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Stevens was born in Brussels, where he received his first artistic training. His father was an art collector, and his maternal grandparents ran a café that was a gathering spot for politicians, writers, and artists. Stevens’ elder brother, Joseph, was a painter, and his younger brother, Arthur, became an art critic and a dealer based in Paris and Brussels who advised the King of the Belgians.

Stevens’ father died in 1837, when he was fourteen, and in 1844, he went to Paris. He stayed with a friend, the painter Florent Joseph Marie Willems (1823–1905) and attended the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He studied under Camille Roqueplan (1802/03 – 1855), a friend of his father.

Stevens first exhibited his work in 1851, with four historical paintings at the Salon in Brussels. The next year, he settled in Paris. In 1853, at 30, he made his debut at the Salon there with three paintings; he won a third-class medal for Ash-Wednesday Morning, which was purchased by the Ministry of Fine Arts for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseilles. A year later, he also exhibited his first painting of modern life, The Painter and his Model [see below], at the Salon in Antwerp. In 1855, Stevens exhibited six paintings at the Exposition Universelle in Paris and won a second-class medal. Within a few years, he and his elder brother, Joseph, had become widely known and accepted in the Paris art world.

Lady at a Window, Feeding Birds (c. 1859), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

James Tissot, c. 1855-62. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Jacques Joseph Tissot’s parents were self-made, prosperous merchants and traders in the textile and fashion industry in Nantes, a bustling seaport on the banks of the Loire River, 35 miles from the Atlantic Ocean. Tissot left Nantes at 19, in 1856 (i.e. before he turned 20 that October).

In the spring of 1857, he enrolled at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, though there is little documentation on the regularity of his attendance at classes, which included mathematics, anatomy and drawing, but not painting. Tissot studied painting independently under Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1809 – 1864) and Louis Lamothe (1822 – 1869); both men had been students of the great Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780 – 1867), and taught his principles.

In 1858, Stevens married Marie Blanc, who came from a wealthy Belgian family who were old friends of the Stevens family. Eugène Delacroix, whose paintings were among those that Stevens’ father collected, was one of the witnesses at the ceremony.

Within three years of his arrival in Paris, Tissot was ready to exhibit his work at the Salon. Competing with established artists, the 23-year-old Jacques Joseph Tissot – likely borrowing the name from a new friend, the American artist James McNeill Whistler – submitted his paintings to the jury under the name James Tissot. Two of Whistler’s prints were accepted by the jury for exhibition in the Salon of 1859, but his strikingly original oil painting, At the Piano, was rejected, while five of Tissot’s entries were accepted, one called Portrait de Mme T…, a small painting of his mother. There was another small portrait (Mlle H. de S…), and two designs for stained glass windows. The fifth painting was Promenade dans la Neige, which depicted a young medieval couple taking a winter’s walk and caused one critic to wonder if Tissot was amusing himself by placing student work in a frame. Of the medieval subject matter, the critic sniped at the young artist, “What are you, blind to the life around you?”

Faust and Marguerite (a study for The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 6.10 by 8.66 in. (15.50 by 22.00 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

However, Tissot and his painting, Le Recontre de Faust et de Marguerite (The Meeting of Faust and Marguerite) attracted the attention of the Comte de Nieuwerkerke, Director-General of Museums, who purchased the painting by an order of July 17, 1860 on behalf of the government for the Luxembourg Museum for 5,000 francs. This was a huge honor for the very young artist, who exhibited the painting at the Salon in 1861.

In the 1860s, Stevens became immensely wealthy due his paintings of stylish and refined contemporary parisiennes, characteristically in luxurious private residences, but occasionally in religious settings.

Le bouquet (c. 1861), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

In Memoriam (c. 1861), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: http://www.the-athenaeum.org)

Les rameaux (Palm Sunday, c. 1862), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Stevens exhibited Les rameaux (Palm Sunday, c. 1862), at the Paris Salon in 1863 (and again at the Exposition Universelle, the world’s fair, in Paris in 1867).

In 1863, when he was forty, Stevens received the Legion of Honor (Chevalier) from the Belgian government.

Princess Mathilde Bonaparte’s salon at 24 rue de Courcelles, Paris (1859), by Giraud Sébastien Charles (1819-1892). Musée national du château de Compiègne. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Among the places where Alfred Stevens and his brother, Joseph, socialized were the crowded literary and artistic receptions held weekly by Napoléon III’s cousin, Princess Mathilde. There, he may have met the young James Tissot; another of Tissot’s new friends, the writer Alphonse Daudet, (1840 – 1897), attended these soirées as well.

