To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. A spotlight on Tissot at the Met’s “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity”.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2013/05/06/a-spotlight-on-tissot-at-the-mets-impressionism-fashion-and-modernity/. <Date viewed.>

Last week, I visited “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The exhibition is overwhelmingly beautiful – almost too much to take in during one afternoon. The Manets, the Morisots – the gowns! It’s fabulous; you’re transported. See it if you can, and if you can’t – take the Met’s virtual tour, gallery by gallery. Among the wonderful exhibits is the actual costume worn in In the Conservatory (Madame Bartholomé). Albert Bartholomé (1848 – 1928) saved the two-piece summer gown after his wife, Périe (1849-1887), daughter of the Marquis de Fleury, passed away too young.

Besides not wanting to miss this show, I couldn’t miss the opportunity to view so many of Tissot’s oil paintings in a single venue. They are stunning.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, unframed: 50 1/2 by 30 3/8 in. (128.3 by 77.2 cm). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née, Thérèse Feuillant (1866), is on loan from The J. Paul Getty Museum, in Los Angeles, California, which acquired the picture from the family in 2007. Tissot depicts the 30-year-old Marquise in her husband’s castle, the château de Paulhac in Auvergne, leaning on the mantel in her sitting room with a stylish Japanese screen behind her. It’s gorgeous – the photograph doesn’t do it justice. The ruffles on her gown, which appear so precise, are lovely, curling brushstrokes. Alongside is displayed a sample of the pink silk velvet used in the Marquise’s peignoir, produced with a modern aniline dye. Her descendants kept this piece of fabric as well as the letter that Tissot wrote to her husband, who had commissioned the portrait, asking permission to display it at the 1867 Paris International Exhibition. Permission was granted, and this private image was seen by the public for the first time.

It’s unfortunately the fashion to criticize Tissot’s work harshly. A February 21, 2013 reviewer in The New York Times couldn’t resist disparaging the Portrait of Marquise de Miramon as “zealously detailed,” when that’s why it’s so wonderful. (Remember Scarlett O’Hara’s dressing gown in Gone with the Wind?) Visitors also are mesmerized by Tissot’s Portrait of the Marquis and Marchioness of Miramon and their children and The Circle of the Rue Royale. People (including me) vie for a position close enough to examine these pictures, clearly reluctant to step away. Tissot’s aristocratic images are magnetic, a bit voyeuristic, as they provide us with a glimpse of a lost world.

Two Sisters (1863), Portrait of Mademoiselle L. L. (1864), Portrait of the Marquis and Marchioness of Miramon and their children (1865) and The Circle of the Rue Royale (1868) all are from the Museé d’Orsay, Paris.

The Two Sisters (1863), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 82.7 by 53.5 in. (210 by 136 cm). Museé d’Orsay, Paris. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

The Two Sisters was sold from Tissot’s studio, a year after his death in 1902, to a collector in whose name it was given to the Luxembourg Museum, in Paris, in 1904. It has been in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay since 1982. This is the first time The Two Sisters has been shown in the U.S.

Portrait of Mlle. L.L. (Young Lady in a Red Jacket) (February 1864), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 48 13/16 by 39 3/8 in. (124 by 99.5 cm). Museé d’Orsay, Paris. (Photo: Wikipaintings)

Portrait of Mademoiselle L. L. was in the collection of the Luxembourg Museum from 1907 to 1929, when it was assigned to the Louvre; it has been at the Musée d’Orsay in 1978. I love this painting – a depiction of such an independent, intelligent, confident young woman – with its softly-rendered pompoms. Tissot’s paintings in the 1864 Salon – this one and Two Sisters – reflected the trend toward capturing “modernity,” and he began to hit his stride as an artist. Mademoiselle L.L. has been exhibited once in New York before, in 1994, as well as in New Haven, CT in 1999 and in San Francisco, CA and Nashville, TN in 2010.

The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children (1865), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 69 11/16 by 85 7/16 in. (177 by 217 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children is my very favorite Tissot painting. It’s gloriously lovely, a vision of perfection. I had to jostle through the crowd of admirers to thoroughly scrutinize every detail. The portrait remained in the family until 2006, when it was acquired by the Musée d’Orsay, and this is the first time it’s been exhibited anywhere else since 1866.

