To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Tissot’s Study for the family of the Marquis de Miramon (1865).” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2016/12/14/tissots-study-for-the-family-of-the-marquis-de-miramon-1865/. <Date viewed.>

James Tissot executed his oil paintings with meticulous attention to detail, a characteristic of his temperament as well as his academic training in Paris, and he often painted a small preparatory study to work out his composition, palette, and use of light.

In fact, when the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut acquired a small painting in 1941, thought to be the work of an Impressionist painter, it later was recognized as a study for Tissot’s monumental 1865 family portrait, “The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children,” which had remained in the family until 2006. That year, it was acquired by the Musée d’Orsay, and the first time it was exhibited publicly since 1866 was with the blockbuster exhibition, Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity, which opened at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, from September 25, 2012 to January 20, 2013, traveled to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York from February 26 through May 27 and closed at the Art Institute of Chicago from June 26 to September 22, 2013.

Tissot’s study has been displayed by the Wadsworth Atheneum only since the museum’s recent renovation.

Study for the Family of the Marquis de Miramon (1865), by James Tissot. Oil on paper adhered to panel. 13.25 by 16.5 in. (33.7 by 42 cm). The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. (Photo copyright Lucy Paquette, 2016).

The portrait depicts René de Cassagne de Beaufort, marquis de Miramon (1835 – 1882) and his wife, née Thérèse Feuillant (1836 – 1912), posing with their first two children, Geneviève (1863 – 1924) and Léon (1861 – 1884) on the terrace of the château de Paulhac in Auvergne.

A comparison of the study with the finished painting gives us insight into Tissot’s working methods.

The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children (1865), by James Tissot. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. (Photo copyright Lucy Paquette, copyright 2015)

Tissot, then 29 years old, made the study with a general idea of the composition, the setting, the poses and costumes of his subjects, and his palette of greys, blues, and white enlivened with touches of red.

In the study, as in the completed portrait, the tall and elegant Marquise stands on the left of the canvas holding her daughter, Geneviève, and the Marquis is seated to their right in a casual pose.

The most noticeable difference in the finished portrait is that it is considerable lighter, brighter and more lively than the study, which is overall quite dark and stilted. Tissot achieved this effect partly through depicting more open sky through the trees, especially in the center of the painting and behind the heads of the Marquise and Geneviève. Their two faces, turned toward the viewer, are now closer together, providing a highly lit focal point.

The most noticeable difference in the finished portrait is that it is considerable lighter, brighter and more lively than the study, which is overall quite dark and stilted. Tissot achieved this effect partly through depicting more open sky through the trees, especially in the center of the painting and behind the heads of the Marquise and Geneviève. Their two faces, turned toward the viewer, are now closer together, providing a highly lit focal point.

And though the Marquise wears a black bolero in the finished portrait, rather than the blue bodice in the study, Geneviève’s figure is much brighter, and the Marquise’s magnificent silk skirt glows and shimmers with light. Tissot decided to extend the final canvas out to the left to accommodate the full sweep of her train.

The Marquis’ dark brown lounge suit in the study is replaced with a lighter grey one — and the red stockings Tissot initially considered for color were replaced by tall black leather riding boots. Color instead is provided by the red flower blossoms at the center of the composition, and the tasteful pink rose in the Marquis’ lapel. Tissot exchanged the Marquis’ broad blue tie for a more subtle spot of a darker blue underscoring his change from a three-quarters view of his subject to a full face portrait. The crisp white cuffs of the Marquis’ shirt provide another brightening touch in the final composition.

The Marquis’ dark brown lounge suit in the study is replaced with a lighter grey one — and the red stockings Tissot initially considered for color were replaced by tall black leather riding boots. Color instead is provided by the red flower blossoms at the center of the composition, and the tasteful pink rose in the Marquis’ lapel. Tissot exchanged the Marquis’ broad blue tie for a more subtle spot of a darker blue underscoring his change from a three-quarters view of his subject to a full face portrait. The crisp white cuffs of the Marquis’ shirt provide another brightening touch in the final composition.

As Tissot placed the Marquise, Geneviève, and the Marquis in his study, he clearly struggled with where to place the couple’s son, Léon. The study shows that he planned to paint Léon prominently in the center of the family, and initially, Léon stands in a studied pose reminiscent of an adult male in a formal eighteenth-century aristocratic portrait. However, this strikes a false note in a picture meant to be a modern, informal, English-style portrait of an affectionate family. Tissot also struggled with how to enliven the lower right corner of the composition. In the study, he fills that spot with a highly-patterned blanket and a bright red touch over a wooden ladder-back chair.

As Tissot placed the Marquise, Geneviève, and the Marquis in his study, he clearly struggled with where to place the couple’s son, Léon. The study shows that he planned to paint Léon prominently in the center of the family, and initially, Léon stands in a studied pose reminiscent of an adult male in a formal eighteenth-century aristocratic portrait. However, this strikes a false note in a picture meant to be a modern, informal, English-style portrait of an affectionate family. Tissot also struggled with how to enliven the lower right corner of the composition. In the study, he fills that spot with a highly-patterned blanket and a bright red touch over a wooden ladder-back chair.

In the finished painting, Tissot solved both artistic challenges by placing Léon in the lower right corner — in the chair. The red diced hose that Léon wears in the study have been exchanged for black diced hose, and behind him is a bright red plaid blanket. Further visual interest is provided in that corner of the picture by the ornate table cropped at the extreme right edge.

In the finished painting, Tissot solved both artistic challenges by placing Léon in the lower right corner — in the chair. The red diced hose that Léon wears in the study have been exchanged for black diced hose, and behind him is a bright red plaid blanket. Further visual interest is provided in that corner of the picture by the ornate table cropped at the extreme right edge.

The family’s large black dog has been relocated from its central position with Léon in the study to a more natural pose at Léon’s feet; Tissot used the dog, in the end, to enliven the central spot at the bottom of the canvas. In a decision that finally unifies the subjects in a pleasing composition, Tissot changed the Marquis’ pose so that his crossed legs lead the eye down his long black boots to the strong black diagonal of the reclining dog.

Léon’s pose is now more natural: he sits on his right leg while dangling his left one off the seat of the chair that he grasps with his hand. While his mother, sister and father gaze directly at the viewer, Léon is very much a little boy whose attention is elsewhere. The Marquis has now taken center place in the family group, and his figure is visually united with his wife’s by the halved pear, part of which is angled toward him while the knife handle is angled toward her.

The red touches that Tissot initially placed in the center and lower right of the composition still were used in the center and lower right in the finished portrait, but in different ways. And notice how the dog’s pink tongue provides the color between the two areas in both the study and the final painting.

Tissot’s study reveals the effort and creative decisions he made to produce one of his most polished and exquisite works.

His care with this composition, and his considerable technical skill in executing it, was reflected in all his work. The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their children was exhibited in Paris, at the Cercle de l’Union Artistique, in 1866, and entered him into the lucrative market for Society portraiture after a decade of living and learning in the French capitol. Although at least one critic did not like the overall grey palette of this picture, and felt that the portrayal of the little boy lacked impact, the Marquis de Miramon next commissioned Tissot to paint an individual portrait of his beautiful wife – and, two years later, a group portrait with eleven of his fellow club members that provided an even greater compositional challenge: The Circle of the Rue Royale.

The Marquis and the Marquise de Miramon and their Children (1865), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 69 11/16 by 85 7/16 in. (177 by 217 cm). Musée d’Orsay, Paris (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Related posts:

Ready and waiting: Tissot’s entrée, 1865

From Princess to Plutocrat: Tissot’s Patrons

Tissot in the new millenium: Museum Acquisitions

A spotlight on Tissot at the Met’s “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity”

Masculine Fashion, by James Tissot: Aristocrats (1865 – 1868)

James Tissot’s Fashion Plates (1864-1878): A Guest Post for Mimi Matthews by Lucy Paquette

© 2016 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

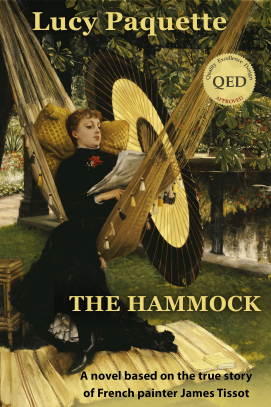

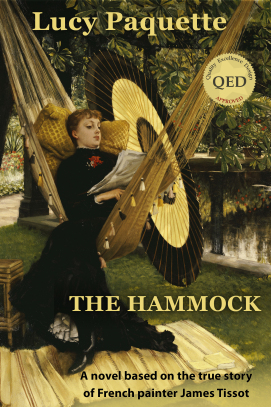

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.