To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “James Tissot’s Animals.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2019/01/15/james-tissots-animals/. <Date viewed.>

Did James Tissot paint animals because they appealed to Victorian sensibilities, because they were part of the life around him that he recorded so faithfully, or because they enhanced his subjects with symbolic meaning?

Numerous artists of Tissot’s time achieved great success as animaliers – animal painters – including Sir Edwin Henry Landseer RA (1802 – 1873), Rosa Bonheur (1822 – 1899), Briton Rivière RA (1840 – 1920), and Charles Burton Barber (1845–1894). Landseer, also a notable sculptor who created the lions at Trafalgar Square, was popular with the aristocracy as well as the middle class, whose homes often featured reproductions of his works, which often sentimentalized dogs. Bonheur, a French artist popular in England, was known for her realistic depiction of animals, especially cattle. Rivière focused on animal subjects from the mid-1860s, and he grew famous as his animal paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy often were engraved. Barber, famous for his sentimental paintings of children and their pets, especially dogs, received commissions from Queen Victoria to paint her grandchildren and dogs.

Around 1868, Tissot’s Un déjeuner (A Luncheon), set in the French Directoire period (1795 to 1799), featured a small, furry white lap dog with floppy ears – perhaps a flirtatious companion in this scene of seduction.

When the British invaded and looted the Chinese Imperial Palace in 1860 during the Second Opium War, they brought pug dogs back to England, where they were first exhibited in 1861.

When the British invaded and looted the Chinese Imperial Palace in 1860 during the Second Opium War, they brought pug dogs back to England, where they were first exhibited in 1861.

The ancient breed treasured by Chinese emperors was highly fashionable in Europe up through the eighteenth century; now Queen Victoria owned and bred pugs. The dogs became popular and often were depicted in paintings, greeting cards, and postcards of the time.

The Queen’s pugs were painted by Scottish artist Gourlay Steell RSA (1819 – 1894) around 1867.

Anglophilia was fashionable in France at the time, and Tissot, painting in Paris while well aware of trends in England, began to include pugs in a series of paintings set in the Directoire: Fig. a, La Cheminée (By the Fireside, c. 1869); Fig. b, Unaccepted (1869); Fig. c, Jeune femme en bateau (Young Woman in a Boat, 1870); Fig. d, La partie carrée (The Foursome, 1870); and Fig. e, Un souper sous le Directoire (c. 1870). [See James Tissot’s Directoire series, 1868-71.]

a  b

b  c

c

d  e

e

Since Tissot’s compositions featuring pugs were painted shortly after the breed was rediscovered, and since they became the only dog breed he featured in this series, it is likely he included them to boost sales as well as to add a lively detail.

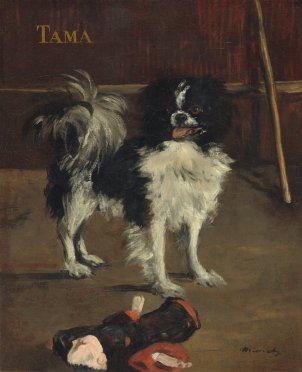

Tama the Japanese Dog (c. 1875), by Edouard Manet. (www.the-athenaeum.org)

Shortly after the fad for pugs began in England, the retired first British Minister to Japan, Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809 – 1897) made a sensation showing his collection of exotic treasures at his Japanese Pavilion at the 1862 London International Exhibition, beginning another trend that turned Tissot’s artistic (and business) inspiration away from pugs. After the signing of the first commercial treaty between Japan and America in 1854, more than 200 years of Japanese seclusion had come to an end. In the French capitol, a host of import shops cropped up to cater to the new craze for “japonisme,” and by November, 1864, when the famed Pre-Raphaelite artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti tried to buy Japanese items in Paris, he “found all the costumes were being snapped up by a French artist, Tissot, who it seems is doing three Japanese pictures.” These were three similar paintings featuring elegant young women looking at Japanese objects; French painter Berthe Morisot, after visiting the Paris Salon in 1869, wrote to her sister, “The Tissots seem to have become quite Chinese this year.” Tissot brilliantly used the chic “Oriental” studio in his new English-style villa in the rue de l’Impératrice (now avenue Foch) as a showcase to display his impressive collection of Japanese and Chinese art and artifacts, attracting princes and princesses – and commissions.

Focused on this new trend, Tissot ceased attracting buyers by adding the pug dog to his compositions, with the exception of Waiting (c. 1873, also known as In the Shallows), painted within two years of his emigration to England in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. A few years later, Tissot’s friend Edouard Manet combined the interest in dogs and japonisme in Tama the Japanese Dog (c. 1875), above, one of a few dog portraits he produced.

Waiting (In the Shallows, c. 1873), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wiki)

In a different vein, Tissot painted companion dogs in portraits of their aristocratic owners in France and England, and he rendered them with great skill and sensitivity.