The Circle of the Rue Royale (1868), by James Tissot. 68 7/8 by 110 5/8 in. (175 by 281 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Circle of the Rue Royale fills a wall at the Met, and visitors manage to peel themselves away, only to backtrack and examine some other intriguing detail. Members of this exclusive club, founded in 1852, each paid Tissot a sitting fee of 1,000 francs. He portrayed them on a balcony of the Hôtel de Coislin overlooking the Place de la Concorde (if you look closely at the original painting, you can see the horse traffic through the balustrade). From left to right: Count Alfred de La Tour Maubourg (1834-1891), Marquis Alfred du Lau d’Allemans (1833-1919), Count Étienne de Ganay (1833-1903), Captain Coleraine Vansittart (1833-1886), Marquis René de Miramon (1835-1882), Count Julien de Rochechouart (1828-1897), Baron Rodolphe Hottinguer (1835-1920; he kept the painting according to the agreed-upon drawing of lots), Marquis Charles-Alexandre de Ganay (1803-1881), Baron Gaston de Saint-Maurice (1831-1905), Prince Edmond de Polignac (1834-1901), Marquis Gaston de Galliffet (1830-1909) and Charles Haas (1833-1902). The Musée d’Orsay acquired The Circle of the Rue Royale in 2011 from Baron Hottinguer’s descendants for about 4 million euros.

Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 19.5 by 23.5 in. (49.5 by 59.7 cm). National Portrait Gallery, London. (Photo: Wikipedia.org)

The small picture of Captain Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870) bursts with life. Burnaby is too, too debonair, and the flicks of paint that create the gleam on his shoes are fascinating. (I expected to be chastised for standing too close, but the guards were preoccupied with admonishing visitors that photographs are not allowed in the exhibition galleries.)

Tissot, 33 when he painted this image, owned a villa on the most prestigious avenue in Paris, and he occasionally supplied his British friend Tommy Bowles (Thomas Gibson Bowles,1841 – 1922), with caricatures of prominent men for Vanity Fair, Tommy’s new Society magazine which had made its début in London in 1868. One of Tommy Bowles’ closest friends was the dashing Gus Burnaby (Frederick Gustavus Burnaby, 1842 – 1885), a captain in the privileged Royal Horse Guards, the cavalry regiment that protected the monarch. Gus, a member of the Prince of Wales’ set, had suggested the name, Vanity Fair, lent Bowles half of the necessary £200 in start-up funding, and then volunteered to go to Spain to chronicle his adventures for the satirical magazine. All Burnaby’s letters, which were first published on December 19, 1868 and continued through 1869, were titled “Out of Bounds” and signed “Convalescent” (he suffered intermittent bouts of digestive ailments and depression throughout his life).

In 1870, Tommy Bowles, now 29, commissioned James Tissot to paint a small portrait of Burnaby. Tissot presented Gus in his “undress” uniform as a captain in the 3rd Household Cavalry – and as an elegant gentleman in a relaxed male conversation. The painting was purchased by London’s National Portrait Gallery from Bowles’ son (and Burnaby’s godson), George, in 1933. Burnaby’s posthumous travels over the years have taken him (among other places) to Providence, RI; New Haven, CT; Buffalo, NY; Washington, D.C. and San Francisco, CA. This exhibition takes him to Chicago next.

Ball on Shipboard (1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 33 1/8 by 51 in. (84.1 by 129.5 cm). Tate, London. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Ball on Shipboard (1874) and Portrait of Miss Lloyd (1876) are from the Tate Britain, London. Scholars have written that Tissot had a fixation with twins, but the Met’s show asserts that in Ball on Shipboard, Tissot was making a wry commentary on the rise of ready-to-wear fashion (and, of course, the tackiness of the nouveaux riches). This is not Tissot’s only painting of women wearing identical ensembles: see In the Conservatory (1875-76, also known as The Rivals). Part of the viewer’s fascination with Tissot’s paintings is the enigmatic quality of his images: they are as precise as photographs while they evade precise meaning. You find yourself transfixed as you try to puzzle it out.

Portrait of Miss Lloyd (1876), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 36 by 20 in. (91.4 by 50.8 cm). Tate, London. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Portrait of Miss Lloyd was purchased at Christie’s, London, in 1911 for £44.2.0 as An Afternoon Call and was acquired by the Tate in 1927. When Tissot painted it in 1876, he titled it A Portrait. The model for the drypoint version that Tissot made of this in 1876 was identified at a 1903 Paris auction as Miss Lloyd.

July (Speciman of a Portrait) (1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 34 7/16 by 24 in. (87.5 by 61 cm). Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

July (Speciman of a Portrait) (1878) is from the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio (bequest of Noah L. Butkin in 1980). One in a series representing months of the year, the figure is modeled by Tissot’s mistress, Kathleen Newton (1854 – 1882). Near this picture and Miss Lloyd’s portrait, the Met features a gown of the period very similar to Tissot’s prop costume, complete with graceful, loose bows of lemon-yellow satin ribbon. [Tissot also used this costume in A Convalescent and A Passing Storm, both painted in 1876, and Spring, c. 1878.]

