To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “Celebrities & Millionaires Vie for Tissot’s Paintings in the 1990s.” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2014/10/17/celebrities-millionaires-vie-for-tissots-paintings-in-the-1990s/. <Date viewed.>

All auction prices listed are for general reader interest only, and are shown in this order: $ (USD)/£ (GBP). All prices listed are Hammer Price (the winning bid amount) unless noted as Premium, indicating that the figure quoted includes the Buyer’s Premium of an additional percentage charged by the auction house, as well as taxes.

Despite the exploding art prices for James Tissot’s oil paintings in the 1980s, there still were some bargains to be had in the early 1990s.

Going to business (Going to the City), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 17 by 7 in. (43.18 by 17.78 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

In Dobbs Ferry, New York, Suzanne McCormick (born 1936) and her husband, Edmund J. McCormick (1912 – 1988), a business executive, management consultant and philanthropist, collected American paintings before they began to buy 19th century British/Victorian paintings in 1976. Their collection was widely exhibited. After her husband’s death in 1988, Mrs. McCormick, a former pianist, sold a portion of the collection at Sotheby’s, New York in 1990. Tissot’s diminutive Going to Business (c. 1879), estimated at $250,000 to $300,000, sold for $ 180,000/£ 106,559.

.jpg) In 1991, the most colorful celebrity ever to own an oil painting by James Tissot purchased A Type of Beauty (1880). This portrait of Tissot’s young mistress and muse, Kathleen Newton (1854 – 1882), had sold at Sotheby’s, New York in early 1989 for $ 675,000/£ 385,560, but on October 25, 1991, it was purchased at Christie’s, London for only $ 273,760/£ 160,000 by rock star Freddie Mercury, of the band Queen. [A big thanks to the engaged reader who brought this fact to my attention via Twitter, then sent me documentation.] The painting was displayed in Mercury’s London home, Garden Lodge, a twenty-eight room Georgian mansion in Kensington amid a large garden surrounded by a high brick wall. Freddie Mercury died at 45 on November 24, 1991. In his will, he left Garden Lodge, worth £10 million, to his friend Mary Austin (b. 1951).

In 1991, the most colorful celebrity ever to own an oil painting by James Tissot purchased A Type of Beauty (1880). This portrait of Tissot’s young mistress and muse, Kathleen Newton (1854 – 1882), had sold at Sotheby’s, New York in early 1989 for $ 675,000/£ 385,560, but on October 25, 1991, it was purchased at Christie’s, London for only $ 273,760/£ 160,000 by rock star Freddie Mercury, of the band Queen. [A big thanks to the engaged reader who brought this fact to my attention via Twitter, then sent me documentation.] The painting was displayed in Mercury’s London home, Garden Lodge, a twenty-eight room Georgian mansion in Kensington amid a large garden surrounded by a high brick wall. Freddie Mercury died at 45 on November 24, 1991. In his will, he left Garden Lodge, worth £10 million, to his friend Mary Austin (b. 1951).

A Type of Beauty (Portrait of Kathleen Newton, 1880), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 23 by 18 in. (58.42 by 45.72 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

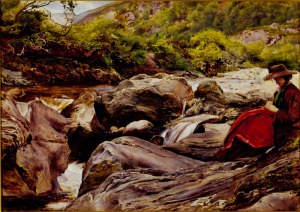

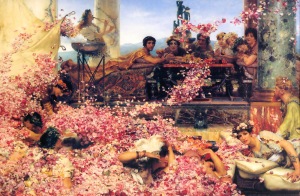

Tissot’s title can be explained by a painting by another painting of the era. For an exhibition called “Female Beauty,” The Graphic magazine commissioned paintings in 1880 by twelve artists including James Tissot, Frederic Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Marcus Stone. Alma-Tadema’s picture was titled Interrupted – A Type of Feminine Beauty. It was a portrait of his second wife, Laura Theresa Epps (1852 – 1909), seated in the sitting room of their London home, Townshend House, holding a copy of The Graphic.

Interestingly, The Graphic tried to sell Tissot’s A Type of Beauty in February, 1882 at Christie’s, London, but no one wanted it at the minimum bid of £ 67 4s!

In early 1993, Victorian art expert Christopher Wood (1941 – 2009) commented on the popularity of James Tissot’s oil paintings among Manhattan Society hostesses: “I can think of ten to twenty Tissots within a few blocks of each other in New York.”