Richard Peers Symons, MP (1770-71), by Joshua Reynolds (Photo: Wiki)

By 1865, Tissot had found an entrée to patrons in the French aristocracy and was commissioned to paint The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their children [René de Cassagne de Beaufort, Marquis de Miramon (1835-1882), his wife, née Thérèse Feuillant (1836-1912), and their first two children, Geneviève and Léon on the terrace of the château de Paulhac in Auvergne]. Tissot depicted them outdoors, as an informal, affectionate family in the English-style elegance of a Thomas Gainsborough (1727 – 1788) or a Joshua Reynolds portrait (1723 – 1792). In this painting, which served as Tissot’s calling card to the lucrative market for Society portraiture, he prominently features the Miramon’s large and regal black dog, a retriever or perhaps pointer mix that may have been the Marquis’ favorite hunting dog as well as a beloved family pet. An oil study for the painting shows that Tissot relocated the dog from what initially was conceived as a central position with Léon to a more natural pose at Léon’s feet; Tissot used the dog, in the end, to enliven the central spot at the bottom of the canvas. In a decision that finally unifies the subjects in a pleasing composition, Tissot changed the Marquis’ pose so that his crossed legs lead the eye down his long black boots to the strong black diagonal of the reclining dog. Tissot put as much thought into the dog’s placement in the painting as the human subjects, indicating its importance in the commission.

Three years later, in a group portrait of the members of The Circle of the Rue Royale (1868), Tissot featured a Dalmatian that clearly was important to at least one of the aristocrats who contributed toward the commission. Again, the dog is featured in the center of the composition, where its spotted coat enlivens the expanse of checkerboard marble tile and echos the colors of the stylish black and white hounds tooth trousers of Count Julien de Rochechouart, seated with a cigarette in his right hand. With its handsome profile and long body with outstretched paws, the Dalmatian has as much presence and poise as the twelve men in another composition emulating English-style portraiture of aristocrats and their dogs.

After emigrating to England with less than one hundred francs but with numerous British friends, Tissot received considerable help in establishing his career anew in London. Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821-1879), who shared Tissot’s interest in spiritualism, hosted fabulous salons in London and at Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. Frequent guests included Gladstone, Disraeli, and the Prince and Princess of Wales. In 1871 – shortly after Tissot had fled the Bloody Week in Paris – the charming and “irresistible” Countess Waldegrave pulled strings to get Tissot a lucrative commission to paint a full-length portrait of her fourth husband, Chichester Fortescue (right). It was funded by a group of eighty-one Irishmen including forty-nine MPs, five Roman Catholic bishops and twenty-seven peers to commemorate his term as Chief Secretary for Ireland under Gladstone – as a present to his wife. Fortescue, later Baron Carlingford (1823 – 1898) was a politically ambitious Irishman and Liberal MP for County Louth from 1847 to 1868. In 1863, he married the politically influential Countess Waldegrave, previously the wife of the 7th Earl Waldegrave, who had chosen him out of the three or more men who wished to marry her. Fortescue had been in love with her for a decade before her elderly third husband died. Tissot may have included the perky white terrier-type dog at his feet as a way of humanizing a quiet, bookish man described as “pedantic” but capable of great love.

After emigrating to England with less than one hundred francs but with numerous British friends, Tissot received considerable help in establishing his career anew in London. Frances, Countess Waldegrave (1821-1879), who shared Tissot’s interest in spiritualism, hosted fabulous salons in London and at Strawberry Hill in Twickenham. Frequent guests included Gladstone, Disraeli, and the Prince and Princess of Wales. In 1871 – shortly after Tissot had fled the Bloody Week in Paris – the charming and “irresistible” Countess Waldegrave pulled strings to get Tissot a lucrative commission to paint a full-length portrait of her fourth husband, Chichester Fortescue (right). It was funded by a group of eighty-one Irishmen including forty-nine MPs, five Roman Catholic bishops and twenty-seven peers to commemorate his term as Chief Secretary for Ireland under Gladstone – as a present to his wife. Fortescue, later Baron Carlingford (1823 – 1898) was a politically ambitious Irishman and Liberal MP for County Louth from 1847 to 1868. In 1863, he married the politically influential Countess Waldegrave, previously the wife of the 7th Earl Waldegrave, who had chosen him out of the three or more men who wished to marry her. Fortescue had been in love with her for a decade before her elderly third husband died. Tissot may have included the perky white terrier-type dog at his feet as a way of humanizing a quiet, bookish man described as “pedantic” but capable of great love.