Le Bal/Evening (1878), by James Tissot. 35 7/16 by 19 11/16 in. (90 by 50 cm). (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Kathleen Newton also modeled for Le Bal/Evening (c. 1885). The painting moved around Paris: it was at the Musée du Luxembourg from 1919 to 1920, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs until 1948, then at the National Museum of Modern Art until 1977, when it passed through the Louvre before being assigned that year to the Musée d’Orsay. Evening was exhibited in the U.S. in Atlanta, GA in 2002 and in Houston, TX in 2003.

After Kathleen Newton died in 1882, Tissot’s work lost something – heart, confidence, a compelling sense of himself present in his work from 1864 to 1882. In Paris, during and after the Franco-Prussian War, he already had lost so much – the carefree life he had as a young artist on the rise; his reputation as he, alone among his set, remained in Paris throughout the atrocities of the Commune, even his brand-new villa and studio as he fled to London and remained for a decade. He retained ownership of the villa and moved into a large home in St. John’s Wood. There, his paintings of his domestic life with Kathleen exude joie de vivre, but after he moved back to Paris, there’s something cold about his work.

Women of Paris: The Circus Lover (1885), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 58 by 40 1/4 in. (174 by 102 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The Circus Lover (1885) is one in a series of eighteen paintings called La Femme à Paris (Women of Paris). The setting for this picture is the Molier Circus in Paris, a “high-life circus” in which the amateur performers were members of the aristocracy. The man on the trapeze wearing red is the Duc de la Rochefoucauld, one of the oldest titles of the French nobility. The painting was purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts in 1958 for $5,000 as Amateur Circus. To closely examine its details, click here.

The Shop Girl (1883-1885), by James Tissot. 57.5 by 40 in. (146.1 by 101.6 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The Shop Girl (1883-1885), also part of the La Femme à Paris series, was acquired by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada, in 1968.

James Tissot’s work was – and is – denigrated by the critics, as being too good – too smooth, too detailed, too meticulous. The accepted line is that he didn’t bring enough that was innovative. Tissot was as technically proficient as the popular Alfred Stevens (1823 – 1906), in depicting female beauty and luxurious fashions. What Tissot brought was an eye for revealing character through detail, and his own urbane, wry wit.

Who but James Tissot could have portrayed the larger-than-life Gus Burnaby? Who but Tissot would depict the matron looking down her nose at the attractive young woman on the arm of a much older man in Evening? And who else would have painted the head of the man outside the display window over the neck of the window mannequin in The Shop Girl?

In 1869, the journal L’Artiste, in a review of Tissot’s painting, Young Ladies Looking at Japanese Objects, exhibited at the Paris Salon, commented, “Our industrial and artistic creations can perish, our morals and our fashions can fall into obscurity, but a picture by M. Tissot will be enough for archaeologists of the future to reconstitute our epoch.”

Tissot’s most arresting images have stood the test of time.

It was great fun to hop a train (with my all-too-willing husband) to spend an afternoon at the Met – and to view twelve Tissots at once.

Really, if you can’t make it there before the show closes on May 27, pour yourself a cold glass of champagne and Grand Marnier, have some chocolate-dipped strawberries on hand, and enjoy the virtual exhibition.

© 2013 Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

View my video, “The Strange Career of James Tissot” (Length: 2:33 minutes).

Exhibition Notes:

“Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” February 26 – May 27, 2013 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A revealing look at the role of fashion in the works of the Impressionists and their contemporaries. Some eighty major figure paintings, seen in concert with period costumes, accessories, fashion plates, photographs, and popular prints, will highlight the vital relationship between fashion and art during the pivotal years, from the mid-1860s to the mid-1880s, when Paris emerged as the style capital of the world.

For more information, visit

http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2013/impressionism-fashion-modernity

“Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” is coming to the Art Institute of Chicago Wednesday, June 26 – Sunday, September 29, 2013

http://www.artic.edu/exhibition/impressionism-fashion-and-modernity

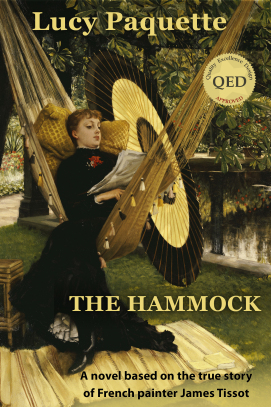

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

NOTE: If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

A superb post! Thanks so much for sharing your reflections – and these sumptuous images.

Russell, thanks! And I should have mentioned that “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity” is coming to the Art Institute of Chicago, Wednesday, June 26, 2013 through Sunday, September 22, 2013.

The word “sumptuous” describes the exhibition – and Tissot’s works – perfectly!