So there was great excitement in New York that year on Wednesday, February 17 and Thursday, February 18, when Sotheby’s offered three major Tissot paintings, and Christie’s two.

The three paintings at Sotheby’s, from Tissot’s series of fifteen large-scale pictures called La Femme à Paris (The Parisian Woman) painted between 1883 and 1885, were being sold by Toronto collectors Joey and Toby Tanenbaum.

Joey Tanenbaum (born 1932), the son of Polish immigrants who made their fortune in steel fabrication, is Chairman and CEO of Jay-M Enterprises Ltd. and Jay-M Holdings and has built his fortune through real estate and hydroelectric power. He and his wife, Toby, bought Tissot oil paintings in the 1970s, when appreciation for Victorian painting was just beginning to grow. The Tanenbaums made a hobby of collecting rediscovered masterpieces of English and French academic painting, and it became nearly a full-time effort. By 1993, as their interest shifted to Old Master paintings, especially Spanish and Italian works of the 17th century, and antiquities, they were running out of ready cash to develop their collection. They put their three Tissot oil paintings up for sale at Sotheby’s, New York and hoped to beat the record price for a Tissot, $1,250,000/£ 797,295, set in 1989 at the same auction house for Reading the News (1874).

The Tanenbaums also said they sold the works rather than donate them to a museum because of recent decisions by Canada’s Cultural Properties Review Board.

The Tanenbaums’ three Femme à Paris paintings, each valued by Sotheby’s at $ 1.2-2 USD (£ 800,000-1.3 million), were:

La Mondaine (The Woman of Fashion), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 58 by 40 in. (147.32 by 101.60 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

‘La Mondaine’ – Woman of Fashion, sold for $ 1,800,000/£ 1,246,105.

Study for “Le Sphinx,” by James Tissot. Private Collection. (Photo: Wiki)

Study for ‘Le Sphinx’ – Woman in Interior, sold for $ 800,000/£ 553,824.

Sans Dot (Without Dowry), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 58 by 41 in. (147.32 by 104.14 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

‘Sans Dot’ – Without Dowry, sold for $ 800,000/£ 553,824.

The next day, at Christie’s, Tissot’s Jeune femme chantant à l’orgue (Young Woman Singing at the Organ), sold for $ 100,000/£ 69,180. L’Orpheline (Orphans), the better of Christie’s two Tissots, was expected to bring $ 600,000- 800,000 (£ 400,000- 530,000). It set a new record for a Tissot oil when sold for $ 2,700,000/£ 1,867,865 to art dealer David Mason, with MacConnal-Mason, a fourth generation gallery in St. James established in 1893. Mason buys for musical composer Andrew Lloyd Webber (b. 1948), who in the next decade would collect some of Tissot’s best work – at very high prices.

Beginning in 1993, American oil millionaire Fred Koch (b. 1933) sold his collection of Victorian paintings over several months. “Very few of the great paintings in that collection got past Andrew,” said one dealer. Lloyd Webber’s purchases from the Koch Collection include James Tissot’s Le banc de jardin (The Garden Bench), which he purchased in 1994 for $ 4,800,000/£ 3,035,093, a new record for the artist. [See James Tissot in the Andrew Lloyd Webber Collection.]

Quiet (c. 1881), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 13 by 9 in. (33.02 by 22.86 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

In early November, 1993, a small painting by Tissot appeared on the market. Quiet (c. 1881) originally was purchased by Richard Donkin, M.P. (1836 – 1919), an English shipowner who was elected Member of Parliament for the newly created constituency of Tynemouth in the 1885 general election. The small painting of Kathleen Newton and her niece, Lilian Hervey in the garden of Tissot’s house at 17 Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood, in north London, remained in the family, in perfect condition, until it was sold for $ 416,220/£ 280,000.