Tissot also received a commission from his great friend, Tommy Bowles (Thomas Gibson Bowles, 1841 – 1922), who lived at Cleeve Lodge in Hyde Park. [To read more about their friendship, click here and here.] Tommy Bowles was the illegitimate son of Thomas Milner Gibson (1806 – 1884), a Liberal MP for Manchester and President of the Board of Trade from 1859 to 1866, and Susannah Bowles, a servant. Tommy was an adorable little boy, and his stepmother, Arethusa Susannah (1814 – 1885), a Society hostess who was the only child of Sir Thomas Gery Cullum (1777 –1855) of Hardwick House, Suffolk, insisted that he be raised with his father’s family of four sons and two daughters. Tommy’s favorite half-sister was Sydney Milner-Gibson, nearly eight years younger, and in 1871, when Sydney was 22, he commissioned Tissot to paint her portrait. Tissot captured the sweet, reticent personality and awkwardness of his friend’s beloved younger sister, who posed caressing her medium-sized black dog. The presence of her pet, which somewhat resembles a German Spitz, may have made her more comfortable, but it also fills the space created by the way she sits across the chair. Had she stood, with the dog at her feet, the composition would have been much less interesting.

f  g

g

The Victorians set great store by animals, and dogs especially exemplified loyalty and the affection and comfort of domestic life. In J.E Millais’ The Black Brunswicker (1860), left, the dog sweetly joins the woman in begging the soldier not to depart for battle.

The Victorians set great store by animals, and dogs especially exemplified loyalty and the affection and comfort of domestic life. In J.E Millais’ The Black Brunswicker (1860), left, the dog sweetly joins the woman in begging the soldier not to depart for battle.

The central figure in Briton Rivière’s Fidelity (1869), Fig. f, is impoverished, incarcerated, injured and abandoned by all – except for his dog.

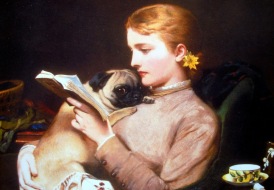

In Charles Burton Barber’s Blond and Brunette (1879), Fig. g, the affectionate pug and the pretty woman make an adorable duo.

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, innumerable such paintings were produced throughout the Western world playing to the emotional appeal of canine companions.

h  i

i

But James Tissot’s depictions of dogs had more in common with those of his friends in Paris than with those in sentimental Victorian paintings.

But James Tissot’s depictions of dogs had more in common with those of his friends in Paris than with those in sentimental Victorian paintings.

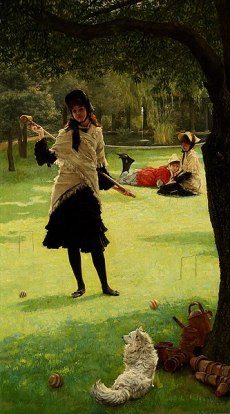

For instance, Tissot’s use of the white dog in Croquet (c. 1878), Fig. h, is more comparable to Edouard Manet’s inclusion of two small dogs in The Croquet Party (1871), Fig. i: the dogs simply are present, though they add motion and visual interest to the scene of human leisure activity.

The same is true of Tissot’s Fête Day in Brighton (c. 1875-78), right, in which the dog trotting ahead of the woman and the flags waving behind her add a sense of movement to her otherwise still figure, and a sense of depth to the picture.

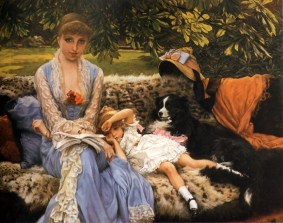

Tissot’s own border collie, which he painted in The Hammock (1879) (see below) and Quiet (c. 1881), Fig. j – reflect the artist’s realistic depiction of the scene. Akin to In Deep Thought (1881), Fig. k, by Alfred Stevens, Tissot’s friend in Paris, the dog mirrors the psychological state of the subject.

j  k

k

While dogs had symbolic meaning in art, James Tissot, a shrewd businessman, likely included dogs in many of his compositions because they appealed to Victorian sensibilities and because they were part of the life around him that he recorded so faithfully.

While dogs had symbolic meaning in art, James Tissot, a shrewd businessman, likely included dogs in many of his compositions because they appealed to Victorian sensibilities and because they were part of the life around him that he recorded so faithfully.

This is how Tissot painted other animals: not as fascinating creatures in their own right, as Edgar Degas painted racehorses, but in service to the people who were the subjects of his compositions: the horses in Les Adieux (The Farewells) 1871, and The Shop Girl (c. 1883-85) merely wait while their owners go about their business, and the horse in Going to Business (Going to the City, c. 1879), like the donkeys in The Morning Ride (1872-1876), and even (despite its title) the heron in On the Thames, A Heron (c. 1871-72), is providing the action in the scene without being its subject.

Tissot’s animals exist only in relation to the human psychology and activity that were the focus of his work.

© 2019 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related post:

Tissot’s Tiger Skin: A Prominent Prop

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYV