To cite this article: Paquette, Lucy. “What happens at the Tissot Symposium…stays at the Tissot Symposium?” The Hammock. https://thehammocknovel.wordpress.com/2020/02/13/what-happens-at-the-tissot-symposium-stays-at-the-tissot-symposium/. <Date viewed.>

Melissa Buron and Lucy Paquette

When I visited James Tissot: Fashion and Faith at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco with my husband in November, 2019, curator Melissa E. Buron spent the morning showing us through the galleries.

I’d be lying if I said I sedately strolled through these rooms, each spilling into another, all gleaming with Tissot paintings – of course I darted, mid-sentence, from picture to picture, many of which were on loan from private collections or from institutions I have not yet visited. I recall squealing rather indecorously. We talked nonstop, sharing our thoughts and experiences. Melissa and I have a kindred…well, obsession with Tissot. Over lunch, she asked me to present at the exhibition’s closing symposium, February 8-9, 2020.

Cassandra Sciortino, Melissa Buron and Peter Trippi discussing Tissot during Scholar’s Hours in the Exhibition galleries

It was an honor to be invited to present at this symposium and to meet interesting colleagues working across a wide range of subjects related to Tissot studies.

I made new friends and enjoyed the collegial sharing of information within a larger community of “Tissotistes.”

It was 48 hours of non-stop Tissot immersion, which may sound fairly deranged, but akin to spending a whirlwind weekend at Disneyland: magical, hectic, and focused on an outsized character.

My presentation was one of eight, four on Saturday and four on Sunday, before an audience of museum members, interested professionals, and the public, in the Legion of Honor’s elegant Gunn Theater:

February 8, 2020, Part I: “Fashion”

“Behind-the-Scenes: Revealing Tissot’s Paint Technique,” by Sarah Kleiner, Associate Paintings Conservator, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

“Behind-the-Scenes: Revealing Tissot’s Paint Technique,” by Sarah Kleiner, Associate Paintings Conservator, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

“Chicks with Guns: Tissot’s The Crack Shot and Women’s Relationship to Firearms,” by Nancy Rose Marshall, Professor of Art History, University of Wisconsin-Madison

“James Tissot and ‘the little class’ of the Belle Époque,” by Lucy Paquette, independent art historian

“‘The Impresario:’ Degas – or Tissot?” by Anthea Callen, a frequent expert on BBC’s Fake or Fortune?, Professor Emeritus of Art, Australian National University, Canberra, and Professor Emeritus of Visual Culture, University of Nottingham, U.K.

February 9, 2020, Part II: “Faith”

The Legion of Honor’s lovely Gunn Theater

“Solving the mysteries of Kathleen Newton’s life: New findings and facts,” by Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, independent curator and art historian

“Scientists and Spiritualists Imaging Ghosts at the fin de siècle,” by Serena Keshavjee, Professor of Art and Cultural Studies, University of Winnipeg

“Tissot’s travelogue from the Holy Land,” by Paul Perrin, Curator of Paintings, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

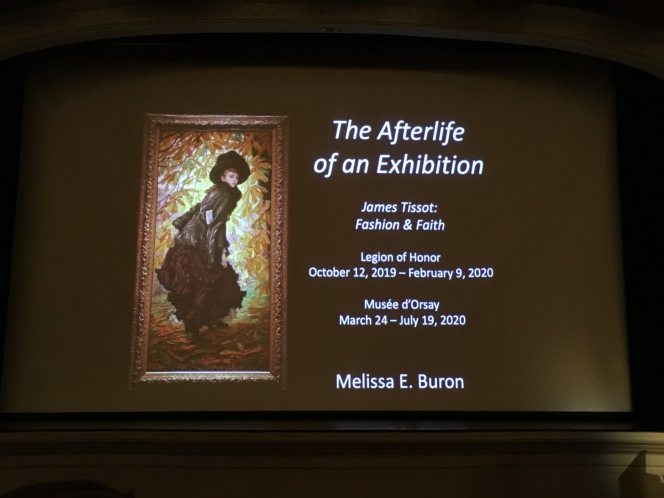

“James Tissot: The Afterlife of an Exhibition,” by Melissa Buron, Director, Art Division, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