Chrysanthemums (c. 1874-76), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 46 by 30 in. (116.84 by 76.20 cm). Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. (Photo: Wikiart.org)

Chrysanthemums (c. 1874-76) was another Tissot oil sold from a long-held private collection as prices for the artist’s work surged in the 1990s. It originally was purchased by British cotton magnate, MP and contemporary art collector Edward Hermon (1822 – 1881) by 1877, the year his only daughter was married. In 1882, Hermon’s estate sold it at Christie’s, London to the prominent art dealership Arthur Tooth and Son. The painting next belonged to Surgeon-Major (the ranking surgeon of a regiment in the British Army) John Ewart Martin, South Africa and remained in a private collection of his descendants in South Africa until sold through Phillips, London, in December, 1993, to the Christopher Wood Gallery, London, for $ 372,125/£ 250,000. The painting was sold by that gallery to the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute at Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1994.

Mavourneen (Portrait of Kathleen Newton), 1877. Oil on canvas, 36 by 20 in. (91.44 by 50.80 cm). Private Collection. Photo courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library for use in “The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot,” © 2012 by Lucy Paquette

Tissot’s 1877 Mavourneen (Portrait of Kathleen Newton) had been in a private collection in Australia before it was purchased by Theodore Bruce, Adelaide, at Christie’s in 1984. By the next year, it was with the Owen Edgar Gallery, London. In 1995, it was sold to an American collector at Christie’s, New York for $ 2,300,000/£ 1,433,915. The painting, in which Mrs. Newton wears the same ensemble as she does in October (1877), was last exhibited at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington from November 28, 2006 through March 30, 2007. Kathleen Mavourneen was a popular love song of the time (“mavourneen” means “my darling”), as well as a play by William Travers, which enjoyed a revival at the Globe Theatre in July, 1876.

_by_James-Jacques-Joseph_Tissot.jpg)

A Winter’s Walk (Promenade dans la neige) (c. 1878), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 31.10 by 14.57 in. (79.00 by 37 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

The exquisite A Winter’s Walk (Promenade dans la neige) (c. 1878) has belonged to a number of private collectors over the decades, beginning with J.C. Haslam Esq., 32 Queen Anne Street, Cavendish Square, London, whose executors sold it at Christie’s in 1900 to London-based art dealer Arthur Tooth. By 1937, it was owned by Mrs. Bannister, and by 1956 by Henry (Harry) Talbot de Vere Clifton, Lytham Hall, Lancashire. Christie’s sold it once again in 1965, to Leger Galleries, London. It was in a private collection when it was sold at Sotheby’s, London in 1996, to another collector, for $619,160/£ 400,000.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Wall Street magnate John Langeloth Loeb (1902-1996) and his wife, Frances “Peter” Lehman Loeb (1907-1996), former New York City Commissioner to the United Nations, began to form what would become, over the next four decades, one of the greatest private art collections in the United States. The Loebs bought paintings from well-known New York dealers, especially Knoedler and Company, and at auctions in New York and abroad. They displayed them in their Park Avenue apartment, which they opened to curators as well as art historians and their students.

La cheminée/The Fireside (c. 1869), by James Tissot. 20 by 13 in. (50.80 by 33.02 cm). Private Collection. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

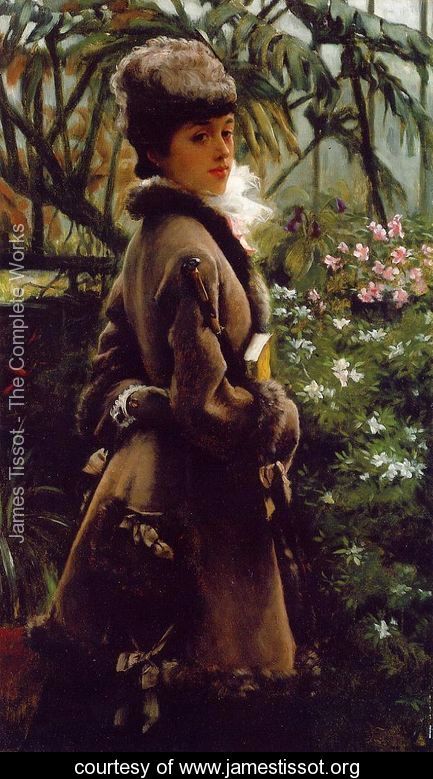

The Loebs acquired James Tissot’s La Cheminée/By the Fireside (c. 1869) from Knoedler and Company on January 31, 1955 and Dans la serre (In the Conservatory, 1867-69) from The Fine Arts Society, London on October 7, 1957. Both paintings almost certainly depict the interior of Tissot’s sumptuous villa on the avenue de l’impératrice (now avenue Foch) in Paris, which he moved into in early 1868.

Dans la serre (In the Conservatory, 1867-69, by James Tissot. 28 by 16 in. (71.12 by 40.64 cm). Private Collection. Courtesy http://www.jamestissot.org

When the Loeb Collection of twenty-nine French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, drawings and sculptures by twenty-one artists including Manet, Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Toulouse-Lautrec, Matisse, Gauguin, van Gogh and Picasso was sold at Christie’s, New York in 1997, it brought $92.7 million.

Dans la serre sold for $ 440,000/£ 270,986. American stockbroker Jerome Davis purchased La cheminée for $ 1,700,000/£ 1,046,991.

Tea (1872), by James Tissot. Oil on panel, 26 by 18 7/8 in. (66 by 47.9 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Photo: Wikipaintings.org)

Tea (1872) was one of Tissot’s eighteenth-century paintings calculated to appeal to British collectors once he had moved to London in mid-1871, following the Franco-Prussian War and its bloody aftermath, the Paris Commune. Tea was in a private collection in Rome, Italy in 1968. It was with Somerville & Simpson, Ltd., London, by 1979-81, when it was consigned to Mathiessen Fine Art Ltd., London. It was purchased from Mathiessen by Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, New York. Upon Mr. Wrightsman’s death in 1986, Mrs. Wrightsman (b. 1919) owned it until 1998, when she gifted it to the Met. Tea recently was put on display at the Met, in Gallery 815.

As of 1998, there were only eighty oil paintings by James Tissot in public art collections worldwide: twenty-five in the U.K., two in the Republic of Ireland, twenty in France, twenty-one in the continental U.S. and one in Puerto Rico, five in Canada, one in Switzerland, one in India, two in Australia, and two in New Zealand.

Still on Top (c. 1874), by James Tissot. Oil on canvas, 88 by 54 cm. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, New Zealand. (Photo: Wikimedia.org)

Tissot’s Still on Top (c. 1874), is in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki in New Zealand, the gift of British industrialist and politician Viscount Leverhulme (1851 – 1925) in 1921, when it was worth approximately £ 500. Still on Top depicts two women and an elderly male servant wearing a red liberty cap, a revolutionary symbol in France. It had only been three years since Tissot had fled Paris – under some suspicion – during the French government’s suppression of the radical Paris Commune. It’s really rather daring for an apparent French political refugee of the time, remaking his career in England: as the three figures raise the flags, which is on top?

Painted in Tissot’s extensive garden at his home in St. John’s Wood, London, the picture is similar to his Preparing for the gala, which came up for auction at Sotheby’s, New York in May, 1996. Preparing for the Gala sold for $1,650,000/£ 1,090,188.

On the morning of Sunday, August 9, 1998, the slightly larger Still on Top, worth $3.5 million USD, was stolen from the Auckland Art Gallery by a 48-year-old man with a shotgun who then asked $260,000 ransom from the Auckland Art Gallery. The painting was recovered under a bed at the home the man rented in Waikaretu, south of Port Waikato, on August 17. Restoration of the picture, which had been terribly damaged, began in February 1999. [For the full story of the robbery – including surveillance video – and the repairs to Still on Top, click here.]

Later that year, from September 22 to November 28, 1999, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, held the first Tissot retrospective in the U.S. since 1968: “James Tissot: Victorian Life/Modern Love.” The exhibition featured approximately 40 paintings, 40 prints and 20 watercolors selected from public and private collections in North America, Europe and Australia, including works from the Tate Gallery in London, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. On display for the first time in the U.S. was Tissot’s The Hammock (1879), reportedly owned at that time by American stockbroker Jerome Davis of Greenwich, Connecticut.

The exhibition traveled to the Musée du Québec, Québec City, from December 15, 1999 to March 12, 2000 and to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo from March 24 to July 2, 2000.

© 2014 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related posts:

James Tissot oils at auction: Seven favorites

Kathleen Newton by James Tissot: eight auctioned oil paintings

Tissot’s La Femme à Paris series

James Tissot and the Revival of Victorian Art in the 1960s

If only we’d bought James Tissot’s paintings in the 1970s!

James Tissot’s popularity boom in the 1980s

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you can download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you can download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9). See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.