Tissot made a name for himself at the Salon in 1864, exhibiting portraits from modern life that were highly praised: The Two Sisters may have been a double portrait; the elder model reappears in Portrait of Mademoiselle L.L.

The Two Sisters (1863), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Portrait of Mademoiselle L.L. (1864), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Tissot’s work first showed the influence of Alfred Stevens at the Salon of 1866, with Le Confessional, which was described by a critic as “perhaps a little too much in the style of Alfred Stevens.”

Leaving the Confessional (1865), by James Tissot. (Photo: http://www.the-athenaeum.org)

Considering that Stevens began his career with a painting very much in the style of his friend, Florent Willems (compare the two paintings below), he must have enjoyed Tissot’s homage and certainly did not discourage it.

Painter at his easel shows his work to a girl (1852), by Florent Joseph Marie Willems (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The Painter and his Model (1855), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Tissot received a medal at the Salon of 1866 which made him hors concours, entitled to exhibit from now on without the jury’s scrutiny, and with this official recognition came financial success. Tissot now was 29 and Stevens was 43.

At the Salon in 1867, Tissot exhibited Jeune femme chantante à la orgue (Young Woman Singing to the Organ), depicting a fashionable woman singing a duet with a nun in a church’s organ loft and The Confidence. Both owe a debt to Alfred Stevens – although perhaps Stevens’ In the Country (c. 1867) [see below] owes something to Tissot’s The Two Sisters (1863).

The Confidence (1867), by James Tissot. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

In the Country (c. 1867), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

At the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867, Stevens exhibited eighteen paintings, including La dame en rose (Woman in Pink, 1866), and he won a first-class medal; he was promoted to Officer of the Legion of Honor and invited to an Imperial ball at the Tuileries Palace. Tissot exhibited Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née Thérèse Feuillant, a stunning portrait of the wife of one of his new, aristocratic patrons. The 30-year-old Marquise wears a pink velvet peignoir while leaning on the mantel in her sitting room at her husband’s château in Auvergne with a stylish Japanese screen behind her.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), by James Tissot. Digital image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Open Content Program.

.jpg)

La dame en rose (Woman in Pink, 1866), by Alfred Stevens. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Stevens’ La dame en rose, which depicts an elegantly gowned woman near a Japanese carved and painted table, admiring a doll from “her” collection, is often said to have inspired Tissot’s japonisme phase, along with Whistler’s paintings such as The Golden Screen (1864), The Lange Leizen of the Six Marks (completed 1864; exhibited at the Royal Academy that same year), The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (completed 1863-64; exhibited at the Salon in 1865), and The Little White Girl (completed 1864; exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1865). But Tissot’s The Bather (c. 1864) pre-dates Stevens’ La dame en rose. [See “The three wonders of the world”: Tissot’s japonisme,1864-67.]

Tissot and Stevens moved in the same social circle, which included Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Frédéric Bazille, Berthe Morisot and James Whistler as well as Dutch painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema. But while Tissot is said to have preferred quiet evenings with his friends in his splendid new home on the chic avenue de l’Impératrice (now avenue Foch), Stevens often gathered with friends at the Café Guerbois. In addition, he and his wife held regular receptions at their home on Wednesdays; weekly soirées were held by Madame Manet (Edouard’s formidable mother) on Tuesdays, Madame Morisot (Berthe’s formidable mother) on Thursdays, and Princesse Mathilde on Fridays.

Tissot attended Stevens’ receptions, as he noted in early 1868 in a hurried message to Degas scribbled on the back of a used envelope when he found Degas away from his studio: “I shall be at Stevens’ house tonight.”

Both James Tissot and Alfred Stevens had grown wealthy depicting the elegance of Parisian life during France’s Second Empire. But their comfortable lives were about to change.

Related posts:

Was James Tissot a Plagiarist?

More “Plagiarists”: Tissot’s friends Manet, Degas, Whistler & Others

“The three wonders of the world”: Tissot’s japonisme,1864-67

Paris c. 1865: The Giddy Life of Second Empire France

In a class by himself: Tissot beyond the competition, 1866

Degas’ portrait: Tissot, the man-about-town, 1867

On top of the world: Tissot, Millais & Alma-Tadema in 1867

What became of James Tissot and Alfred Stevens?

© Copyright Lucy Paquette 2015. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.