To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Was Cecil Newton James Tissot’s son?” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/10/20/was-cecil-newton-james-tissots-son/. <Date viewed.>

Was James Tissot the father of Kathleen Newton’s son, Cecil George Newton, born in 1876? It’s an interesting question, and to my knowledge, there is no documentation. It is widely speculated that Tissot was Cecil’s father. In the past four years that I’ve been researching Tissot, various online sources (art gallery biographies of Tissot, Wikipedia, art websites and blogs, etc.) once stated that Cecil “may have been” Tissot’s son, then that he “is believed” to be Tissot’s son or was “presumably his” – and increasingly, many now state that “it is generally accepted that Cecil is Tissot’s son” – but they cite no sources. To date, I have seen no evidence proving that this is a fact.

A Little Nimrod (1882), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

My research into a range of scholarly sources, and the facts on inheritance law in France during Tissot’s lifetime, lead to me conclude that Tissot was not Cecil’s father.

What is known is that Kathleen Irene Ashburnham Kelly married Dr. Isaac Newton on January 3, 1871, at age 17. Her daughter, Violet Newton*, was born on December 20, 1871, whether the daughter of her husband or the man – Captain Palliser – over whom her husband divorced her within days of their marriage (the decree nisi was issued on December 30, 1871). The focus of mystery is Kathleen’s second child, Cecil George Newton, born March 21, 1876; she registered his father as Dr. Isaac Newton.

Tissot went to Venice on holiday in early October, 1875 with Édouard and Suzanne Manet for several weeks. If he had fathered Cecil, it would have been by the end of June, leaving Kathleen Newton for Venice in the second trimester of her pregnancy; he returned by mid-November. The date that they began living together, supposed to be around 1876, coincides with this pregnancy and Cecil’s birth, but that in and of itself is not proof that Cecil’s father was James Tissot.

The first and only definitive assertion on the subject of Cecil Newton’s paternity is contained in a review (Art Journal, Vol. 45 No. 1, Spring 1985) of Michael Wentworth’s book, James Tissot, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984. The reviewer, Willard E. Misfeldt (a professor of Art History at Bowling Green State University, Ohio from 1967 to 2001), states, “As for Mrs. Newton’s second child, Cecil George, who was born in March 1876, more recent intelligence seems to settle positively the question of whether Tissot was his father.” The footnote cites “Family oral tradition communicated directly to this reviewer.”

Misfeldt writes, “This would mean that Tissot and Kathleen met no later than June 1875, and probably earlier.” He adds, “That Cecil and his sister occasionally visited Tissot in Paris [after the 1882 death of Kathleen Newton], as is stated, is probably accurate. The family preserves the story, however, that on one occasion when Tissot returned to London, Cecil refused to see him because he felt that he had been abandoned by his father.” This also is footnoted, “Family oral tradition communicated directly to this reviewer.”

Still, it is prudent to consider David S. Brooke’s assertion in his article, “James Tissot and the ‘Ravissante Irlandaise,’ ” (Connoisseur, May 1968). Regarding information provided by Kathleen Newton’s niece, Lilian Hervey (1875 – 1952), as an adult sharing her childhood memories, Brooke (who served as the director of the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts from 1977 to 1994) writes: “some of her observations on her aunt’s earlier life should be read with caution, since she was presumably given a suitable version of it by her elders.”

Brooke’s article also states: “Kathleen’s movements between December, 1871, and March, 1876, when she registered the birth of another child, Cecil George, giving Isaac Newton as the father, are not known [my italics]. In March, 1876, she was apparently living with her elder sister, Mary Hervey, at 6 Hill Road, St. John’s Wood, London, not far from Tissot’s house in Grove End Road. It is uncertain when Tissot met Kathleen Newton, or whether he was the father of Cecil George. She probably went to live with him about 1876-77.”

Study for “Mrs. Newton with a Child by a Pool” (c. 1877-78). Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

The article continues, “Tissot was clearly grief-stricken by Kathleen’s death [of tuberculosis on November 9, 1882], and according to Miss Hervey, he draped her coffin with purple velvet and prayed beside it for hours. Leaving for Paris a few days later, he apparently abandoned the house and its contents. According to a visitor at the time, his paints, brushes and several untouched canvases were still in the studio, and in the garden the old gardener was burning the mattress from the bed of the mysterious lady.” [Tissot left for Paris after the November 14 funeral. His elegant house at 17 Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood – now numbered 44, and renovated – sat empty until Lawrence Alma-Tadema purchased it in 1883.]

Brooke, at the end of this article, acknowledged the assistance of the following individuals: “Mrs. Erica Newton, for her research, and to Miss Marita Ross, for allowing me to reproduce the photographs of Tissot and Kathleen Newton. I am also indebted to Michael Wentworth, Willard Misfeldt (who is preparing a dissertation on Tissot), and Mrs. Erica Garbutt for their assistance.”

Willard Misfelt, in his 1971 doctoral dissertation on James Tissot, details the circumstances of Cecil Newton’s birth at 6 Hill Road, the home of Kathleen’s sister, Mrs. Mary Pauline Hervey (1851/52 – 1896). They lived just around the corner from Tissot’s large house at Grove End Road in St. John’s Wood, London. Mrs. Hervey (whose husband was said to be in the Indian army) had only lived at this address since “1876 or very late 1875,” according to Misfeldt: “If Tissot was the actual father of Mrs. Newton’s second child (she registered the father as the man who had divorced her five years earlier) the meeting would have taken place no later than June, 1875, and presumably earlier, at which time Mrs. Hervey and her entourage were nowhere near St. John’s Wood.” However, between the date of this dissertation and his 1985 review of Wentworth’s book on Tissot, Misfeldt learned of the “family oral tradition” that Cecil Newton was Kathleen’s son.

Other sources I consulted include:

- Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, ed., James Tissot (Barbican Art Gallery/Abbeville Press: New York, 1985)

Among the contributors to this collection of essays by Tissot experts is Lady Jane Abdy (b. 1934, the director of the Bury Street Gallery in South Kensington, London, since 1991). Lady Abdy writes, “A child was born in 1876, Cecil George, and we do not know whether it was Tissot’s, though in the tender way he depicted him in many portraits it seems probable.” She adds, “Mrs. Newton’s two children lived with Mrs. Hervey; they were visitors to Grove End Road, not inhabitants, and their visits usually occurred at the hour of tea.”

Hide and Seek (1877), by James Tissot. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot,” by Lucy Paquette © 2012.

- Christopher Wood, Tissot: The Life and Work of Jacques Joseph Tissot, 1836-1902 (Little, Brown: Boston, 1986)

In this work, Christopher Wood (1941 – 2009), director of Nineteenth Century Paintings at Christie’s, London from 1963 to 1976 and then an art dealer at the forefront of the revival in interest of Victorian art in the late 20th century with his gallery in Belgravia, stated that he did not believe Tissot was Cecil George Newton’s father. He pointed out that Tissot left his estate to his French niece, though under French law he could have adopted an illegitimate son and left him his property. Wood also argued that, like British painter Frederick Sandys (1829 – 1904) – who married a working class girl – Tissot could have married Kathleen and legitimized Cecil – if Cecil were his son. But then, it is possible that Kathleen Newton, as a divorced Catholic in that era, may not have felt able to remarry.

Uncle Fred (c. 1879-1880), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org) [A depiction of Kathleen Newton’s niece, Lilian Hervey, with a man thought to be Kathleen’s brother, Frederick.]

- Jeffrey Meyers, Impressionist Quartet: The Intimate Genius of Manet and Morisot, Degas and Cassatt (Harcourt, Inc.: Orlando, Florida, 2005)

Distinguished biographer Jeffrey Meyers put the issue of French law succinctly in this book, in a discussion of Édouard Manet and Léon Leenhoff – the young man raised by him and his wife as her “brother” and Manet’s godson:

“The Manet scholar Susan Locke noted that there was a good reason why Manet did not legitimize Léon: “in French law of the time, whereas nothing stood in the way of legitimization of children born out of wedlock upon the marriage of their parents, children born to individuals who were already married to others at the time of conception could never be legitimized under any circumstances.” In other words, Manet could have legitimized Léon if Léon were his own son. But he couldn’t, and didn’t, since Léon’s father was a married man.” [In Manet’s case, it is believed by some scholars that Manet’s father also was Léon’s father.]

By 1991, when Willard E. Misfeldt’s J.J. Tissot: Prints from the Gotlieb Collection was published (Art Services International, Alexandria, Virginia), Misfeldt wrote:

“Writers on Tissot have ‘fudged’ the question of Cecil’s paternity. Christopher Wood states outright that he does not believe Tissot was Cecil’s father. Georges Bastard [author of a 1906 biographical article on Tissot] asserts that Tissot and Kathleen shared a life of Love and Art for seven years, which would indicate that they met in 1875, some time before Cecil was born. It seems unlikely that Tissot would invite a woman pregnant with another man’s child to take part in his life. Perhaps the question can never be resolved, but the prominence that Tissot gave the child in these last two major paintings from London [The Garden Bench, 1882; The Little Nimrod, 1882] would seem to lend credence to the theory that Cecil really was the artist’s natural son.” A footnote reads, “Cecil kept up contact with Tissot and occasionally sent the artist souvenirs of his life in the theater.”

The Garden Bench (1882), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

I find it hard to believe that Tissot, in moving back to Paris upon Kathleen Newton’s death, would have abandoned his own son – his only son as well as his only child, and the child of the love of his life. Cecil [if legitimized] stood to inherit the family name with a château in Besançon, France in the family for two generations as well as an elegant villa at 64, avenue du Bois du Boulogne [originally called the avenue de l’Impératrice, now avenue Foch], one of the most exclusive addresses in Paris.

Based on my extensive research, James Tissot seems to have been a decent man who was kind to Kathleen’s daughter and son in the years the couple spent together. He painted Violet and Cecil as the adorable children they were – just as Millais, Renoir and other artists of the time painted numerous images of adorable children. In The Garden Bench, the mischievous boy (with his bold, direct gaze at the viewer) is highlighted, the center of his proud and indulgent mother’s attention, while the affectionate girls are relegated to the background, portrayed as demure and passive – all in keeping with the era’s assigned gender roles. Tissot kept The Garden Bench, hung in the central stair hall of his château for the rest of his life, as a reminder of his happy days of family life in London. There is no record of whether, or how often, Tissot exerted himself to keep in contact with Cecil Newton – but we do know what his Will, drawn up in January, 1898, provided upon his death in 1902.

While dividing his assets between the three surviving adult children of his eldest brother, James Tissot’s Will stipulated that each of Kathleen Newton’s two children (whose addresses were located by a servant) would receive 1,000 francs. Tissot’s servants were provided for more generously: each received 200 francs per year in his service, employment with full wages for a period of one year after his death, plus 1,000 francs.

Misfeldt reports this information in his 1971 doctoral thesis on Tissot, conjecturing that “equal sums for the two [children of Kathleen Newton] might have seemed the best way to avoid arousing any embarrassing suspicions concerning two children who were by then young adults.”

Cecil married at 28, two years after Tissot died, and served in the Royal Artillery during World War I under the name Cecil Ashburnham. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in 1915 and was discharged as an invalided officer less than a year later. He was divorced at age 48, and died as Cecil Ashburnham on May 4, 1941, at 21, First Avenue, Lancing (a town on the English Channel, near Brighton). Cecil left no Will, but his estate, valued for probate at £108.12s.6d, was administered by George Ashburnham Newton, of Llandudno, a seaside town in Wales.

With no conclusive evidence, I decided that it was as plausible that Cecil was not Tissot’s son as that he was, and I developed the story line for The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot accordingly as I continued my research.

As with any of the mysteries surrounding the fascinating life of James Tissot, I would be pleased to see facts emerge that prove one theory or another; I was trained as an art historian. As a novelist, I chose to portray the facts on this subject according to my best information at the time. To see how I reconciled the question of Cecil’s paternity, read The Hammock.

Kathleen Newton at the Piano (c. 1881), by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

* Muriel Violet Mary Newton, born on December 20, 1871 in Conisbrough (a town in South Yorkshire where Kathleen Newton’s father had retired from the East India Company), attended Pensionnat de Soeurs de la Providence et de l’Immaculée Conception at Champion-lez-Namur, Belgium. She married William Henry Bishop on October 19, 1925 in London and died of a heart attack on December 28, 1933 at the Hotel Cristina in Alcegiras, Spain. She is buried in Spain.

For biographical information on Kathleen, Isaac, Violet & Cecil Newton, see Willard E. Misfeldt’s J.J. Tissot: Prints from the Gotlieb Collection (Art Services International: Alexandria, Virginia, 1991).

© 2013 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

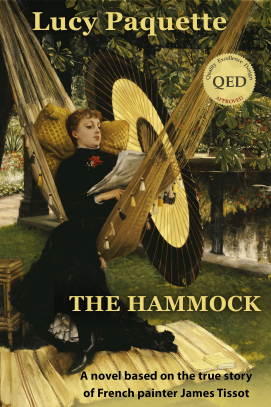

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.