The presentations were videotaped, and the Legion of Honor has posted links on YouTube: February 8, 2020, Part I: “Fashion” and February 9, 2020, Part II: “Faith”. You can view mine, “James Tissot and ‘the little class’ of the Belle Époque,” (on the link to February 8, from 1:16 to 1:46), as well as the others in these two videos, such as:

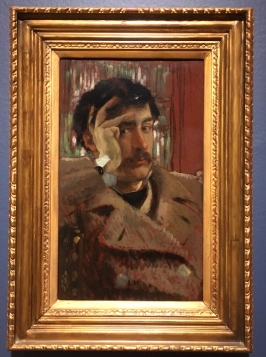

- Sarah Kleiner’s fascinating analysis, from results of a two-year international collaboration, of Tissot’s techniques and materials, and the discovery that his oils, Self-Portrait (c. 1865, above left, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) and Melancholy (c. 1869, above right, private collection) were painted on two halves of a single panel of mahogany, whose horizontal grain is shown to align by X-radiographs. Such research is useful when dating paintings and considering attribution.

- Anthea Callen’s meticulous exploration of a theory, originally asserted by Richard Thomson in 1988, that the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco’s oil study, The Impresario (c. 1877), is not by Edgar Degas, but James Tissot. I was sold early in her talk, when she noted that Degas did not do the type of preparatory study in oil that was so characteristic of Tissot’s work. But a side-by-side comparison of The Impresario and Tissot’s paintings, Evening (1878) and The Political Woman (c. 1883-85), was even more convincing.

PowerPoint slide by Anthea Callen juxtaposing The Impresario (center, currently attributed to Edgar Degas) with James Tissot’s Evening (left) and The Political Woman (right). The poses of the three male figures are strikingly similar.

-

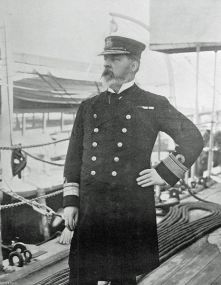

Rear-Admiral H. Bury Palliser at age 56, in Navy & Army Illustrated May 15th 1896. http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Henry_St._Leger_Bury_Palliser

Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz’s exciting archival research on Kathleen Ashburnham Kelly Newton’s life, and her identification of the Naval officer who seduced her on her journey during August and September of 1870, when she was 16 years old, to marry older widower Dr. Isaac Newton in northwest India as Henry St. Leger Bury Palliser (1839–1907). Directly after the wedding, Kathleen admitted her improper relations with Palliser and found herself alone, penniless and pregnant, asking the doctor to pay for her journey back to England.

[Palliser, often referred to as “Captain Palliser” in relation to Kathleen Newton, was appointed a Commander in the Royal Navy in 1869. He would have been 31 when he met Kathleen Kelly, who was motherless and fresh out of Gumley House Convent School in Isleworth.]

Dr. Newton divorced Kathleen, and she had her baby (her daughter, Violet Newton, December 20, 1871–December 28, 1933) at her father’s house in Conisbrough, Yorkshire, but she soon moved to London, living with her older sister around the corner from James Tissot’s St. John’s Wood villa.

-

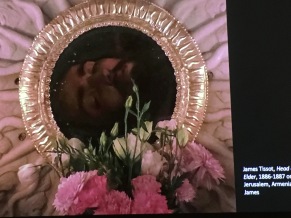

Head of Saint James the Elder, 1886-1889, Jerusalem, Armenian Cathedral of Saint James. PowerPoint slide by Paul Perrin.

Paul Perrin’s amazing discovery of an unknown, 60-page handwritten manuscript by James Tissot – a travelogue of his time in the Holy Land, conducting research for his Bible illustrations. A letter from a publisher in New York indicates that Tissot had plans, which never materialized, to publish his manuscript as a travel epic and guide. Paul announced his even more amazing discovery that Tissot’s travelogue led him to a formerly unattributed painting by Tissot, at The Cathedral of Saint James, a 12th-century Armenian church in Jerusalem.

PowerPoint slide by Melissa Buron

- Melissa’s emotional adieu to the exhibition, now on its way to Paris, where it will be on view, with some variation, from March 23 through July 19, 2020. She calls James Tissot “the most interesting artist in the 19th century that you’ve never heard of.”

But it’s clear that this is changing.

In 2009, when I began researching James Tissot for my book, The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, there was little popular interest in him, and only a handful of scholars were dedicated to researching his life and work. On Twitter, that barometer of cultural awareness, I was alone in posting images of James Tissot’s wonderful paintings after publishing my novel in 2012 and embarking on my blog, The Hammock, to share more about him.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née Thérèse Feuillant (1866), by James Tissot. Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In 2013, Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity, curated by Gloria Groome, now Chair of European Painting and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, was a revelation as an unheralded mini-exhibition of James Tissot’s most spectacular paintings. In New York, at the Met, people (including me) vied for a position close enough to examine the Musée d’Orsay’s relatively new acquisitions, Portrait of the Marquis and Marquise of Miramon and their children and The Circle of the Rue Royale, clearly reluctant to step away from these poignant, exquisite glimpses of a lost world. And yet, Tissot’s reputation was such that a reviewer for The New York Times disparaged the gorgeous Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon as “zealously detailed,” Advertising for this blockbuster exhibition barely mentioned James Tissot – why, when he had no name recognition?

Across the country, Melissa Buron reacted with the same frustration that James Tissot and his work were not receiving their full due when she witnessed the artist’s work overshadowed by his more famous countrymen. She began her efforts towards the Legion of Honor retrospective, and is on the vanguard of a new era of fascination with James Tissot, welcoming new voices and directions in research. Melissa, along with fellow curators Paul Perrin and Marine Kisiel at the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie, Paris, and Cyrille Sciama, Director of Musée des impressionnismes Giverny, is bringing Tissot’s work to a wider public and redefining his place in the history of 19th century art.

Tissot scholars indulging in Paul Perrin’s Instagram sensation, #tissotpose

And now, with that new fascination combined with the energy of social media, rather than a few art historians viewing Tissot research as an exclusive domain, Tissot scholarship encompasses everything from a stylish new documentary film on his life and work, James Tissot, The Ambiguous Figure of Modernity, as France reclaims its former superstar, to stunning recent discoveries of Tissot’s “lost” art, biographical information, and important documents, photographs, and letters that have been “hiding in plain sight,” to Instagram crazes like Paul Perrin’s #tissotpose – and yes, my blog on James Tissot’s life, art, associates and times.

Importantly, what all this accomplishes is to make James Tissot accessible. And what that accomplishes is to make him popular, when one of the greatest frustrations of Tissot scholars is that he is so much less well-known than his peers such as Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, or the biggest marketing draw, “The Impressionists.” As museum professionals know, a popular artist makes for a well-attended exhibition, in which efforts to engage, inform, and delight a broader audience can have a much greater opportunity for success and satisfaction.

All of this would be immensely rewarding to James Tissot, who believed in himself and his art enough to decline the invitation to exhibit with the Impressionists, who saw his reputation obscured by theirs but who continued to pursue his own idiosyncratic path, knowing that his work was special, significant – and unforgettable.

Special thanks to the following staff at the Legion of Honor:

Lexi Paulson

Administrative Coordinator to the Director, Art Division

Isabella Holland

Curatorial Assistant, European Paintings

Danny Cesena

Audio Visual Technical Coordinator

© 2020 by Lucy Paquette. All rights reserved.

The articles published on this blog are copyrighted by Lucy Paquette. An article or any portion of it may not be reproduced in any medium or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, without the author’s permission. You are welcome to cite or quote from an article provided you give full acknowledgement to the author.

Related posts:

James Tissot: Fashion & Faith, a retrospective at the Legion of Honor

James Tissot, the painter art critics still love to hate: a retrospective review round-up

James Tissot, the painter art critics love to hate

A spotlight on Tissot at the Met’s “Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity”

If you do not have a Kindle e-reader, you may download free Kindle reading apps for PCs, Smartphones, tablets, and the Kindle Cloud Reader to read The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot. Read reviews.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot, brings Tissot’s world from 1870 to 1879 alive in a story of war, art, Society glamour, love, scandal, and tragedy.

Illustrated with 17 stunning, high-resolution fine art images in full color

Courtesy of The Bridgeman Art Library

(295 pages; ISBN (ePub): 978-0-615-68267-9).

See http://www.amazon.com/dp/B009P5RYVE.

The Hammock: A novel based on the true story of French painter James Tissot is now available as a print book – a paperback edition with an elegant and distinctive cover by the New York-based graphic designer for television and film, Emilie Misset.